T he holiday season is often times associated with building a lifetime of memories with friends and family, and to all gather in celebration of another year. However, for Sonia and I, our holidays were spent away from loved ones on the other side of the world, and for justifiable reasons.

he holiday season is often times associated with building a lifetime of memories with friends and family, and to all gather in celebration of another year. However, for Sonia and I, our holidays were spent away from loved ones on the other side of the world, and for justifiable reasons.

From educating children and health professionals about oral health, to providing clinical therapy, and conducting oral cancer screenings, this initiative gave me the opportunity to exercise all aspects of the dental hygiene scope of practice. A moment that stands out, one that I often revisit, is walking through the overcrowded and non-air-cond

itioned Oncology Hospital, seeing beds occupied by two to three patients who are battling advanced stage cancer with tumours the size of a grapefruit. This moment of enlightenment truly provided realization that although dental hygienists are not involved with treating such serious conditions, they play a significant role in the early identification of such complex and fatal oral conditions.

I went into this initiative thinking that coming from North America where resources are abundant and the quality of life is high in comparison to developing countries, I would be able to give back and share the wealth of knowledge I have obtained from my undergraduate program; however, now I feel that I have gained more than I could have ever given. Although the health professionals we were highly educated, they were humble in their knowledge and gave us outstanding respect as we conducted educational sessions. Furthermore, even though oral health professionals working in the university and hospital receive very little salary (~$150USD/month), they worked tirelessly to raise up a new generation professionals and develop a caring relationship with their patients ensuring to deliver the highest quality of care. After a day of work at the university or hospitals, they will work in a private practice until late at night just to make enough money to survive. Seeing them pursue their passion and devote all their energy to their career without any restraints encouraged me to look past the money aspect in my career and strive to make a difference in my community and facilitate the advancement of my profession.

While I continued to develop a deeper appreciation for this profession and explored different practice settings in Vietnam day after day, it has further reaffirmed the significance of my role as an emerging licensed dental professional. I have left Vietnam even more passionate to advocate for preventative services to reduce the prevalence of oral diseases, increased access to healthcare services, and increase awareness.

https://youtu.be/XjcllsNFxX0

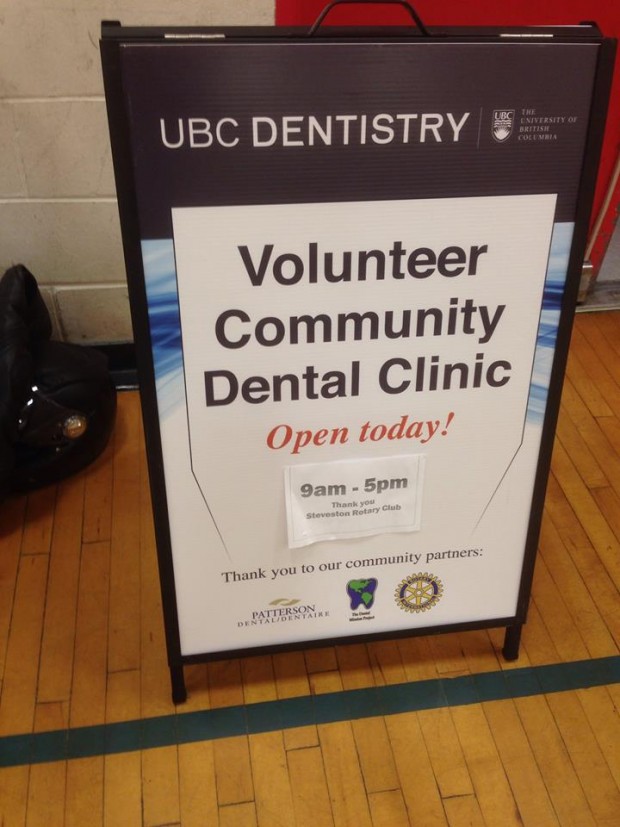

y, homelessness and addictions. The Orchard is a subsidized housing complex with 75 town homes, aimed to provide long and short term housing to new immigrants, refugees and low socioeconomic individuals. Similarly to Pioneer Community Living association, my role as a student dental hygienist was to provide preventative and non invasive therapeutic services such as dental hygiene exams, oral cancer screenings, debridement, fluoride administration and oral health instruction. Although the majority of clients are individuals living in the Orchard complex, we recruited new clients through the community health nurse, referrals from current clients and from a local church that is sponsoring two Syrian refugee families that arrived in February. At this community site, three dental chairs and two portable dental units were shared between four students.

y, homelessness and addictions. The Orchard is a subsidized housing complex with 75 town homes, aimed to provide long and short term housing to new immigrants, refugees and low socioeconomic individuals. Similarly to Pioneer Community Living association, my role as a student dental hygienist was to provide preventative and non invasive therapeutic services such as dental hygiene exams, oral cancer screenings, debridement, fluoride administration and oral health instruction. Although the majority of clients are individuals living in the Orchard complex, we recruited new clients through the community health nurse, referrals from current clients and from a local church that is sponsoring two Syrian refugee families that arrived in February. At this community site, three dental chairs and two portable dental units were shared between four students.

![IMG_2010[1]](https://blogs.ubc.ca/dhwithdelwyn/files/2016/04/IMG_20101.jpg)

![IMG_2038[1]](https://blogs.ubc.ca/dhwithdelwyn/files/2016/04/IMG_20381.jpg)

he holiday season is often times associated with building a lifetime of memories with friends and family, and to all gather in celebration of another year. However, for Sonia and I, our holidays were spent away from loved ones on the other side of the world, and for justifiable reasons.

he holiday season is often times associated with building a lifetime of memories with friends and family, and to all gather in celebration of another year. However, for Sonia and I, our holidays were spent away from loved ones on the other side of the world, and for justifiable reasons.

Mental illness is becoming increasing prevalent in Canada as statistics reveal that in any given year one in five Canadians experiences a mental health problem.1 Additionally, literature shows that people are more likely to visit their oral healthcare providers on a regular basis than their other primary healthcare providers.2 It is reported that adults aged 20-44 rarely visit their family doctors for preventive care, yet they visit their oral healthcare professionals at least once a year.2 Therefore, understanding this population`s barriers to oral health care can help clinicians managed this population and treat them with dignity they deserve. In addition to providing clinical services, my team and I held a table clinic to educate the population about the difference between healthy and unhealthy gums and showed them how to care for their oral health daily. The goal of the table clinic was to encourage the population to equip them with the basic knowledge and skills to care for their oral health daily.

Mental illness is becoming increasing prevalent in Canada as statistics reveal that in any given year one in five Canadians experiences a mental health problem.1 Additionally, literature shows that people are more likely to visit their oral healthcare providers on a regular basis than their other primary healthcare providers.2 It is reported that adults aged 20-44 rarely visit their family doctors for preventive care, yet they visit their oral healthcare professionals at least once a year.2 Therefore, understanding this population`s barriers to oral health care can help clinicians managed this population and treat them with dignity they deserve. In addition to providing clinical services, my team and I held a table clinic to educate the population about the difference between healthy and unhealthy gums and showed them how to care for their oral health daily. The goal of the table clinic was to encourage the population to equip them with the basic knowledge and skills to care for their oral health daily.