For my second lecture observation this term I attended EOSC 114 – The Catastrophic Earth: Natural Disasters. In contrast to the first lecture I observed, EOSC 114 is a high-enrolment course with over 300 students in each section. It tends to be taken by a lot of upper-year students as part of the science requirement for their degree, but also by first-year students that want to major in geology. As such, there is a wide variety of students in the course and that can present challenges for the instructors. Another unique feature of EOSC 114 is that each of the seven modules is taught by a different instructor, generally one that specializes in that field. My mentor is currently teaching the Landslides module of the course, but he also taught the introductory module so he had worked with the students before. He mentioned that this makes it harder to get students to participate in the class since they are constantly having to adapt to a different teaching style.

There were several things that the instructor did during the lesson that I think are good techniques, especially for large classes, and that I would like to try out in my own lessons. Before the class had even started he played a YouTube video of a landslide that was narrated by a “landslide chaser”. Most students didn’t pay attention to the whole video since class hadn’t started yet but I think that it was still beneficial for them even if they only ended up watching a small portion of the video. Students would have benefited by seeing a landslide and they likely picked up on some features of landslides regardless of how long they were watching the video. It was also a good way to introduce the new module, since this was the first lecture on landslides, and to get students excited about the topic.

The instructor posts pre-lecture slides on Connect that don’t include clicker questions and any other information that relates to activities or mini assessments that will occur in class. This is a great way to give students lecture slides, which they so often ask for, without giving away the answers to questions that will be asked during the lecture. The slides are then updated to post-lecture slides after the class but without the answers to the clicker questions to encourage students to come to class.

The learning goals were listed on one of the first slides but the instructor didn’t read out the goals during class since. The reason for this is that students won’t listen to something being read off a slide, so they can just be included and students can refer back to them later. The instructor instead reminded students that they should be referring to the learning goals when studying and that the midterm and final exam questions will be based on material that is covered by the learning goals.

The hook used in this lesson was to ask students what their experience with landslides was using a clicker question. Two of the options were to have been in or very close to a landslide. The instructor asked for students that chose these answers to share their landslide story with the class. This would have been a really great hook into the lesson but the instructor forgot to repeat what students had said, so from my place in the back of the lecture hall I couldn’t hear what the student was saying. I mentioned this to my mentor after his lecture and he was disappointed that he had forgotten to do this, since he knew that it’s very important to repeat everything students say in class to make sure that everyone has heard them. He said that he’s given students a microphone in the past but found that once students realized they would have to talk into a mic they didn’t want to share their stories.

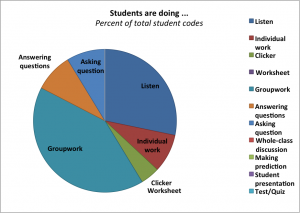

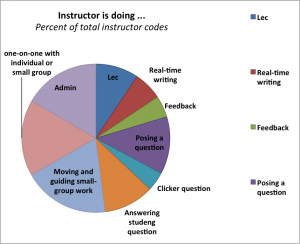

Another technique the instructor used is that every time he asked a clicker question during the lesson, he did it in a series of steps. First the students answered on their own without discussing the question with anyone around them, then the instructor would look at the results, tell them that they were split between answers, and to “turn to your neighbour and convince them that you’re right”. Even though doing clicker questions this way takes a bit more time, it is infinitely more valuable because students are learning a lot more by teaching each other. It also gets them to think critically about why they chose the answer they did. If clicker questions are constantly done in this way students will learn to put more thought into their answer instead of choosing an answer arbitrarily since they know they’ll have to explain their reasoning. Once the students voted again the instructor asked for someone to share why they chose their answer. In one case the student that answered ended up having the wrong answer. The instructor reminded students that he wants them to be wrong in class because they will better retain the material if they were wrong. I think this is important to emphasize to avoid embarrassing students if they give the wrong answer after they have worked up the courage to share in front of the whole class. It will also make them more comfortable answering questions since they’re reassured that it’s okay to have the wrong answer.

The instructor showed one video in class of a landslide to get students to notice features of the slide that they would later be able to use as clues to identify the type of slide. He played the video twice because it’s very difficult to notice specific details of something when you’re seeing it for the first time. Then he asked the class to share some important features of the video, without telling them what these features could indicate about the slide. Identifying landslide types would come later in the class. To get the class to participate, he asked for someone in the back of the room to answer the question, and then used the stare and wait tactic until someone answered. I think this tactic would be very useful in large classrooms because it’s harder to single someone out when you don’t know the names of all the students in the class. It’s also less intimidating to give students the opportunity to volunteer to answer a question rather than selecting someone that may feel very uncomfortable answering.

The class ended with an activity in which students learned to identify different types of landslides based on their unique features that they identified in pictures. There were six pictures, three of which were completed in class and the other three were posted on Connect for homework. Students were provided with a simple worksheet that included space to identify the material type, detachment surface, rate of movement, and name the landslide in each of the pictures. The instructor then told the students to pair up and showed the images on the PowerPoint slide.

The final thing I took away from this lecture is a good technique for creating lecture slides. The slides the instructor used were very simple with black text, a white background, and sans serif font. In our meeting after the lecture I learned that this style is the universal design for learning, meaning that it is most accessible for students that have a visual impairment because it provides the highest contrast and the most simple font. I’ve often felt the need to make slides that are visually appealing, meaning slides that are colourful, have some sort of design, and sometimes have simple animations to break up areas with more text. I found it interesting that this makes it harder for students that are visually impaired to read the slides and that it may be distracting for other students. The idea of using simple black and white slides also appeals to me because they’re a lot less work for the instructor to put together.