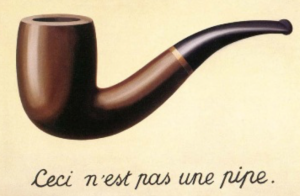

In Thursday’s seminar, we discussed the growing skepticism regarding metanarratives which defines postmodernism. Postmodernism challenges a single metanarrative by encouraging localized and diverse narratives; postmodern thinkers claim that existence is too complex to simply be told in a single narrative.

The Law of Attraction is an increasingly popular paradigm in the western world. Historians claim it has roots in the American New Thought movement and German Idealism; however, it appears to also have emerged in the East in Vedanta, ancient Chinese philosophy and many other schools of thought. The Law of Attraction (by my understanding) is a belief that the universe is more complex than can be understood by human perception. As a result, our perceptions of reality are based on our own thought projections and beliefs — whatever it is that we focus on and wish to see, will be able to manifest itself (like attracts like).

For example, if a person tells themselves “I always seem to be sick,” then their body would subconsciously manifest illness. This may not occur instantly, but the Law of Attraction states that it opens the possibility for sickness to occur. This manifestation may also be subtle — perhaps the individual in question begins to forget washing their hands, or begin to eat questionable food — regardless, the mental thought (sickness in this case) would be rendered more likely to materialize than if their belief was “I rarely get sick”.

This is one simplistic example in what is a complex philosophy — nevertheless, the basic premise of the Law of Attraction is able to simultaneously support and challenge postmodernism as a whole. The Law would allow each person in the world to experience a different reality — this fits with the postmodernist idea of “petits réchits”. However, the idea that each person’s interpretation of the world is different stems from a single basic metanarrative: whatever one experiences is manifested by themselves. In this case, the Law of Attraction simultaneously supports and contradicts the anti-metanarrative ideas of postmodernism.

One criticism of the Law of Attraction has been its lack of falsifiability (the ability to prove a hypothesis as false). Scientists claim that the Law is not scientifically testable. If the experiment results in the claim that the Law of Attraction does not work, believers would merely say that the researcher simply manifested the result which they wished to see, and that in itself is able to prove the Law. As a result of this lack of falsifiability, the Law of Attraction has subsequently been given little thought under scientific study — but this may just be further proof of the issues with using science as a metanarrative.