Imagine this.

It’s the Middle Ages, around 500-1500, at dinner time. You’re sitting at the dinner table, surrounded by family. You reach a hand over to grab a small loaf of freshly baked bread; the day has been long and tiring so, as soon as your fingers grasp the warm rye roll, you can feel your stomach grumble with anticipation.

You take a bite, chew, swallow and everything goes downhill.

It’s the Middle Ages, around 500-1500, just past dinner time. You’re hunched over at the dinner table, your family surrounds you with worried looks on their faces. You reach a hand up to your mouth, the half-eaten loaf lays forgotten on the floor. You feel dizzy and your muscles ache; weak in a way that’s different from exhaustion. Before your fingers even touch your face, you can feel your stomach churning with nausea.

Maybe the bread was old? -but it was freshly baked and still warm.

Maybe you caught the flu? -but you don’t get better. In fact, you get worse. You start convulsing, you start hallucinating, your tissues start to die as your blood flow is constricted. Then, after a few frantic attempts to keep you alive, you pass away… along with other members of your village who experienced the exact same thing.

Now, you wouldn’t have known it at that time, but you were a victim of an ergotism epidemic.

What is Ergotism?

Ergotism is a disease caused by ergots, a form of fungi. Often found growing on cereal and forage plants like grass, wheat and rye, ergots can be deadly when ingested.

Throughout history, there have been multiple epidemics of ergotism. With symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, hallucinations, convulsions and gangrene (a condition where your tissues will die from a lack of blood flow), there have been records of ergotism outbreaks and deaths dating back as early as the Middle Ages; maybe even before then.

Because ergots will grow on forage plants such as wheat and rye, they can easily be ingested by a large population as infected crops are fed to livestock and processed into contaminated flour, a common ingredient used in multiple food dishes. For that reason, ergotism has been the cause of death for tens of thousands of people throughout history; a single case in 944 France caused the death of 40 000 people.

‘The Temptation of St Anthony’ (1512-1516) Ergotism depicted by Matthias Grünewald. Source from Wikipedia

Nowadays, however, as the knowledge on ergots advance, there has been fewer reported deaths caused by ergotism and nearly zero ergotism outbreaks within the human population in developed countries. Regulations have been placed on agricultural and milling procedures to prevent ergots from being milled into flour. Furthermore, farming methods such as rotating between growing wheat and rye plants have been devised to reduce ergots from growing on the crops altogether.

It’s been mentioned briefly but…what exactly are ergots again?

Biology of Ergots

Ergots are a life stage of the Claviceps sp. fungi. Claviceps sp. are an obligate biotroph and a plant parasite, which means they have to gain nutrients from another plant in order to survive. While the type of host plant can vary depending on the specific species of Claviceps, the main concern for humans are the Claviceps that grow on cereal and forage plants such as Claviceps pupurea; which often grows on plants like wheat, rye and grass.

Because Claviceps need the presence of a healthy host plant to survive, usually its life cycle will be in tune with the life cycle of the plant. Not to mention, fungi will typically reproduce asexually when environmental conditions are ideal and stable so they can quickly disperse their spores and infect other plants more effectively. When conditions are not ideal, however, fungi will rely on sexual reproduction and may even enter a dormant and toxic phase until conditions are stable again.

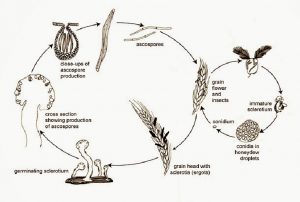

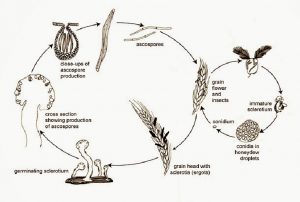

With that said, the life cycle of Claviceps sp. with grass flowers as its host plant might go as follows:

Life cycle of Claviceps pupurea. Source from Plantlet

In early spring, spores called ascospores of the fungus will be blown by the wind until it’s caught on the style of the grass flower. Branching structures called hyphae will grow from the ascospores into the grass’ ovary where it’ll absorb the sugars from the ovary. In spring, conditions are stable and ideal for the fungus, so it’ll reproduce asexually. Claviceps will produce asexual spores called conidia outside of the grass’ ovary. It’ll also produce this sweet “honeydew”-like substance to attract insects that will disperse the conidia and infect other plants.

As long as the conditions remain stable, this cycle of infecting plants, absorbing sugars, producing conidia will continue throughout spring. However, when summer begins, the host plants start to die as the weather gets hot and dry.

As conditions become unstable, the fungi will go dormant and toxic. It will form a dense mass of non-reproductive tissue generally called the sclerotium. For Claviceps, that sclerotium also has another name you might recognize as the ergots. Ergots are the dormant and toxic stage of Claviceps and if ingested, will cause ergotism. Fortunately, ergots in cereal plants differ quite drastically from uninfected grain kernels; not only are they a dark purple-black colour compared to the lighter coloured grains, but they can also grow a lot longer, making it easy to identify the infected grains.

Ergot on rye. Source from Bioweb

From ergots, pin-head-shaped structures called stroma will sprout as conditions start to stabilize in the next spring season. Embedded in the pin-head of the stroma, are the reproductive structures the fungi need to produce ascospores; the spores that infected the plant in the first place. Finally, the ascospores will be shot from the stroma and carried by the wind to infect another host plant where it will continue on the cycle.

Stroma growing out of ergot (sclerotium). Source from Bioweb

With the knowledge of what ergots are and what they can do, it sounds terrifying! …Or is it?

Biotechnology of Ergots

Despite the toxic properties, there have been discovered ways to utilize ergots. The mycotoxins produced by ergots are known as ergot alkaloids and from those mycotoxins, multiple compounds have been derived for human use.

One of the compounds derived is ergotamine; a medicine used to prevent and treat migraines and cluster headaches. Because ergots restrict blood flow, ergotamine works by reducing the extra blood flow to the cranium and therefore reducing the amplitude of the pulsations within the arteries.

Another compound derived is ergometrine, also known as ergonovine; a medicine used to induce labour and stop postpartum bleeding. Similar to ergotamine, ergometrine relies on the properties of ergots that reduce blood flow by narrowing the walls of the blood vessels which, in turn, reduces blood loss postpartum.

Chemical structure of the compound, ergometrine. Source from Wikipedia

With that said, there are risks and side effects to both of these compounds. An overdose of either compound can lead to ergotism and possible side effects of ergometrine include vomiting, headaches and high or low blood pressure. Both these compounds aren’t for daily use and should only be used if prescribed by a medical professional. They’re also heavily regulated; ergometrine especially so due to the fact that it’s also known as a precursor to LSD.

Because of the risks and regulations, the use of ergot-based compounds as medicine is a debatable topic. Some people argue that the safety concerns are far too great to be ignored while others argue that it’s already prevented many deaths from postpartum bleeding.

Now, whether you are against ergot-based medicines or not, it’s fascinating to see how much impact a small fungus, not much longer than a child’s pinky finger, has on our history… and perhaps, our future as well.

– Christine Sun