- “If Europeans were not from the land of the dead, or the sky, alternative explanations which were consistent with indigenous cosmologies quickly developed” (“First Contact” 43). Robinson gives us one of those alternative explanations in his stories about how Coyote’s twin brother stole the “written document” and when he denied stealing the paper, he was “banished to a distant land across a large body of water” (9). We are going to return to this story, but for now – what is your first response to this story? In context with our course theme of investigating intersections where story and literature meet, what do you make of this stolen piece of paper? This is an open-ended question and you should feel free to explore your first thoughts.

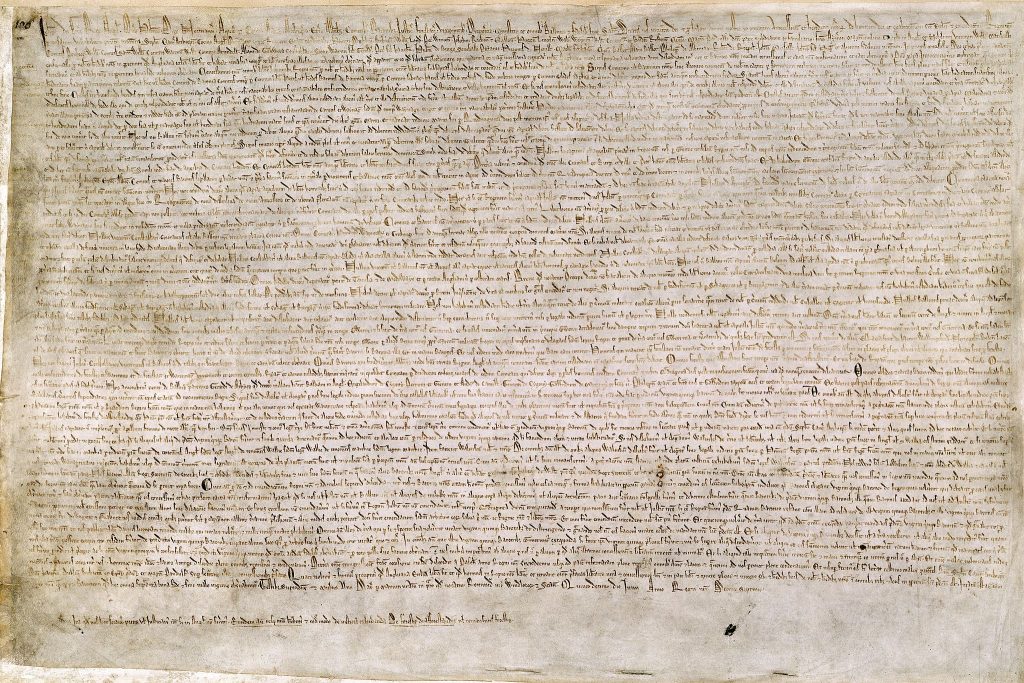

(The barons and King John of England. Wiki Commons Licence.)

Listening to and reading stories are enjoyable to inquisitive minds. Especially when such stories present new possibilities and new worlds. Some contact stories in North America can be read as a role reversal. The Europeans arrive with their scientific achievements, expectations, and preconceptions, knowing exactly what they will encounter (Lutz 3). On the other hand, First Nation narratives, while they do not travel as far, are not passive; they can be fluid and adaptive.

The Coyote story is rich in many folds. At first there is a striking similarity to a European narrative: an entity is given a sole command by a higher power, disobeys it, and faces consequences. Is this story a product of cultural interaction, or is this a common theme in most human societies? The tendency of humanity to have something good and then manages to screw it up entirely? That the world is perfect but not immutable?

The storyteller then takes us rosier grounds for a bit. Though banished, the children of the younger brother will one day return as family. There, foreknowledge and forgiveness. The sinner finally comes home. But where is the redemption? Turns out the evil brother’s descendants will behave badly and there is a dispute over the piece of paper. Uh, paper! Laws, titles, “civilization”.

Are all important things ought to be on paper? We have looked into orality in a previous section, and here it is again. In this story the importance of paper is somewhat recognized, ironically, in spoken story. That piece of paper remain important in the plot. Nevertheless, the children of the righteous brother are now entitled to laws against the children of the evil brother. The Coyote will visit England and strike a deal with their monarch. This crux is another role reversal – European settlers being subject to the laws of the First Nations. The laws of those expecting from the shore not “the other”, but rather family coming home.

My first response to the story is how relevant it is. It touches on historical wrongs, politics, and First Nation rights. The story does not live in a frozen, prehistoric past; it is definitely not “cold” (Wickwire 22). The story is clever like a coyote and hard to decipher – put down our European-influenced lens and see an exact mirror image. Dig in deeper and we will see a fixation, which is land. European law tends to govern the law as to who may possess, occupy, and benefit from it. If a certain people have fostered strong ties with the animals, the water, and the land: their perspective would be quite different. They are with the land, but they do not govern it. They have not industrialized. That is, taking more than one can reasonably need, and feeling awfully good about the commercial gains. Rather they live with, understand, and try to be at harmony with it. The laws are from the land to the peoples, not vice versa.

What is your take? I really look forward to your feedback.

Works Cited

Burgesse, Michael. Illustration for Book 12 of Paradise Lost. Christ College, University of Cambridge, 3 Feb. 2014. Web. 15 Jun. 2016.

Lutz, John. “Introduction.” Contact Over and Over Again.” Myth and Memory: Rethinking Stories of Indigenous- European Contact. Vancouver: U of British Columbia P, 2007. Web. 13 Jun. 2016.

“Part II: Right of The Aboriginal Peoples of Canada.” Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1982. Department of Justice, Government of Canada, 3 Jun. 2016. Web. 15 Jun. 2016.

Wickwire, Wendy. “Introduction.” Living by Stories: a Journey of Landscape and Memory. Harry Robinson. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2005. Print.

Hi John,

Great job on the blog.

In regards to your first response on the story, your point about ‘European law’ in relation to the dichotomy in the perception of law through fostering strong ties with animals, water and land really made me think deeply about the power relations and the discrimination faced by the indigenous people as it pertains to their land rights and preservation of their cultural beliefs/values.

My question for you is what do you mean when you state the “the laws are from the land to the peoples” ? In reading that statement, I am lead to believe that the power of the ‘laws’ as it pertains to land ownership are less meaningful because the laws are created by the land, and not the people. This statement was thought provoking and my questions aims to clear up the meaning of your statement.

Awesome work John, all the best.

Deepak Nijjer.

Hi Deepak,

Thanks for your thought-provoking question.

By “the laws are from the land to the peoples”, I mean to indicate the direction of logic and the source of the rules. The West or the global North have learned there are certain natural rules that humans cannot change; e.g. over fish in a body of water and the stock will be gone over time, therefore we should fish responsibly. That is the logic I’m alluding to.

To dig a little deeper, the imagined ownership of land is a laughable attempt to address certain human insecurities. In Canada it is possible to own land in perpetuity (and pass the title to heirs and assigns). Does that make our lives, let us say they span 100 years, a little more perpetual compared to the lifespan of this planet?

– John

Thank you John for your analysis of Robinson’s story about the twins. I enjoyed your many questions, and they made me think. When I first read Robinson’s story, I did not see a similarity to a European narrative, but after you wrote this, I could see a connection. My first question for you is, what specific narrative are you referring to? (I have my own ideas, but I would like you to confirm them.)

I noticed you did not refer in your discourse to any mention about the original theft of the paper. Although you did mention how the overall story touches on historical wrong doings. I also responded to this same question, and I too did not address this issue of theft. Instead I focused more on how the Europeans used written language and laws to justify their actions. My second question for you is, do you think this story, of how one twin stole the paper, speaks directly to the theft of Native lands, or do you think it has a deeper meaning. If so what do you think that is?

I look forward to your response.

Linda

(As a side note, if (in WordPress) you activate the plugin: Subscribe to Comments Reloaded 160115 (which can be found under plugins) then when people make comments, they can subscribe to be notified when the comments are responded to 🙂

Hi Linda,

Thanks for your excellent questions and the tip on the plugin (activated).

In regards to your first question, I was alluding to European narratives and attitudes. Specifically, the narrative of the fall of humanity: Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, a sole command to not eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge, we all know take happens then. I also refer to the attitude of human ownership or lordship over the land. The sentiment that this planet is for our taking and exploitation. In some cases this attitude is justified by the Christian lens, e.g. “And you, be ye fruitful, and multiply; bring forth abundantly in the earth, and multiply therein” (Gen. 9:7). (The Bible also tells stories on loving thy neighbour, and the sinless person may judge the sinful and throw the first stone – I am not saying more tradition is less benign than others.)

Coming to your second question – not directly. I think what has been stolen in the Coyote story is right to exist and co-exist in peace. The evil brother’s children are still family in the narrative; and that is an olive branch (sorry, another European analogy), not an attempt to send them home. I am not entirely certain about this interpretation, and look forward to your thoughts!

– John

Thank you for your responses to my questions. I had thought you were alluding to the Garden of Eden. As to the left of the document, I love your comment about the right to exist and co-exist in peace has been stolen. I hadn’t thought this far out, I was only thinking strictly of the material items in questions, but I agree with you. Through the actions of the Government of Canada regarding Residential Schools, not only has the culture, and language been stolen from the First Nations People, but their right to exist as themselves has been stolen.

Thanks for the additional insight

Linda

When I did my reading of this story I was focused on the paper as a means of communication and didn’t look too deep into the notion of it as pertaining to land ownership. It was a great analysis! Especially considering that that has been an issue that receives a lot of the focus in contemporary society. When talking about the paper as a ‘written law’ document I think that the story takes on different meaning. Because Wickwire does mention that at Potlatchs between different tribes enabled them to tell stories that established laws and rules as well as ownership. These stories made decisions and allowed discussion and my impression is that as those occurred, more stories would form and old stories would be updated. It was the banning of these stories through the residential school system that hindered the people so much because their way of establishing ownership and the like was undermined and lost.

I wonder, however, how the brothers in the story represent this dichotomy. The brother who takes the paper when he was warned not to is banished, but this isn’t exactly punishment but rather time for him to think and return to his other brother when he is ready.

What are your thoughts on the brothers and their reunification through their ancestors?

Hi Charlotte,

Thanks for your comments on ceremony and the Coyote story. I am in agreement with you – the banishment is not punishment, or at least not a harsh one. I think the reunification offers a collective sense of forgiveness. It gives us a First Nation lens on the arrival of the Europeans and their laws; and quite a kind one, the settlers are not “the other” but people from a common origin.

I would love to hear your reading of the story too!

– John

Thanks for the post John. Having “strong ties with the animals, the water and the land,” the Native communities see that they are part of the land. The Europeans who think they can possess and take advantage of the land may have simply fooled themselves. Perhaps the Natives do not just operate at the other end of the spectrum, but rather recognize that they can’t escape the laws that govern the land whether people acknowledge the situation or not. They probably see themselves as intimately connected to nature in the way of being a cog in a wheel. In this sense, could they have seen that the European colonizers are setting up their own misfortune by exploiting the very source that supports their life?

Cheers,

Lorraine

Hi Lorraine,

Thanks for your remarks.

I think so – the industrial revolution might be a doom to our species. It is based on greed, not need. In relation to the land, it has become a tool to generate revenue rather than sustain life. While we have made advances in science, commerce, and technology, it would be quite foolish to think that translates to we have it all figured out.

The misfortune would be ours instead that of the land. I do not think we are capable of destroying the resilient land, but we are quite capable to mutate it to the extent we can no longer survive on it.

What do you think?

– John

Hi John,

I thought a lot of the points you touched on in your closing paragraph were very important to the overall discussion of this course. You pointed out, without using the specific terminology, that European culture is based around competition, and their laws put them over governance and possession of the land. The Native peoples, on the other hand, base their culture on cooperation, right down to having laws created because of/from the land, as opposed to over it. Its not surprising that these cultures and views are also reflected in the stories of each. I really enjoyed how you tied this together.

I look forward to any comments from you,

Gillian

Hi Gillian,

Thanks for your observation.

Yes, it is competition vs. collectivity. It is a culture of dictating who is entitled to be where in contact with one that tries to co-exist in peace. The former is still, if not more prevalent today, e.g. barriers on park benches and fountains that go off at the middle of the night to prevent people from sleeping in public spaces.

– John