http://www.westcorp.net/kelowna-downtown-hotel.php

Land and housing issues have been in the news quite a bit lately. Housing affordability was a major issue in the recent provincial election. In the February budget, the provincial government extended the speculation tax beyond Vancouver to other hot property markets, including Kelowna and West Kelowna. The introduction of the tax in Vancouver likely drove investment to other parts of the province, including Kelowna. Its application to Kelowna has those who benefit from that investment inflow concerned (Kelowna mayor says B.C.’s speculation tax could have ‘dire unintended consequences’). Here in the Okangan, local government land use decisions have also made the news. Kelowna city council recently approved a new tower that city staff recommended against (Kelowna city council approves $200 million, 33 story hotel in downtown core). The community of Peachland amended its official community plan (OCP) to allow a development that exceeded the height restrictions in place at the time (Council gives Peachland development another green light). The property market is hot, vacancy rates are low, land owners are making lots of money, and those without the means are struggling to find rental accommodation or buy into the housing market.

The economist David Ricardo (1772-1823) is credited with the Law of Rent. Ricardo observed that the maximum a tenant would pay to rent a parcel of land depended on what they could earn by renting the land, relative to renting another parcel. It does not depend on what they actually earn by renting the land. If there are no limits on what an owner or tenant can use their land for, then it will (eventually) be put to that use which results in the highest earnings. That use will depend on the options available, options that depend on restrictions like zoning, OCPs, environmental requirements, the Agricultural Land Reserve, etc.

The economist David Ricardo (1772-1823) is credited with the Law of Rent. Ricardo observed that the maximum a tenant would pay to rent a parcel of land depended on what they could earn by renting the land, relative to renting another parcel. It does not depend on what they actually earn by renting the land. If there are no limits on what an owner or tenant can use their land for, then it will (eventually) be put to that use which results in the highest earnings. That use will depend on the options available, options that depend on restrictions like zoning, OCPs, environmental requirements, the Agricultural Land Reserve, etc.

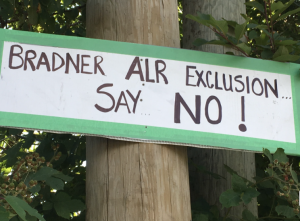

http://www.bradnerbarker.com/news/no-alr-exclusions-rally-planned

If the restrictions are permanent, then land will be priced based on what can be earned from permitted uses. However, if the restrictions are ‘flexible’, then there will be people willing to gamble on the restriction being lifted, and pay based on what they expect to earn. This is one source of speculation. ALR exclusions and local governments allowing variances from the OCP and zoning rules help drive speculation. Another source of speculation is gambling on growth in demand – population and economic growth. In both cases, as noted by Ricardo, the land owner is the ‘residual claimant’. When housing markets are competitive, and the markets for those things that go into building houses are competitive, renters, buyers, carpenters, etc. will make a ‘fair return’, while the ‘excess return’ is captured by the land owner. Booming property markets are primarily a benefit for property owners, and don’t do that much to benefit others.

http://www.mascotmine.com/index.html

The idea within Ricardo’s law of rent has been applied in other economic analyses. In particular, it has found application within resource economics. Resource rent is the name given to the profit that a resource owner earns after a fair return is paid against the cost of developing the resource and bringing it to market. Since the resource owner didn’t create the resource, is it fair that they get to keep the resource rent? There is broad agreement that they should not keep all of it. That is why we charge royalties on mineral resources and stumpage on timber resources. The province collects a share of the profit in excess of a fair return to the resource owner, on behalf of the citizens of the province (e.g. BC Oil and Gas Royalty Handbook). There is of course always the question of what share the province should collect, with the resource sector typically arguing that if royalties are raised, the sector will shrink.

What is the difference between a natural resource like zinc and land? Zinc is a finite, nonrenewable resource whose value depends on global markets. The demand in those markets is based on technologies that use zinc, and has nothing to do with how much zinc there is in the world. The price does depend on how much there is, and the profits that owners of zinc deposits earn depends on that price. Land in Kelowna is a finite, nonrenewable resource whose value depends on global markets. The demand in those markets is based on income levels and preferences for the natural and human created amenities in the area, and has nothing to do with how much land there is in Kelowna. However, the price does, and the profits that land owners can earn depends on that price. Like zinc, land owners do not create the value of their location. They may add value by developing something on the land, but the value of the bare land is a consequence of a larger market. Should we be collecting royalties on land development in the same way we do on natural resources?

What is the difference between a natural resource like zinc and land? Zinc is a finite, nonrenewable resource whose value depends on global markets. The demand in those markets is based on technologies that use zinc, and has nothing to do with how much zinc there is in the world. The price does depend on how much there is, and the profits that owners of zinc deposits earn depends on that price. Land in Kelowna is a finite, nonrenewable resource whose value depends on global markets. The demand in those markets is based on income levels and preferences for the natural and human created amenities in the area, and has nothing to do with how much land there is in Kelowna. However, the price does, and the profits that land owners can earn depends on that price. Like zinc, land owners do not create the value of their location. They may add value by developing something on the land, but the value of the bare land is a consequence of a larger market. Should we be collecting royalties on land development in the same way we do on natural resources?

http://idolza.com/

My late father and I would talk about these issues, and several times he told me about how the Netherlands managed land development. During his time there, land development was largely managed by national and local governments, who expropriated land, serviced it, and then either built on it or sold it for development. The government, on behalf of the citizenry, captured much of the value of changing land use. This was very different from the North American approach, where land use changes, largely approvals by local government, create windfall profits for land owners. However, over the last couple of decades things have changed substantially in the Netherlands. Court rulings in several nations, based on the European Convention on Human Rights, have challenged expropriation laws as contraventions of the right for individuals to the peaceful enjoyment of their possessions (Groetelaers, 2006). The Netherlands, and other European nations that had similar land development policies, are sorting out a new balance between private and public involvement in land development. This rebalancing towards the private market has driven up housing prices and enabled land owners to capture some profits that previously were enjoyed by the larger community.

While indigenous perspectives do not seem to see any land as unused, the colonizing perspective in North America and elsewhere that western society has expanded into proceeded for a long time by granting vacant land to settlers. We have largely run out of vacant (stolen?) land to hand out to people without land. Until we start colonizing other worlds, we are going to have to figure out how to manage the development of land in a way that balances the rights of land owners with the fundamental human need for housing, the community need for public amenities, and the needs of the environment (of the land) we all live within. Do we have that balance right?

While indigenous perspectives do not seem to see any land as unused, the colonizing perspective in North America and elsewhere that western society has expanded into proceeded for a long time by granting vacant land to settlers. We have largely run out of vacant (stolen?) land to hand out to people without land. Until we start colonizing other worlds, we are going to have to figure out how to manage the development of land in a way that balances the rights of land owners with the fundamental human need for housing, the community need for public amenities, and the needs of the environment (of the land) we all live within. Do we have that balance right?

Follow

Follow

Hi John, a very interesting topic and a perspective that I’d not come across before. We certainly are in trouble when we allow developers to do our urban planning for us – the evidence is all around us in urban sprawl. And this is a good reason we should not ignore local politics, and should make sure that developers (land speculators) and their supporters do not dominate our municipal councils.