You can’t be a travel blogger visiting the Netherlands without doing a post about the windmills.

I was going to do a series of photos walking you through all the mechanics of the windmills at Kinderdijk, until I realized I don’t really understand the mechanics of anything invented more recently than the wheel.

So here, have some windmills.

This is the one in Leiden. You can just see how the cap that the blades are attached to rotates so that no matter which direction the wind blows from, you can always catch it. Windmills often have names, like “de Oranjeboom” (the Orange Tree) or “de Sleutels” (the Keys). This one is a reconstruction of de Valk (the Falcon).

This is another one in Leiden, a much more archaic design from before those rotating hubs were invented. You can’t really tell from this picture, but the entire mill is built on a rotating hub:

Here’s a windmill built in 1743.

As for what the windmills actually did:

Much of the Netherlands is below sea level. The country was once mostly lakes and marsh. Windmills were introduced in the early middle ages, probably by crusaders returning from the Middle East, but came into common use in the Netherlands in the 16th and 17th centuries.

What windmills do is pump water from a lower channel into a higher channel (called, to the amusement of adolescents everywhere, a “bosom”) to prevent the lower channel from flooding.

(And no, I don’t understand where the floodwater is supposed to go once it’s in the bosom.)

At one time there were thousands of windmills keeping the Netherlands dry. Now there are only a few hundred. Many of these are at Kinderdijk, a UNESCO World Heritage site, seen below:

(I managed to snap this picture at probably the only time that there wasn’t a lightning bolt touching the horizon during our visit. You can imagine how fun Dutch thunderstorms are, considering that the entire Netherlands is one giant open field.)

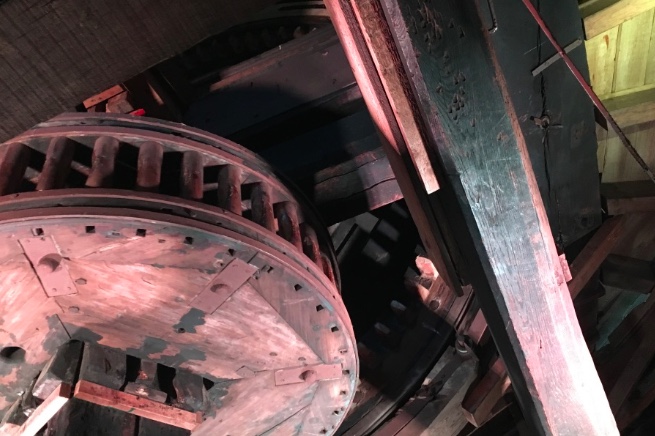

There are plenty of kinds of mill—grain mills, lumber mills, and so forth—which might be built as a business venture by an enterprising miller. But the mills at Kinderdijk existed to control the water level of the surrounding agricultural area, and as such, when they were built in the 18th century, they were owned by the Water Bureau. The Bureau hired millers and paid them a small stipend. It was a difficult life; not only was a mill a real funhouse as far as low ceilings, tilted floors and flailing machinery, but you were on duty 24/7.

Here’s the interior of a mill:

Here’s the Water Bureau building (dating from the mid-17th century):

Incidentally, the application for a post in the Water Bureau was, according to lore, to drink a gallon of wine and then compose a coherent poem. They figured if you were coolheaded enough to do that, you were coolheaded enough to oversee flood prevention.

One last interesting fact. Observe the webbed wing of the windmill:

Sails can be added or removed to increase or decrease the surface area exposed to the wind and therefore the speed at which the blades turn. In high wind, you don’t want sails, or your windmill might fly away. (Not really.) But when there’s not much wind, you want more surface area so you can take full advantage of what wind there is.

You can add two sails or four sails, but never three, or the blades will be off-balance and might snap. Our tour guide claimed that this is the origin of the phrase “three sheets to the wind.” (It isn’t. “Three sheets to the wind” refers to a backfilled jib on a sailing ship.)

Sheet = Rope used to trim (adjust) a sail.

Here is an alternative explanation for the term “three sheets to the wind”. A sheet is used to adjust the clew of the sail. If the sailors have gotten into the rum barrel and not attended to the sails, the sheets may have come loose and since they are attached to the lower windward edge of a (triangular) sail, they will blow out to leeward or downwind. If you are on a 3 masted ship, three sheets would be to the wind. The connotation is out of control, usually as a result of over imbibing.

I got my information from Wiktionary, the source of all wisdom. It might be totally wrong, but it at least sounds intelligent:

“A backfilled jib is normally a bad thing. But in a major storm when a ship is “hove to,” the helm is lashed to windward, and the jib(s) are sheeted to the windward side of the ship (sheeted to the wind) causing the ship to sit sideways to the wind and waves to minimize the distance the ship is blown off course during a storm. As the storm gets stronger, more force is required to hold the ship in position and additional jibs are sheeted to the wind. A ship that has three jibs sheeted to the wind would roll wildly from side to side and in constant danger of rolling over with each wave. Hence, a totally inebriated person is out of control and in danger of crashing, just like a ship three sheets to the wind.”

(https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/three_sheets_to_the_wind)

So the implication, at least according to this source, is not that the sailors are drunk and careless, but that the ship appears drunk because it can’t stand up straight. Does this sound like a rational explanation? I don’t remember enough of my Patrick O’Brian to be sure.