Matsuo Basho is one the most outstanding Japanese poets of haiku – a short form of Japanese poetry (Basho, 1996; Basho & Barnhill, 2005). He was born in 1644 in Ueno, Iga Province, to a low-ranking samurai family. Basho started writing poems as early as 1662. He was part of the Danrin School, where he participated in numerous competitions. He would later become a judge of poetry competitions and acquire students of his own, become a lay monk, and establish his own poetry school. Basho’s poems were influenced by his intimate relationships, especially with friends, as well as Zen and Chinese Daoism (Basho & Barnhill, 2005).

Feudal stability characterized the Tokugawa Period (1600-1868) (Basho & Barnhill, 2005; Downer, 1989). Hence, travelers could travel safely. Improvements in social mobility facilitated the widespread of arts and throughout Japan, regardless of class, with the merchant class taking on the arts. The Haikai no renga, a comic-linked verse, was significantly popular among samurai and merchants. This is how poetry reached Basho. However, in 1666, Basho’s friend Yoshitada died suddenly, making him consider leaving secular life. The flourishing arts made it possible for gifted writers to remove themselves from their daily life and become master poets. This is the path that Basho followed (Basho & Barnhill, 2005).

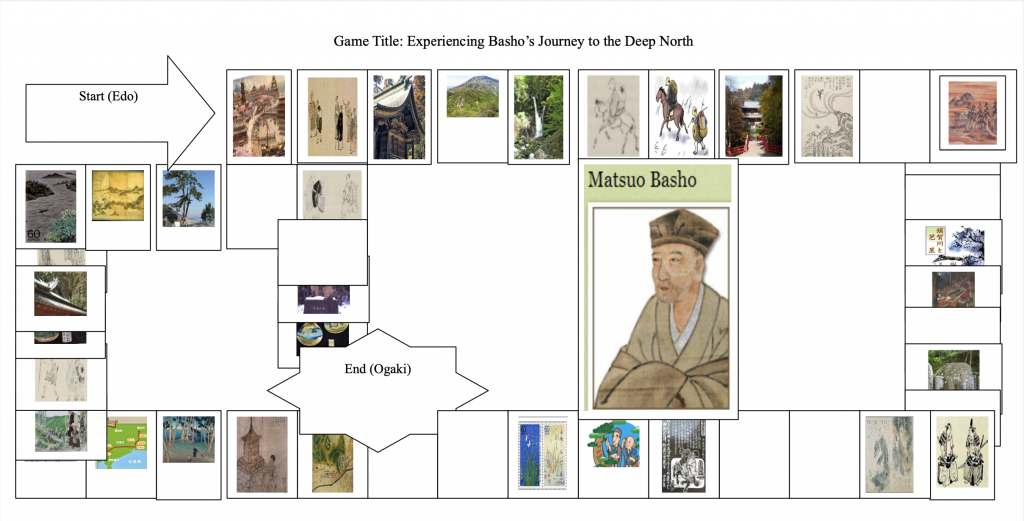

In the late spring (May) of 1689, Basho set off for a 2,000-kilometer journey from Edo (currently Tokyo) to the northern interior of Japan, as indicated in figure 1 (Basho & Barnhill, 2005). This journey happened to be among the last one, and it generated the infamous The Narrow Road to the Deep North (Oku no hosomichi). When starting, Basho admits feeling old and frail, but he felt compelled to make this journey. He dressed like a monk, carrying a wide-brimmed sedge hat and bamboo staff. As a lay monk, he owned nothing, relying on friends, disciples, and admirers (Downer, 1989).

Basho traveled for many reasons, including for religious and poetic purposes. At the time, traveling or wandering the countryside was viewed as an ascetic practice that helped shape and sharpen sacred visions and poetic creativity (Basho & Barnhill, 2005). Additionally, going on such journeys helped ascetics, monks, and poets remember those who had died before them and their legacy, as observed in Basho’s visits to monasteries and graves of famous people in his historical timeline. He also traveled to acquire more disciples (as he was a master in his own school) and spread his poetry throughout Japan.

It seems that to Basho, travel was more about the experience than the destination. From his poems, one can deduce that he walked to reflect and interact with people, nature, and culture. When leaving Edo, for example, he feels burdened by the goodbyes from family and friends. Although he is old and frail, he cannot leave these memories behind as a human being; it is his responsibility to carry the burden of sustaining relationships with friends and family rather than walk alone. Even so, he is propelled to keep moving on, whether through friends or to reach places, while never forgetting memories, and creating new friends, or finding new encounters at every turn (Kerkham, 2006). Therefore, this sugoroku is intended to be a game played with friends. As players experience Basho’s journey, they learn more about Japan and various essential aspects of the journey. Drawing from Basho’s poems, these experiences are worthy particularly because they represent the temporality of life.

Game Instructions:

Start point: (Edo)

End point: (Ogaki).

Number of players: 2-4.

All boxes, regardless of size and with or without visuals, hold equal importance. Note that only one player (the first to get to Ogaki) will be crowned Basho. The game ends when the first player finishes the game. If all players are unsuccessful in any of the steps, they stay in that stage until they are able to break through and continue their journeys.

The Shortest Way to Ogaki:

Roll numbers 1 and 3 when the game starts and jump past the Shirakawa Barrier (step 11). When successful, the player is allowed to cast the dice again. If the player gets dice number 1 or 6, they jump past the Great Gate at Date (to step 22). The player then rolls the dice again twice. Dice number 3 and 1 take the player past the Shitomae Barrier (Step 33). The player then casts the dice again. If they get dice number 2 or 5, it is game over as that skips them to Ogaki, the finishing line.

The Long Way to Ogaki:

References:

Basho, M. (1966). The Narrow road to the deep north, and other travel sketches (Vol. 185) (N. Yuasa, Trans.). Penguin.

Basho, M., & Barnhill, D. M. (2005). The narrow road to the deep north. In Basho’s journey: The literary prose of Matsuo Basho (D. M. Barnhill, Trans.). State University of New York Press.

Downer, L. (1989). On the narrow road to the deep north: Journey into a lost Japan. Vintage. Kerkham, E. (2006). Matsuo Basho’s poetic spaces: Exploring haikai intersections. Palgrave MacMillan.