Chamberlin puts the concept of home in parallel with the relationship between imagination and reality and how both are human perceptions that tend to be socially constructed. So I found the explanation of “home” in something he could appreciate – a fantasy story.

Bilbo describes home as where his books are while the dwarves are trying to reclaim the mountain that was taken from them forcefully by a dragon. Bilbo admits that while he belongs in a peaceful home reading his books from his armchair, he has left that home in order to help the dwarves regain theirs. It’s easy to relate the two stories; The Hobbit and that of the Indigenous peoples around the globe (who have more than a single dragon to conquer in order to persevere). This story is both real and imaginary, like Chamberlin’s examination in If This is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?, however Bilbo’s concept of ‘home’ translates easily into our world.

‘Home’ is a figurative idea that we are taught to believe in as well as a reality we experience (Chamberlin 78). Home is where the heart is; where we curl up with a good book; where we lay our heads; where our ancestors lived; where our family is; where you keep your underwear (according to a 4 year old I know). I can relate to all of these as I’m sure you can as well. As Chamberlin consistently reiterates, the stories that make up our individual lives as well as our cultural lives are necessary and will connect us. The internet has provided a way for millions of stories to be shared from a public copy of The Survivors Speak, which reports stories of the survivors of Residential Schools who can now know for sure that Canadians know the truth, to the stories of immigrants who arrived at Pier 21 who faced harsh conditions and risked everything from their homeland to move here. All of these stories share a similar tone of distress and with these stories empathy can be gained and show the interconnection between what has become “Us” and “Them”.

I find that the common connection between the notions of ‘home’ across all cultures is that it is a place of belonging. Belonging is at the foundation of Canada for both those who were always here and those who have come here and from this similarity common ground can (almost literally) be achieved.

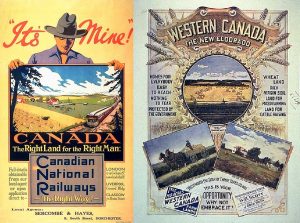

However, the differences between culturally practices have prevented this common ground to be reached and instead consequences such as contradictory claims on land and home have emerged. The immigrants were told ‘come to Canada, there’s plenty of land for you to own’ which for many was a dream come true. Advertisements presented a land of opportunity, not conflict. Many immigrants wouldn’t have realized their impact on the Indigenous peoples because in the same way that Chamberlin is told he can’t eat peas with a knife, the settlers didn’t understand land ownership in any terms other than papers and laws. To them this new land was the home they had worked so hard for and the Indigenous weren’t the owners. On the other side, the Indigenous peoples had a different notion of how one owns land. Through these differences conflicts surrounding land occurred despite the consistent notion that the land is ‘home’ to both groups.

Chamberlin claims that by changing the claim to the land it wouldn’t necessarily mean having anyone move or giving any homes up, but rather providing an appropriate association between Canada’s land and her Indigenous peoples in the same way we associate the word home with both a reality and an idea. In fantasy terms, this means allowing the dwarves claim on the mountain and internationally recognizing it, but nationally sharing in the profits.

Works Cited

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If This Is Your Land Where Are Your Stories? Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2003. Print.

The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. Dir. Peter Jackson. Perf. Martin Freeman, Ian McKellen, Richard Armitage. New Line Cinema, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), 2012. Online.

“Culture Trunks.” Pier 21. Canadian Museum of Immigration: Pier 21, 2016. Web. 20 May 2016.

Hi Charlie,

I really enjoyed reading this – and not just because you found a way to get Tolkien reference in there.

I agree that publications like The Survivors Speak, and other independent sources online, are an incredibly valuable tool to communicating stories and reach a much larger audience than what was previously accessible to Aboriginal peoples and other victims of horrific events globally. The www has provided a landscape for people who are otherwise silenced the opportunity to have agency over their own voices and stories, and I think that’s really incredibly. Although, obviously, manipulation, commodification and appropriation can happen on any platform.

The one question I do have about this post is when you said: “Many immigrants wouldn’t have realized their impact on the Indigenous peoples because in the same way that Chamberlin is told he can’t eat peas with a knife, the settlers didn’t understand land ownership in any terms other than papers and laws. To them this new land was the home they had worked so hard for and the Indigenous weren’t the owners.” I’m wondering if this is in direct response to something Chamberlin said? The difficulties I’m having is when we assume innocence of settler’s intentions when there is plenty of recordings of intentional displacement, removal and violently wiping out of Indigenous communities in Canada to create “home”. Of course not every settler has this as their story, but many many do.

Looking forward to reading your response as well as your follow up blogs in the future 🙂

Heather

Hi Charlie (and Heather!),

Thank you for your post, Charlie, and some important conversation-starters in your reply, Heather. Overall I think your post includes some eloquent descriptions of home, and also represents that there are many “sides” or stories that can describe an event or situation. This is an important point, as it is necessary to keep in mind that European settlers had stories and struggles of their own; on an individual level, many people were simply trying to create better lives for their families. However, as Heather mentioned, it is problematic to assert that the genocide of Aboriginal peoples across Canada was a simple misunderstanding about land ownership. I disagree that many settlers didn’t “realize” their impact on Indigenous people; I think they very much understood it, and felt justified anyway. Many people who came to these lands believed that they were culturally, morally, and intellectually superior to Indigenous peoples, justifying their actions (residential schools, violence, cultural genocide) with this mindset.

When Chamberlin discusses the importance of finding “common ground” among non-Indigenous and Indigenous peoples in Canada, I understood it as coming from a place of understanding that most of the settlers (non-Indigenous) people living in Canada do not know any other home. Therefore, it is important to recognize and apologize for our deplorable actions, while acknowledging that we now share this place and call it home. Finally, I am not certain that I understand your analogy with the dwarves on the mountain and nationally sharing the profits. In this analogy, who are the Indigenous/non-Indigenous people, if you mean it in that way? Also, I think that reducing our home to the idea of “profit sharing” is in contradiction with your poignant discussion on home throughout the rest of your piece. I do not think that you meant it in a strictly capitalist sense, but I think it is an interesting word choice reflecting and reinforcing some of the attitudes of many settlers: that we own the land and can take from it what we wish for capitalist gains. This is a mindset that we must challenge, and question from where such attitudes originate.

Thanks for your post – this was very thought-provoking and provided some important platforms for discussion.

– Charlotte

Hi!

Thanks for your replies – let me clarify; when I mentioned the lack of understanding I am referring specifically to immigrants rather than the settlers of Canada. While I understand and can sympathize with settlers to a degree I agree that what they did was atrocious and intentional in most if not all cases. But I find when looking at stories of immigrants during the post-World War eras and other booms in cross-Atlantic immigration (including my father, my grandparents and my step family) I find that Indigenous claim to Canada is overlooked by these people simply because it hadn’t been publicized internationally in an appropriate manner.

And I do understand the controversy of using the term ‘profit’. I was attempting to stick with the Hobbit analogy where the dwarves want the literal riches of the mountain. I chose this clip because in only a minute and a half a fantasy story is able to describe some very real conflict that is reflected in our discussions recently and do it in a very moving way (with obvious emotions coming from the music choice and acting). I believe that Indigenous groups can be reflected in the dwarves even if just superficially. The clip I wanted to use mostly for it’s description of home and the fight that the dwarves face in order to reclaim it that reflects a feeling among the Indigenous peoples.

I love this discussion! You’re really making me think deeper about what were just initial thoughts on the topic and general ideas that Chamberlin presented!

Hi everyone, Great discussion and very thought-provoking. I have to admit I’m pretty ignorant of the Indigenous experience, so am really learning a lot from readings, and from discussions like this one.

When I read Chamberlin’s argument for “changing to underlying aboriginal title” (230), I understood it as a way to assert this land as aboriginal ‘home’ land, where what it means to be home is to feel entitled and empowered to act and have a say within that home. I think that while what Chamberlin is suggesting is just a symbolic title change when he says: “Nothing would change if underlying title were aboriginal title. It would be fiction. The facts of life would remain the same. […]And yet of course they would not remain the same, because this new title would constitute a new story and a new society” (231), the symbolism would be deeply empowering, nonetheless. Having visited the Museum of Anthropology recently, not having been for several years, I felt a real sense that the MOA, and a little piece of UBC, was in the process of being taken back by aboriginal people, as I found out that they store and take out masks and other important objects to them at will; the MOA is not just a warehouse for dispossessed things of cultures gone by, but is being used in non-museum-like ways by indigenous peoples because they feel entitled and empowered to do so, through symbolic decolonizing acts like signing that, for example “Haida” are hosting UBC that day. I saw there how symbolism can empower actions which can serve to ‘re-home’ people who have for a very long time been in a kind of exile while never having left their home. I’d love to hear of other examples of symbolic gestures leading to active changes for Canada’s First Nations peoples, and what you think of my definition of ‘home’. Thanks, Claudia