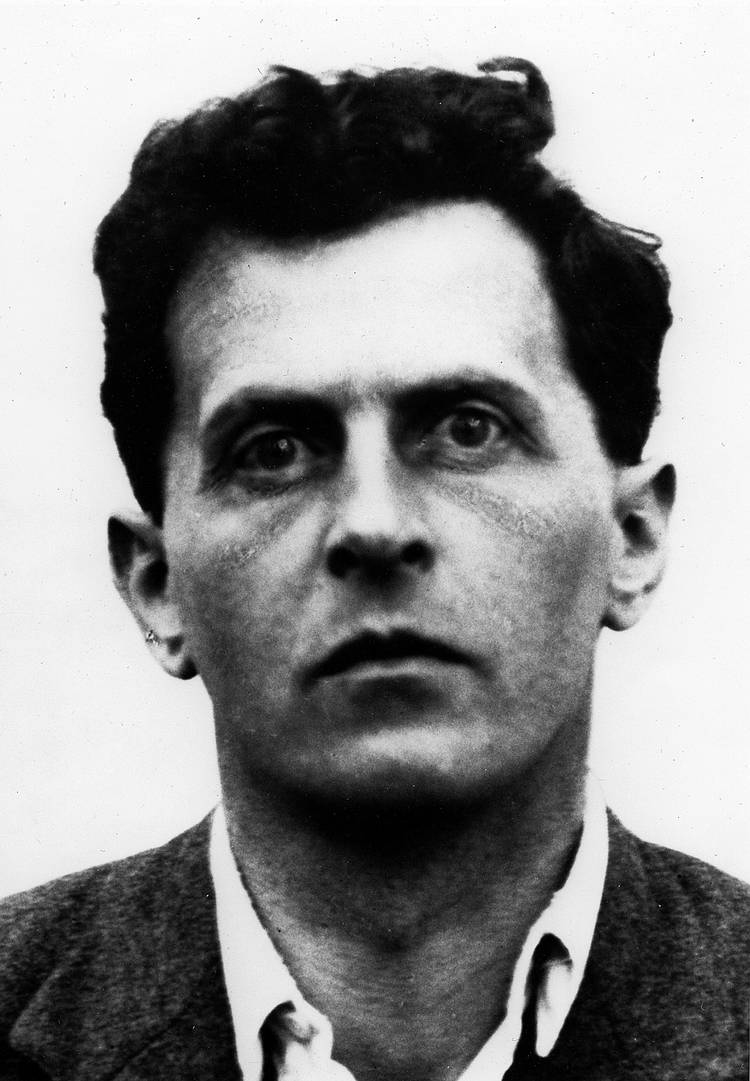

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s ideas had a huge effect on the way that I think about language, and I felt the need to revisit these ideas and to look at them a little more carefully before I delve any deeper into the study of linguistics. The summaries of his ideas in the first two parts of this post were written as an exercise of refamiliarising myself with Wittgenstein’s philosophy. There’s probably clearer explanations of these ideas elsewhere online, but I think I’ve done a passable job.

Part 1 – The Tractatus

In his first book, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Wittgenstein puts forth his picture theory of language. The basic idea here is that language corresponds to reality by picturing it. When we say or think of the word ‘flower’, a picture of a flower appears in our mind. By ordering words (and the pictures they bring to mind) into sentences, we construct a mental image of what we’re hearing. Unfortunately, this really only works properly for straightforward sentences about physical objects in the real world.

“The flower is on the table.” or “My dog is swimming in the river.” are fine. These statements will call similar images into the minds of different people, and the differences between our mental images can be decreased by adding descriptive language to our sentences. Our capacity for image forming allows us to imagine things that we have not actually seen. Sounds pretty good, right?

But what picture comes to mind when you hear a sentence like, “Phenomenology is a presuppositionless science of essences that proceeds through pure intuition.”? Maybe you can form an image of this sentence, but you will concede that it is very unlikely that anyone else will form the same or even a similar image. Statements about philosophical issues don’t form neat little mental images. Wittgenstein’s solution to this problem? Don’t talk about philosophical issues.

I love Wittgenstein.

Now, do human beings find it difficult to express philosophical truths because:

(a) our language is not complex enough to discuss certain philosophical issues,

or

(b) because these philosophical issues are actually illusory phantoms that only appear because of the limits/shortcomings of human language?

To put it another way, are philosophical issues genuinely outside the realm of human comprehension, or are they actually non-issues that only appear because our language is imperfect?

For example, whether or not God exists is a popular philosophical debate. Is the lack of a resolution to this debate due to the fact that our language is simply not developed enough to express/comprehend the divine, or is it because we only ever postulated a God to answer odd questions that have no sensible corresponding mental image like, “why are we here?” or “why does evil exist?”?

I don’t know the answer. I’d say it’s a mix of (a) and (b). I’m sure that there are certain topics that our language just isn’t equipped to deal with. Doesn’t quantum physics show that a thing can be two places at once? Our language won’t make talking about that easy. Language changes though, and there’s always hope that what we can’t talk about today, we’ll figure out tomorrow. There has to be limits to language though, and those limits are going to be very difficult to pin down. I was listening to a podcast on Wittgenstein, and Barry Smith pointed this out. He said that “He (Ludwig) was worried about how we actually describe limits without breaching them, without being outside them”. If we don’t know where the line is, how can we ever know that we’re about to cross it and fall head first into pseudophilsophical nonsense?

Part 2 – The Philosophical Investigations

Wittgenstein believed that his Tractatus had solved the problems of philosophy or that it had at least come as close to solving them as was possible. After writing this monumental work, he quit philosophy and became a school teacher. After a few years, he changed his mind. He no longer believed that language was merely a means of painting mental pictures. In his later work, he claims that meaning derives from how words are used instead of from their correspondence with the physical world. To put it more simply: what a word means depends on how it is being used. (The usage is its meaning.) To explain how this is, Wittgenstein introduces his concept of language games.

Ludwig posited that language has a myriad of uses. We don’t just use it to make empirical claims about the observable universe such as “The chair is red” or “The boy is 5 foot tall”. We also use language to pray, to express frustration, to condone, to accuse, to insult, to exaggerate and so on. Think of how the word red is being used in the following sentences:

- The ball is red.

- Her favourite colour is red.

- He was caught red handed.

- I’m seeing red.

- Boy, is my face red?!

- The Reds won the game!

- The Reds won the election!

- This curry is red hot!

To native English speakers, these sentences are easily understood. In the first sentence, red is being used to describe a physical object. In the second, it’s redness itself and not a red object being discussed. In the third sentence, red is being used to imply guilt. In the fourth, it is being used to express anger. To a language learner, this will be very confusing, and Wittgenstein’s picture theory can’t really account for these different uses of the same word.

The different uses of the word red above represent different language games. Language games is just a name for the many different uses of language. Expressing emotion is a different language game to describing a physical object. The difficulty is that both of these language games use the same words. Wittgenstein now claims that the problems of philosophy (and many other problems) are caused by people not understanding which language game they should be playing.

Although the sentence ‘Are you Irish?’ looks like a lot like the sentence ‘Are you free?’, the process of answering these questions is very different. The only visible (or audible) difference between the sentences are the words ‘Irish’ and ‘free’, both of which are adjectives. Whether or not I am Irish is an empirical issue. I can answer this question by producing my passport. Whether or not I am free is far more complicated – first of all, I must figure out if the person asking the question is asking me if I am currently free to grab a cappuccino at Starbucks or if they are asking a deeper philosophical question that will require a resolution to the apparent conflict between determinism and my true will. The verbal similarities between the two questions leads people to think that they can be answered in a similar fashion, but this is obviously not the case.

While the main point of Wittgenstein’s picture theory seems to be negated by his later ‘usage theory’, I believe that a lot of what he said in describing the former theory is still very relevant to the latter. In fact, with regards to the specific element of his work that I’m interested in, Wittgenstein’s later ideas serve as a development on his earlier ones rather than a refutation. Philosophical problems remain very much the product of the shortcomings of language.

Just as a game of soccer is not played on a chessboard, a discussion of the compatibility of free will and determinism should not follow the same rules as a discussion of ones nationality. Unfortunately, Wittgenstein does not put forth a set of rules for the philosophical discussion. I think Ryle did a pretty good job of providing the rules for that particular discussion by marking category mistakes as a foul, but the rules for other philosophical discussions and even the possibility of these rules sensibly existing are still rather unclear.

Part 3 – More Investigations

I have previously discussed three potential causes of philosophical problems:

1. People using language poorly. (This includes Rylean category mistakes such as the mind/body problem)

2. Language simply not being equipped to deal with certain issues. (What is the meaning of life?)

3. Philosophical bogeys arising as people encounter the limits of language. (This is like a combination of the first two issues.)

To emphasise the linguistic basis of the problems of philosophy, I want to return to Wittgenstein’s concept of language games.

Language games appear in the Philosophical Investigations to give an example of an incomplete picture of language. Imagine two immigrant bricklayers working together. Both of these men are from different countries and speak different languages, but their work is relatively simple. One of them, let’s call him A, actually builds the wall, while the other, a chap named B, provides A with the necessary materials to do so. Maybe sometimes they switch roles so they don’t get too bored. The only three things that they ever use are bricks, mortar and a trowel. (This is not the exact analogy that Wittgenstein uses, but it’s close enough for you to get the idea.) Given the simple nature of A and B’s relationship, the only things that they ever need say to each other are commands that indicate the need for a brick, some cement or the trowel. Although they don’t speak the same language they agree on arbitrary sounds that correspond to these commands. For A and B, the utterance ‘gah’ means ‘Give me a brick.’, the utterance ‘mah’ means ‘Give me some cement.’, and the utterance ‘bah’ means ‘Give me a trowel.’ When A says ‘gah, B gives him a brick. When B says ‘mah’, A gives him some cement.

Now it’s quite obvious that real world relations are never this simple, but as a hypothetical situation, this isn’t particularly difficult to imagine. Some philosophical arguments require people to imagine such absurd scenarios that they become infuriating, but Wittgenstein’s idea of the two construction workers is easy to follow because similar situations are probably a fairly common occurrence amoungst immigrant workers.

The idea of these two workers and their direct but very limited ability to communicate is supposed to emphasise the shortcomings of Wittgenstein’s earlier picture theory of language. In the very simplistic “language” of these two men, words might very well represent pictures. When A says ‘bah’, both he and B momentarily hold an image of the trowel in their heads. The problem for Wittgenstein is that the picture theory of language only works if we view all language as being as simplistic as the communication between the two bricklayers. While these men may have developed a system of communication that allows them to build walls efficiently, neither man can express his fondness for the other, his appreciation for the fine walls they have been building or the existential angst that builds up when one spends all day on a construction site. Wittgenstein seems to concede that these men may have developed a language but that their language does not represent all that Language (with a capital L) is.

While Wittgenstein’s actual point is that Language is far more complex than the system of communication developed by A and B, I’m still fascinated by how much the two systems have in common. Yes, our language has more words, but our vocabulary is also finite. An English speaker with a high vocabulary supposedly knows about 50,000 words. The men who have three words can’t talk about the weather or where their kids go to school, and while 50,000 words makes a lot more possible for us, this level of word power doubtlessly has limits too. We can’t possibly explain everything. It won’t matter how smart we are or how hard we try; we just don’t have the words to talk about certain things.

And it’s that idea that brings us back to the eerie yet beautiful final line of the Tractatus, “Whereof we cannot speak, thereof we must be silent.” While Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations points out the shortcomings of some of his earlier ideas, it strengthens the argument for others. The final message of the Tractatus is safe, and it’s that line that has always seemed the most potent for me. I remember reading the Tao Te Ching for the first time and being shocked with the similarity of its opening passage with the closing line of the Tractatus. Compare “The name that can be named is not the eternal name.” with “Whereof we cannot speak, thereof we must be silent.” I later discovered that many others have also noticed this similarity, but I still think it’s interesting enough to mention again. Considering the millennia, thousands of miles and radically different cultures that separated Wittgenstein and Lao Tzu, they make a surprisingly similar point – language can’t do everything we want it to do.

I’m going to leave it there. The notion of writing a 2300 word essay on Wittgenstein in my free time would have seemed very unlikely to me a few years ago, but I’m almost more surprised that I still have lots to say about him. I’m quite sure his ideas will pop up on this blog in the future. To write with full disclosure, I must admit that although I have attempted to read both of Wittgenstein’s major works, I have read neither in their entirety. Despite several attempts, I’ve only ever made it through a few pages of the Tractatus before being completely unable to follow what was going on. I fared quite a bit better with the Philosophical Investigations, but it’s quite dense and quite repetitive, and I gave up before I got half way through. That being said, I’ve read several books and papers on his writings, listened to a bunch of lectures about his work, and watched this cool documentary and the Derek Jarman film about him several times. I’m confident in saying that I have a pretty good idea of what he was talking about. I’m not an expert on this though, and if I have misunderstood something or if what I’m saying is really dumb, I would be genuinely appreciative of any feedback.

Not, I guess.

Not, I guess. Robert Anton Wilson, an advocate of E-Prime

Robert Anton Wilson, an advocate of E-Prime “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.”

“Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.”

The Concept of Mind (1949) is the only thing I’ve read by Ryle. In truth, I only read a few chapters.

The Concept of Mind (1949) is the only thing I’ve read by Ryle. In truth, I only read a few chapters.