(Photo: self)

(Photo: self)

4] In the last lesson I ask some of you, “what is your first response to Robinson’s story about the white and black twins in context with our course theme of investigating intersections where story and literature meet.” I asked, what do you make of this “stolen piece of paper”? Now that we have contextualized that story with some historical narratives and explored ideas about questions of authenticity and the necessity to “get the story right” – how have your insights into that story changed?

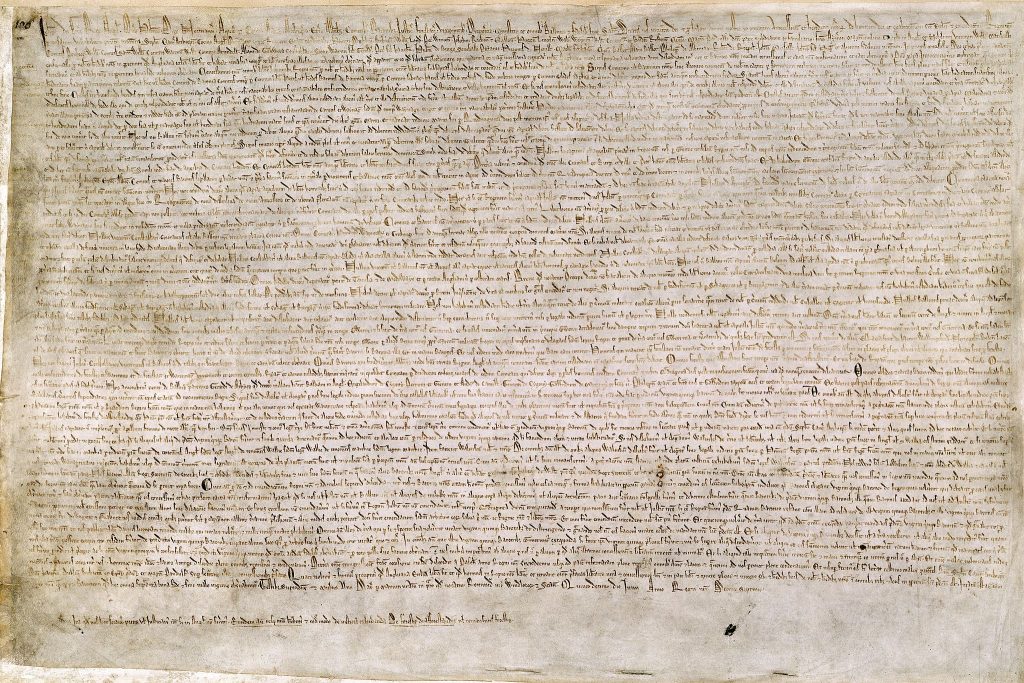

The Coyote not only travels through time, he also travels far – all the way to England. Harry Robinson narrates the meeting of the two kings to make law for their children and to avoid war (Robinson 70-74). The Coyote negotiates the books to be kept until his children grow up, and learn to read and write (Robinson 79-80). This is a story that gets to the bottom of things. This is a story of whose paper, whose laws, and whose chapter in history? It contests the notion of a new Eden with a frozen people awaiting for the arrival of the European settlers. It raises questions such as who is Chapter One and who is Chapter 15 (Asch 2-3).

Looking at the first Coyote story with new lenses from the course is a rewarding experience.

Firstly, it comes back to origin. A common one, according to the story. Even if the children of paper thief are misbehaving, the First Nation narrator does not call for their eviction; rather, he is asking for the right to exist and co-exist in peace. There is kindness to be found in that claim. It also asserts on the origin of the laws and rights. In the belief system First Nation rights are not a concession or gift from the European settlers – they are inherited from ancestors. The mechanics of inheriting the same may be beyond European understanding, that is, in a collective, cumulative, and spiritual way (Carlson 60). This is helpful in investigating First Nation rights, such as ones enjoyed by those on reserves.

Secondly, what is authenticity? Is only history written down with references authentic? It has been the prevailing attitude. A B.C. justice, before even touching on authenticity, has dismissed the pre-contact history of a First Nation community as “… [n]asty, brutal, and short” (Asch 11). There is also a sentiment post-contact elements taint First Nation narratives and diminish their authenticity. That notion puts First Nation storytellers in a difficult place, and with albatrosses around their necks (King 185). Is the Coyote story tainted and less believable because it contains contemporary elements? From the Salish point of view, this is a moot point. The concept of time is simply different, and the stories could be a contemporary understanding of what is going in the world, derived from historically accurate narratives (Carlson 56-7). I would not dismiss the Coyote story as unauthentic due the mention of a female English monarch or colonization, etc. Rather, as it does not truly position the European settlers as the Other; it provides non-judgmental access to the First Nation response to the world (King 189).

This bring us to the final point, getting the story right. The Salish people hold strong convictions on the existence and importance an animate non-human sphere, with spirits who can interfere with worldly affairs and fortune (Kew). This is an essential element to authenticity, since telling stories inaccurately or with omissions will result in dire consequences coming from the spiritual realm (Carlson 57-8). This practice of extracting stories correctly and their entirety from memory being a spiritual requirement establishes authenticity to some degree; comparable to a witness taking an oath with a hand on the Bible before testifying in European traditions.

That is “Black and White”, according to the second Coyote story, as to the books and the laws of their people (Robinson 85). It ends with a mention to land. Do the Coyote stories tell you who is entitled to be on the land, according to what and whose law, and how are those laws deemed reliable? What do you make of the stories of the Coyote at a historical and geographical intersection?

Works Cited

Asch, Michael. “Canadian Sovereignty and Universal History.” Storied Communities: Narratives of Contact and Arrival in Constituting Political Community. Ed. Rebecca Johnson, and Jeremy Webber Hester Lessard. Vancouver: U of British Columbia P, 2011. 29 – 39. Web. 21 Jun. 2016.

Carlson, Keith Thor. “Orality and Literacy: The ‘Black and White’ of Salish History.” Orality & Literacy: Reflections Across Disciplines. Ed. Carlson, Kristina Fagna, & Natalia Khamemko-Frieson. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2011. 43-72. Web. 21 Jun. 2016.

Hanson, Erin. “Reserves.” First Nations & Indigenous Studies, the University of British Columbia, 2009. Web. 22 Jun. 2016.

King, Thomas. “Godzilla vs. Post-Colonial.” Unhomely States: Theorizing English-Canadian Postcolonialism. Mississauga, ON: Broadview, 2004. 183- 190. Web. 21 Jun. 2016.

Kew, Michael. “Indigenous People: Northwest Coast.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada: Mar. 04 2015. Web. 22 Jun. 2016.

Robinson, Harry. “Coyote Makes a Deal with the King Of England.” Living by Stories: a Journey of Landscape and Memory. Ed. Wendy Wickwire. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2005. 64-85. Print.