Scouring coastal Alaskan forests : a journey through the past (Part 2)

Two wonderful weeks of hard work on the Kodiak Archipelago resulted in a truck loaded with 350 silica-dried needle samples and about as many tree cores from Sitka spruce forests. Happy and satisfied with the amount and spatial distribution of these tree samples, I embark on the ferry full of confidence about the second part of the trip: Sampling on the Kenai Peninsula.

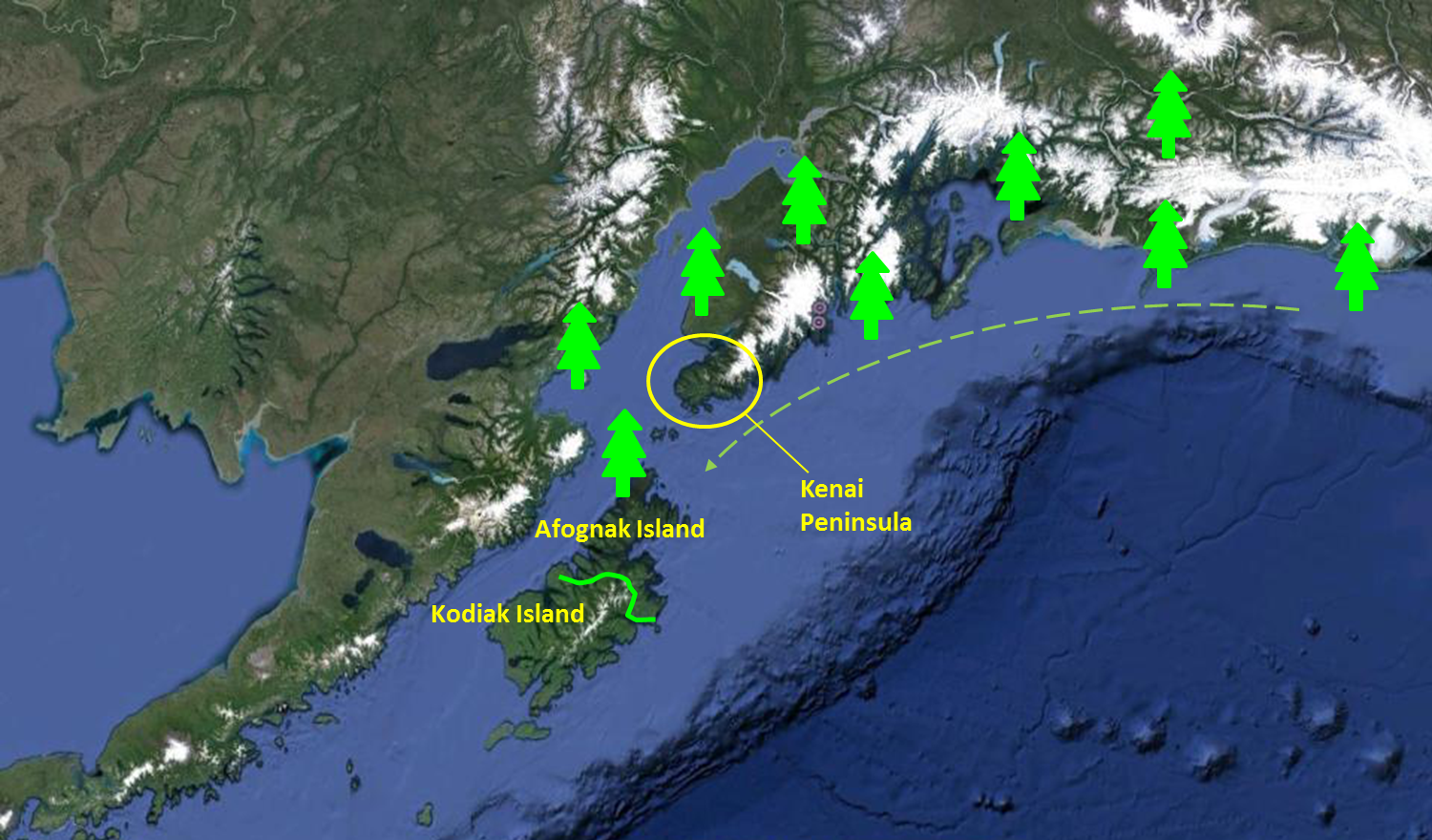

Back on the continent, my main objective is to find old-growth forests of Sitka spruce and apply the same sampling design. By doing so, I will be able to compare the genetic make-up of a long-established forest to the young forests of the Kodiak Archipelago. I chose the Kenai Peninsula because it is the most likely origin of the trees that established on Afognak and Kodiak Island.

This second chapter to the Alaska journey will provide the essential baseline data for my project and will help answering the following questions:

To what extent is population expansion linked to a drop in genetic diversity?

Are trees at the front of expansion experiencing higher levels of inbreeding than trees in core populations? Are they subject to lower levels of selective pressure?

Do deleterious / advantageous mutations spread more easily during population expansion?

Team number 2 is waiting for me in Anchorage: Jon and Vincent, fresh out of the plane. Two highly motivated Aitken Lab members. Two masters of tree-spotting, mushroom-picking, blueberry-gathering, and wild-cooking. Already on the first day I am tempted to re-name them Witty and Cheeky. But they ended up being “Yonathaaan” (with the strongest German accent you can adopt) and “Young Padawan”.

While the difficulty on Kodiak was to get to big trees before the loggers, the difficulty on the Kenai was to get to big trees before the bark beetle. A devastating outbreak in the 1990s left very little of the pristine, old-growth spruce forest I was looking for. A lot of remaining old-growth lies in a thin strip of wet lowland crunched between the sea and the gigantic Harding Icefield, an impossible target for us and Bean, who likes roads more than glaciers and waves.

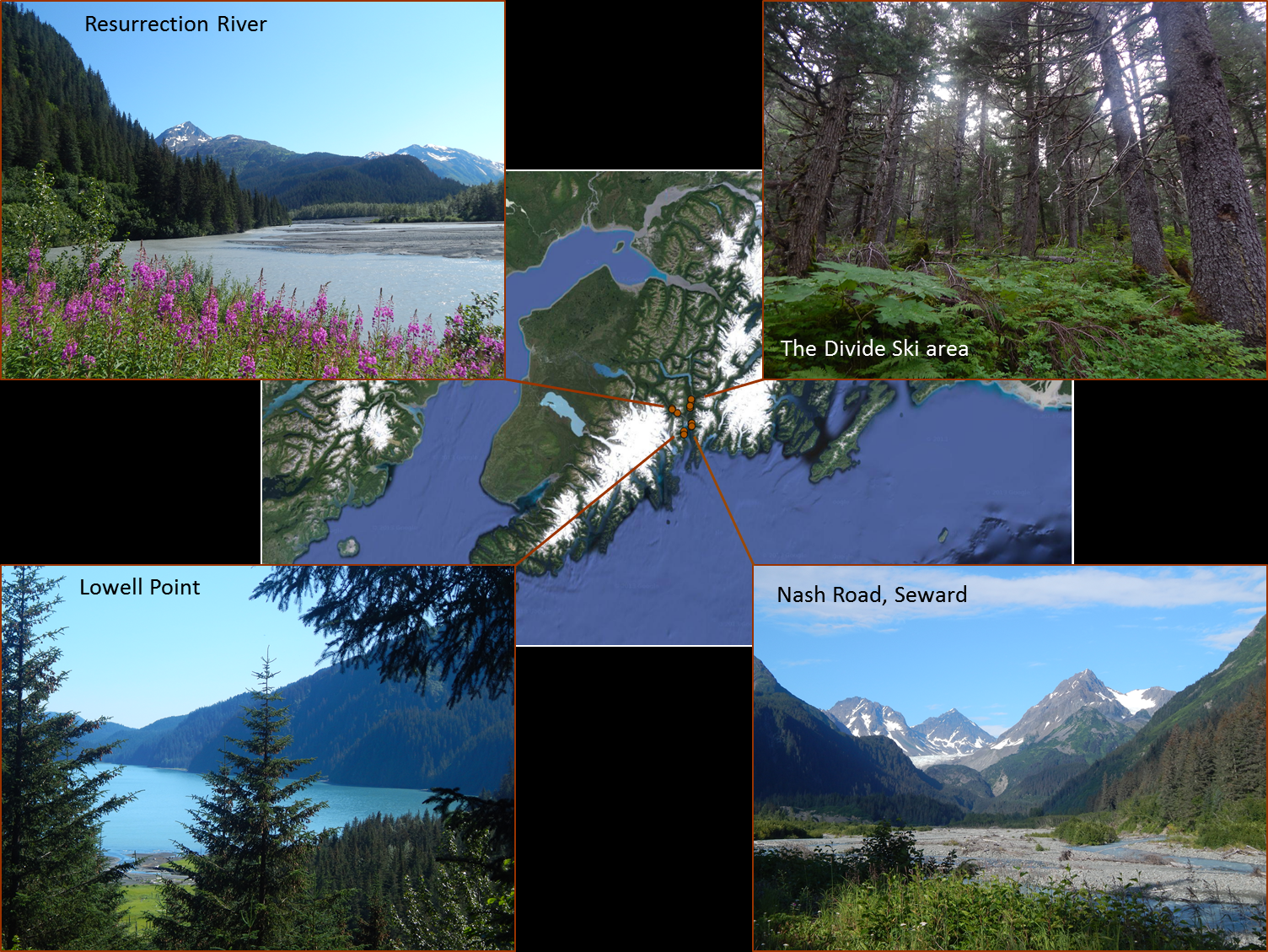

But thanks to the help of Ed Berg, bark beetle expert, John Morton, wildlife biologist, and our flawless determination, we finally manage to find beautiful, road-accessible stands of pure Sitka or mixed Sitka spruce-western hemlock forests around the Seward Inlet.

After stalling a few times due to excessive scenic landscapes, we’re back in the coring-trunks-and-snipping-twigs business! We keep the same sampling scheme as on the Kodiak Archipelago: collecting equal numbers of tree needle and tree cores among 4 levels of forest structure (see previous post for details) in several locations, and keeping a distance of at least 50 m between sampled trees. The most striking difference in forest structure with Kodiak Island is that there is no “proper” tree of level 5. For sure there are very large trees (winning DBH: 138cm!), but none of them shows signs of open-growth (large lower branches). To me, this confirms that the canopy on the Kenai is way older than the oldest trees, unlike the canopy of Kodiak Island.

On the left, a Kodiak #5. On the right, a Kenai #5. Note: the scale on both pictures is represented by a normal-sized human being.

Although finding stands with no sign of recent disturbances was a real challenge on this part of the field trip, we managed to find four suitable sampling areas around the Seward inlet and added 197 trees to the collection. Early August, more than six weeks after having left from Vancouver with Ian, Bean and Jethro, it is time to return home. With a few kilometers added to Bean’s odometer, new or reinforced friendship bounds, beautiful memories of wild landscapes, a total of 550 tree samples and exciting prospects for my PhD research, I can’t wait to process all the data…. and go back on more adventures!