After completing the first year of my PhD studies here at UBC and having developed a good general idea of the projects I hoped to pursue, I embarked last summer on several forays out of the office, out of the lab, and out of the city to do some field work!

I am a grad student in the zoology department working with Mike Whitlock, and one of my thesis projects will be looking at adaptation in the lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), a focal species in the AdapTree project. My background now being stated, I will reveal that before starting this project I knew next to nothing about trees. I will admit that I used to call any type of evergreen tree a “pine tree”, and thankfully have since been corrected into saying “conifer”. My preliminary field work thus proved to be extremely educational in terms of my specific project goals, my exposure to field work in BC (I am from the east coast of the US, which is where the bulk of my previous field work experience accrued), my knowledge of trees, and my personal growth as a researcher. I have many people to thank along the way for this, especially those who were willing to go into the field with me to help out when I had nothing in return to offer except some beautiful scenery, fresh air, exercise, and trees. Lots of trees.

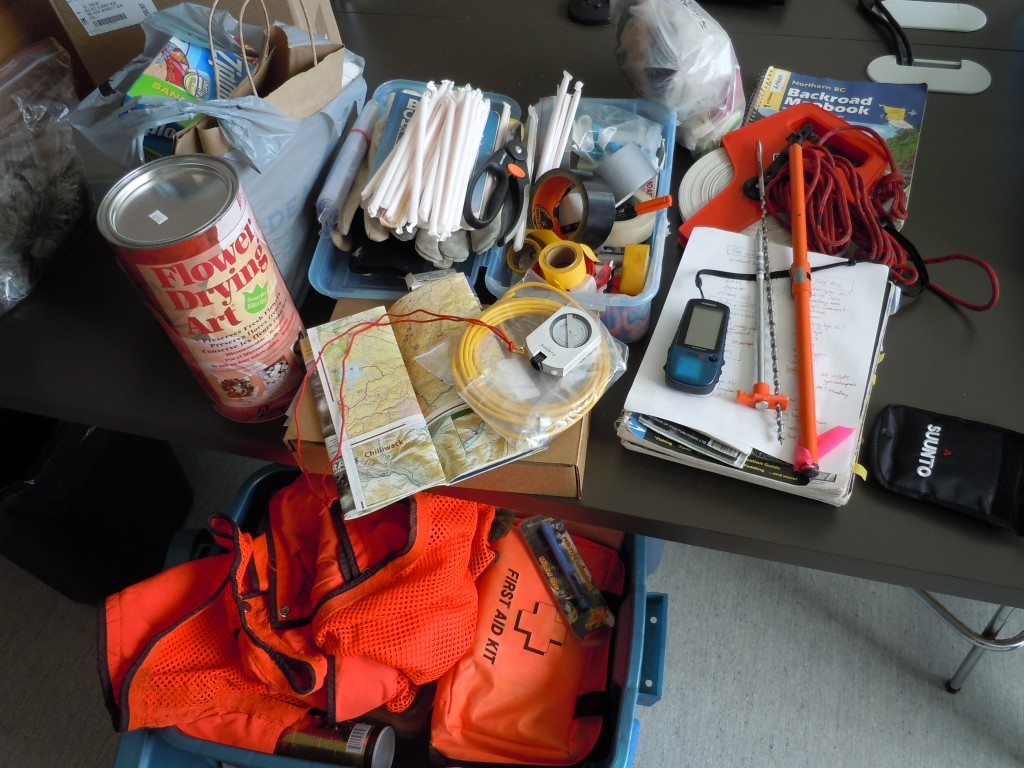

I began my first trip to the woods with a lot of planning. And I will admit that one of my favorite parts of doing scientific field work is the strange assortment of equipment any researcher needs.

I enlisted the help of two grad students from the Aitken lab: Ian, who has taught me nearly all of my conifer identification skills so that I can now proudly say I am a pro at IDing lodgepole pine, and Katha who was a visiting student from Spain and very experienced from her own field work with trees.

We headed three hours north of Vancouver, past the town of Pemberton in search of some trees to sample DNA, cores, and take some phenotypic and environmental measures. My first time being “in the middle of nowhere” in BC was quite the adventure. Upon arrival, I laid on the truck horn a bit to ward off the grizzlies that I was probably overly worried about being everywhere. We took in the beautiful view on a sunny day, latched on our bear spray, and were off!

Fortunately, no grizzlies were encountered, but unfortunately, we trudged up a very dense and steep slope with only Douglas fir in sight. With no motivation lost however, we returned to the road to practice our data collection skills on some roadside lodgepole we’d passed on the way up. Coring trees proved to be the favorite activity and measuring local density the least favorite. Though we may not have accomplished the most efficient and worthwhile sampling trip, this first outing proved vital in getting a real feel for how time-consuming different methods were, which data seemed most worthwhile, and how feasible my then-thought-out sampling scheme was. I returned to Vancouver with confidence in the skills needed to both find my species and collect the necessary data from trees.

Fortunately, no grizzlies were encountered, but unfortunately, we trudged up a very dense and steep slope with only Douglas fir in sight. With no motivation lost however, we returned to the road to practice our data collection skills on some roadside lodgepole we’d passed on the way up. Coring trees proved to be the favorite activity and measuring local density the least favorite. Though we may not have accomplished the most efficient and worthwhile sampling trip, this first outing proved vital in getting a real feel for how time-consuming different methods were, which data seemed most worthwhile, and how feasible my then-thought-out sampling scheme was. I returned to Vancouver with confidence in the skills needed to both find my species and collect the necessary data from trees.

It was thus time for field trip number 2. My labmate Katie volunteered to help out with her willing husband and dog for a trip to the interior of BC, a first for all four of us! We headed east of Hope, up the Coquihalla highway where we found lodgepole a-plenty, along with Mountain pine beetle damage and death abounding. We had two extremely successful days of sampling, covering two nice elevational transects in what we found to be a beautiful area for wandering around in the woods. My driving skills were also significantly improved on some little-used logging roads. I am no stranger to 4-wheel-drive on unsteady terrain, but it took a little bit of adjusting to get used to this when on a narrow road with trenches every hundred yards or so as drainage, dense tree and brush cover right up against the truck on one side, and essentially a cliff on the other. I was surprised to learn what kinds of roads in BC merit indication on a map.

We returned with a truck full of pine cones, pine needles, tree cores, data sheets, GPS points, sappy fingers, a tired dog, and 3 slightly dehydrated people. All in all boding well for the future. My third foray to the field took us to a site even further into the interior of BC, just outside of Vernon. I had chosen an elevational transect along a road leading up to Silver Star Mountain, which proved to be more difficult sampling than foreseen. There was little public land here, being in a more developed area, a provincial park near the top of the mountain, and a resort at the very top. Yet we still managed the full transect and remained law-abiding citizens. One of my favorite parts of the day was actually talking to the resort staff, slowly finding my way through their chain of command to get permission to sample on the property. They turned out to be extremely helpful, letting me sample wherever I liked and providing me with a local map.

However, as grad students and advisors alike know, developing projects change, sometimes quite drastically. And after this third field trip, so did mine. A major realization from my field work to this point was that I was going to be very hard-pressed to find natural stands of lodgepole pine. Every tree I had sampled so far was within logging stands, and if I wanted naturally growing trees, I would need permits to sample in a park. As it turns out though, there is an invaluable resource available for the lodgepole pine, in the form of a long-term provenance trial established in the 1970’s: the Illingworth provenance trial. With the turns my research project was taking, this resource was the perfect tool.

This provenance trial contains trees collected from 169 provenances (or sources) across the range of lodgepole pine and planted out at 60 test sites across BC. Useful phenotypic data is already available for these trees, so the only thing lacking on my end was DNA samples! Summer was drawing to a close and classes had started, so there was time left for one last weekend of field work to visit an Illingworth test site and see if my plans for this data set were feasible. I again was fortunate to have labmates volunteer for help in the field, and was happy to give my theoretician friends a chance at true field work.

We embarked to seek out the closest test site to Vancouver,somewhat  southeast of Princeton, a site called Pettigrew Creek. I received copious preparatory help from Nick Ukrainetz, the lodgepole pine breeder for the BC Ministry of Forests, who provided detailed access notes and site maps. As one might expect however, nearly 40-year-old research plots are not as easy to find as they once were. We succeeded in finding one out of two blocks planted at this site after much driving and searching through the woods. At one point, I am entirely certain that we left the road to find the trial site, walked around and past it, and managed to return to the road entirely looping around the research plot. Luckily, on the second go-around, we spotted an old sign, half buried in the dirt, identifying that we were on the right track.

southeast of Princeton, a site called Pettigrew Creek. I received copious preparatory help from Nick Ukrainetz, the lodgepole pine breeder for the BC Ministry of Forests, who provided detailed access notes and site maps. As one might expect however, nearly 40-year-old research plots are not as easy to find as they once were. We succeeded in finding one out of two blocks planted at this site after much driving and searching through the woods. At one point, I am entirely certain that we left the road to find the trial site, walked around and past it, and managed to return to the road entirely looping around the research plot. Luckily, on the second go-around, we spotted an old sign, half buried in the dirt, identifying that we were on the right track.

We fanned out into the woods, and like finding buried treasure, spotted man-made posts, labelled trees, and painted signs. Eureka!

We spent the rest of the day successfully sampling tree heights, DBH’s, and collecting cones and needles for DNA samples. The highlight of this trip would definitely be the testing of a new method for collecting needles from trees with branches too high for the pruning poles to reach: slingshot. I had spent a good deal of time prior to this trip asking around different forestry labs how they collected DNA from very tall trees, and as I did not want to invest in either a rifle or an expensive, multi-telescoping pole, slingshot became the tool of choice. It proved somewhat time-consuming and dangerous to shoot nearly straight in the air, with pieces of gravel ricocheting off of branches and trickling back down to where we stood, but it was fun and we obtained every single DNA sample we sought which I call a success.

I found this summer of field work, despite some hitches, to be priceless. My advice to any beginning grad students out there seeking to do field work of their own is this. Definitely plan your own preliminary outings or tests. Something always goes wrong when working in the field, so you just need to be prepared. I do not feel as if any of my time in the field was wasted, and even if all of my samples will not end up being analyzed for my thesis, they also provide me with material to test my genetic methods on to ensure that no issues arise on that front. There is no amount of planning that can replace the actual experience of being in the field, because that is where you can learn the most about your system. And with the proper preparation and hands-on experience, when the time comes for the real work, your stress level will hopefully be much diminished knowing that you are capable of the task at hand. I now look forward to the coming summer knowing what I can expect to find for the most part.

Lastly, I want to end this post with a few last thoughts that struck me. It truly amazed me how much land there really is in BC, as well as how much logging. Hearing numbers and acres in my head was nothing at all like seeing an entire mountainside swept clear.

As opposed to the cow pastures and corn fields I am accustomed to, it is clear that the resource here is timber. It is also clear that BC has vast areas of unpopulated land, which was the strangest experience for me. Where I am from, you are hard-pressed to drive more than an hour without seeing a gas station or a rest stop or a town. Here, you can drive half a day or more and see no signs of habitation. BC is full of beautiful untamed areas, and I feel like my home state’s motto of “Wild and Wonderful” is just as fitting here.

Thank you for submitting this post to our February Berry-Go-round carnival! It is now up at Foothills Fancies. Happy reading!