In today’s lecture, it was interesting how Hitchcock’s obsession for casting female leading roles as blondes (if and when possible) was pointed out. It was interesting, partly in the fact that Hitchcock loved to make these blonde characters suffer throughout his films and how the stereotype of a gorgeous, ditzy, blonde was used. Of course, this interpretation comes to mind due to modern day (give or take a couple of decades) tropes of a unique and glamorous, Caucasian woman. Either way, the blondes were casted and Hitchcock needed them to become victims as shown in Vertigo.

We can see that in the apartment scene where Scottie interrogates Judy, the blonde vs. brunette stereotype ironically appears. Scottie needs Judy to become Madeline in every way possible in order to fulfil his own fetishes and obsessions. This means that the independent, common, rational Judy must disappear. As the scene unfolds, we see that the self-sufficient, brunette Judy breaks under the pressure of Scottie’s interrogation and complies with his will to transform her. Lo and behold, Judy allows herself to become blonde and in doing so, adopts/returns to a submissive and helpless woman.

I’m not saying that Hitchcock had any intentions to symbolize the helpless woman as a blonde and represent the independent one as a brunette, but it is definitely amusing how well this conveyed the blonde as the fetishized object of gaze. If anything, it was more logical for Hitchcock to represent blonde women as objects of the male gaze in the film as the hair color itself draws the audience’s attention. If we look at the previous scene of Scottie viewing both Gavin and “Madeline” in the restaurant this becomes especially apparent. Madeline (Judy) is viewed through the “double frame” by Scottie and Scottie alone; her attire is much brighter in comparison to the rest of the diners who dress in black or obscure colors. For her beauty to be noticed, seen, and acknowledged, she must be different.

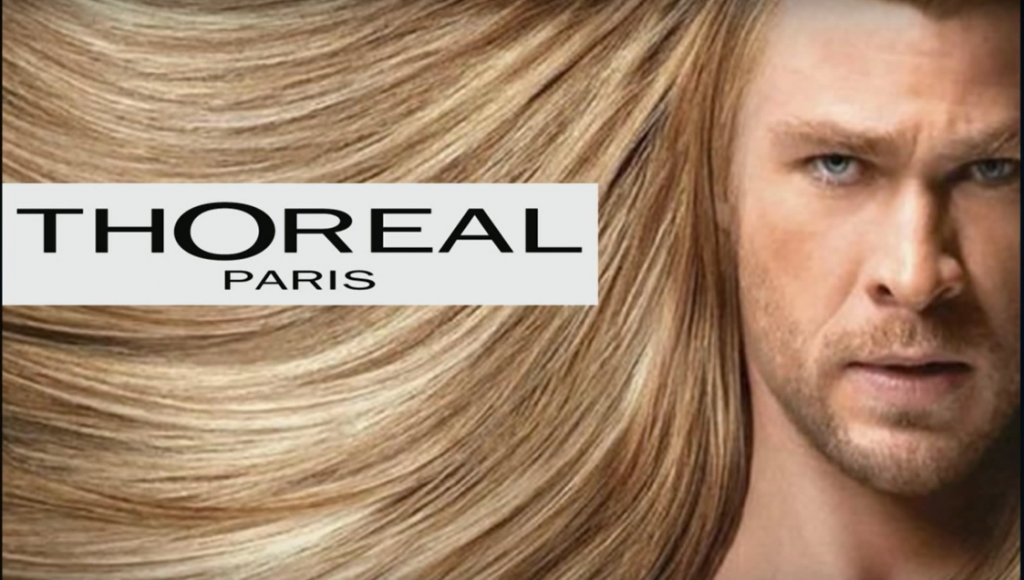

Taking this back to present day, I wonder just how relevant the blonde vs. brunette contrast is. Perhaps it is as obvious as the rarity of blonde genetics that makes these individuals physically unique, idealized and empowered (even if they are fetishized) in many advertisements/media we see today.

I mean …

… this caught your attention, didn’t it?

(Link to the full interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-IYMYOZ7yKw)