And now, the post you’ve all been waiting for…

I made it to Tintagel Castle today. This is the castle I have wanted to visit since my freshman year of high school when I began writing The Sword in the Circle. After five years of on-and-off internet research, the real thing felt both very familiar and very foreign.

Here’s the approach:

From Tintagel Village, you walk down a footpath (there’s a vehicle path, too, but it’s only for English Heritage maintenance vehicles and ATVs). In this photo, you can just see the cafe (right) and visitor center with small gift shop and one-room exhibit (left, but hidden by the hill). These used to be, respectively, the headquarters of a slate mine and the cottage of the caretaker (Florence Nightingale Roberts).

The ticket office is not, as you would expect, in the visitors’ center. You actually walk along a boardwalk halfway between beach and clifftop to reach an intersection of three stairways, where there’s a ticket kiosk:

(I took most of my images in the form of videos today, and those are too big to upload, so there are odd gaps in my photo collection, including any image that does justice to the sheer number of stairs at Tintagel. Not for nothing is there a T-shirt in the gift shop that says “Tintagel Castle: I Conquered The Stairs.”)

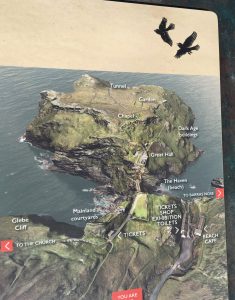

After buying your ticket, you can either go across a short wooden footbridge to the island or up the cliffs to the lower and upper wards. There is absolutely no way to explain this without referring to the map. Ignore the blurry labels. They’re misleading anyway:

So the ruins are spread across the mainland and that island, which is technically a headland because it’s connected by a narrow, impassable strip of rocky ground. There’s the short wooden bridge from the base of the mainland stairs to the base of the island stairs, but either way, it’s a lot of stairs. (Even the bridge is shallowly stepped.)

Here’s an artist’s rendition of Tintagel Castle in the early 1300s.

Quick crash course in Tintagel history:

Once upon a time, the island was connected to the mainland via a natural stone causeway (seen in the artist’s rendition: everything from the corner of that square ward to just beyond the tower). The ‘island,’ which was at that point a headland, has been occupied at least since late Roman times, according to shards of pottery found in archaeological digs.

During the Dark Ages, there was a settlement of at least a hundred buildings on the island/headland. It was likely a seasonal court for the king of Dumnonia, a powerful kingdom that encompassed Cornwall, Devon, and Somerset(?). It had trading ties to the Mediterranean—importing wine, olive oil, and other Roman goods.

The site’s associations with Arthurian Legend began in the 1100s with Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Brittaniae, or History of the Kings of Britain, a pseudo-historical account that includes Arthur’s conception at Tintagel Castle.

Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall, the younger brother of Henry III of England, built the current Tintagel Castle in the 1230s to capitalize on the Arthurian association and align himself with the historical rulers of Cornwall. (Tintagel was also the site of the popular Tristan and Iseult romance, and he built several settings from that legend, such as the walled garden in which the lovers supposedly met). Most of the current ruins date from this time. He had many castles throughout Cornwall, and Tintagel was occupied for only a few decades before falling into disrepair. After his death, it was maintained only by a constable and a few paid retainers. It was used briefly as a jail in the 1300s, and at one point there may have been a monastery on the island.

The site was already in disrepair shortly after Richard’s death, and with the collapse of the natural stone causeway in the 1500s, the site was abandoned altogether except for rabbits and sheep.

Interest revived, of course, with the Romantic poets and the Victorians in the 19th century, particularly following the publication of Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, which introduced the concept of Merlin’s Cave, the sea cave at the foot of one of the cliffs. (The cave was inaccessible today because of storm damage to that set of stairs.)

Recently, there’s been controversy over the Disnification of Tintagel:

But I’m actually not complaining. This statue is cool. He’s called Gallos (Cornish for ‘power’). He stands at the far end of the island.

There’s lots (and lots and lots) of cliffs:

And here’s part of Earl Richard’s castle on the island. The place was so naturally defensible that the walls really weren’t all that high or thick. Besides, this was a showpiece, not necessarily a siege-ready castle.

Throughout Tintagel’s history, the sheltered cove has been an import/export center. How you’d get a ship in there, I don’t know. The cove may be sheltered, but boy is it rocky.

Here’s the “Iron Gate” (so-called because it probably at some point had an iron gate in it).

It was the main loading/unloading gate for goods brought to the castle by sea, but I don’t understand how. It’s halfway up an almost-sheer hill, with a skinny winding path down to a ledge still fifteen feet above the water, and another skinny winding path up to the castle. Hauling heavy barrels up and down that would have been really fun.

Here’s that rocky harbor from high up on the island.

(Doesn’t that turquoise water look almost tropical?)

Here’s the view from the island back across most of the island and mainland ruins. You can see Earl Richard’s forecourt below-ish, and across the gap, the upper and lower wards on the mainland cliff. Over on the left are the visitor center and cafe.

(The lighting cooperated at no point during my visit. There was always glare somewhere and shadow somewhere else.)

And here is the lower ward as seen from the upper one.

In my research, I thought that lower and upper just referred to their proximity to the ocean, but no, the upper ward is literally about twenty feet above the lower ward, perched on a rock. It was originally wider, but part of the cliff sloughed off in the 1200s, taking a section of wall with it. Now it’s long and skinny, with a fifteen-foot wall cupping one end and the foundations of earlier or later buildings buried in the grass throughout. Supposedly there was a medieval loo projecting over the cliff somewhere, but I never found it.

I feel that medieval loos are a good note to end on. Sorry for the mediocre photos. Mostly what I took were short narrated video clips.