There is so much history here. You literally cannot walk fifty feet without tripping over ancient ruins.

I took a field trip out to Caerleon today. Prior to reading Rick Steves, I mostly knew Caerleon as the supposed location of King Arthur’s winter court. This association probably stems from the still-visible Roman amphitheater just outside of town, which vaguely resembles, by some stretch of the imagination, a huge round table. (Caerleon styles itself as “the real Camelot,” which I’m not sure is strictly accurate—most Arthurian sources I’ve read name it as one of several seasonal courts.)

My destination today was the National Roman Legion Museum. Leaving aside the usual adventures in navigation that are my trademark, I arrived in Caerleon at about noon. (I meant to arrive when it opened at ten. You can fill in the gaps.)

Google describes Caerleon as a suburb of Newport, so I suppose I was expecting something in the vein of Generic UK Suburbia. Instead, I found a beautiful medieval town of narrow streets, weathered stone buildings, and rolling hills and fields, perched on a rise above the muddy River Usk.

The museum certainly looks the part:

Like many UK museums and historic sites, admission is free (the Brits are so much more civilized than we are).

In any case, I shouldn’t have fretted about timing; while lovely and thorough, the museum is only one room, and even a hard-core Roman enthusiast could get through it in an hour or two (I managed to make it three, mainly because I read every single plaque in every single case and then read all the extra pamphlets on the table and also watched the entire video playing in a loop on the TV screen in one corner).

There’s also an outdoor area with a Roman-style garden and a couple of reconstructed Roman buildings, although it was raining pretty hard and none of the buildings were open, so I didn’t spend much time out there.

To the best of my knowledge, the history of the Romans in Caerleon goes something like this:

In the second century AD, one of the Roman emperors—Claudius?—conquered Britain. Many of the Celtic tribes surrendered quickly, but the Silures (South Wales) and the Ordovices (North Wales) put up a fight and dealt an embarrassing defeat to the first Roman legion sent after them. Boudicca and the Icenii (another long story) distracted the Romans for a while and gave Wales about ten years’ grace, but eventually the Romans were back, and this time, in a bold move, they marched deep into the Silures’ territory and rapidly erected a fort on the banks of the River Usk. This fort was Isca, which would eventually become Caerleon. Initially, Isca consisted of earthworks and a timber palisade, but after the Silures and Ordovices were defeated, it was rebuilt in stone. It was home to one of only three permanently-stationed legions in Britain, the other two being Eboracum (York) and Deva (Chester). A sizable Roman town grew up around the fort. This included the amphitheater, about which you will hear later.

(A side note: In writing this post, all I could remember was that the Silures were in the south and the other tribe started with an O. I typed “Silures and O” into the Google search box. According to Autofill, the other tribe was called “On Toast.” Silures On Toast is evidently a type of red ale.)

Some highlights from the cases include:

Luggage tags. Because yes, Romans had trouble telling their luggage apart, too. (Although I’m not sure if these solved the problem, since everyone seemed to be named Julius.)

These made me think of Dad for some reason.

(Seriously. Julius. Like, all of them. There were eight gravestones on display on one wall. Five Juliuses, two Julias and a Marcella.)

This dagger is very cool, but check out the sheath. Zoom in on that silverwork detail.

One thing that struck me is how differently things age. You look at the dagger and you say, yes, that came out of a 1,800-year-old grave.

But then you look at something else, like glassware, and you’re like, didn’t I see that on Nana’s coffee table last week?

Metal ages terribly. Glass doesn’t age at all.

People don’t age very well, either:

As the plaque puts it, a backhoe is not a very good excavation tool. This Roman coffin turned up when the University of Swansea (I think?) was expanding its campus. Imagine the driver’s surprise.

Analysis of the skeleton showed that this Roman grew up in the area and died around the age of 40. The stone coffin demonstrates that he died wealthy. (In the words of the plaque, which was obviously written by a person after my own heart: “Local Boy Makes Good.”)

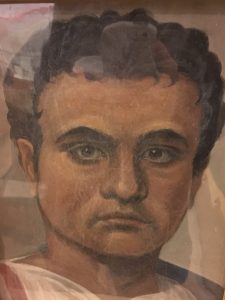

Here’s a painting of the coffin’s occupant, done in the Roman style with Roman materials based on a modern facial reconstruction:

Burials became common in the 200s-300s (probably with the arrival of Christianity?), but prior to that, cremations were the norm. This is an interesting display that recreates the context in which this lead pot of human ashes was originally buried:

The interesting bit is—and in this photo you can barely see it because of the glare off the glass—there’s a pipe that runs from the surface down into the pot of ashes.

This was for libations. Family members of the deceased would pour milk, honey or wine down the pipe and into the pot.

Another highlight was this mosaic from the floor of the legion headquarters:

(Just try tracing that labyrinth design with your eyes. It is much more complex than it looks.)

This is a reconstruction of a legionary’s full gear:

And at last I have an answer to a question that has caused me existential bafflement my whole life: “How did Roman helmets stay on their heads?”

Although Roman legion helmets appear to break physics, especially with the addition of a heavy horsehair plume, there’s a secret. The secret—if you look closely—is a strap that fastens to the underside of the back brim and ties under the chin.

Okay, enough geeking out about the minutiae of armor.

So I finished the museum and was not yet ready to tackle the question of how to get home, and since it was no longer raining, I decided to take a stroll. I meandered up Museum Street and then down a sidewalk out of town, where I found a bike and foot trail. Despite the fog, or perhaps because of it, there was something very picturesque about the rolling fields and hills and bare trees. Then what should I accidentally spot (note: there was very little signage), but:

Take a nice close look at the thing lurking in the grass on the right side of the hedge.

This is how I accidentally found the Roman amphitheater/the Round Table, which has free admission and…

…was closed for inclement weather.

This is not inclement weather. This is Welsh weather.

I did manage to find my way back to my bus stop at the edge of town, and while waiting for the bus, I happened to turn around and see this:

This is the Hanbury Arms on the bank of the River Usk. Take a nice look at the thing growing out of its corner.

Yes, ladies and gentlemen. This is a pub in a 16th-century coaching inn with an honest-to-God 13th-century CASTLE TOWER just kind of growing out of the corner.

Also, according to the internet, Tennyson came to Caerleon for a research trip (ahh, the grand tradition of writers on research trips) and stayed here, where he wrote part of The Idylls of the King. His room has been left exactly how it was since then.

I wonder if they’ll do that for my room at Tintagel…