(Painting James Gilchrist Swan, Public domain.)

2] In this lesson I say that it should be clear that the discourse on nationalism is also about ethnicity and ideologies of “race.” If you trace the historical overview of nationalism in Canada in the CanLit guide, you will find many examples of state legislation and policies that excluded and discriminated against certain peoples based on ideas about racial inferiority and capacities to assimilate. – and in turn, state legislation and policies that worked to try to rectify early policies of exclusion and racial discrimination. As the guide points out, the nation is an imagined community, whereas the state is a “governed group of people.” For this blog assignment, I would like you to research and summarize one of the state or governing activities, such as The Royal Proclamation 1763, the Indian Act 1876, Immigration Act 1910, or the Multiculturalism Act 1989 – you choose the legislation or policy or commission you find most interesting. Write a blog about your findings and in your conclusion comment on whether or not your findings support Coleman’s argument about the project of white civility.

Reading historical legislation is almost a form of time travel, it takes us into the minds of people back then, as to how they have viewed the world. The Indian Act 1876 of Canada gives us a peculiar view into definitions that leads to nation building in the backdrop of bountiful nature and seemingly quiet First Nation peoples. This article will commence with a focus on legal definitions as our telescope into early Canadian First Nation relations. An interesting example being for the purpose of this piece of legislation, a person is defined as “…an individual other than an Indian” (An Act to amend and consolidate the laws respecting Indians 3). If a First Nation man or woman is not a person, then what are they? From reading the Indian Act, a person is a suggested to be Christian and civilized, and there is a mechanism of “enfranchisement” for a First Nation man or married woman to become a fuller member of Canadian society, by satisfying government agents of his or her civility, or earning certain university degrees (An Act to amend and consolidate the laws respecting Indians 26-7). This seems like a system imposed by groups self-prescribed as civilized and superior over the existing inhabitants of the land, and to be fair, offer those inhabitants a way to become “honorary white”.

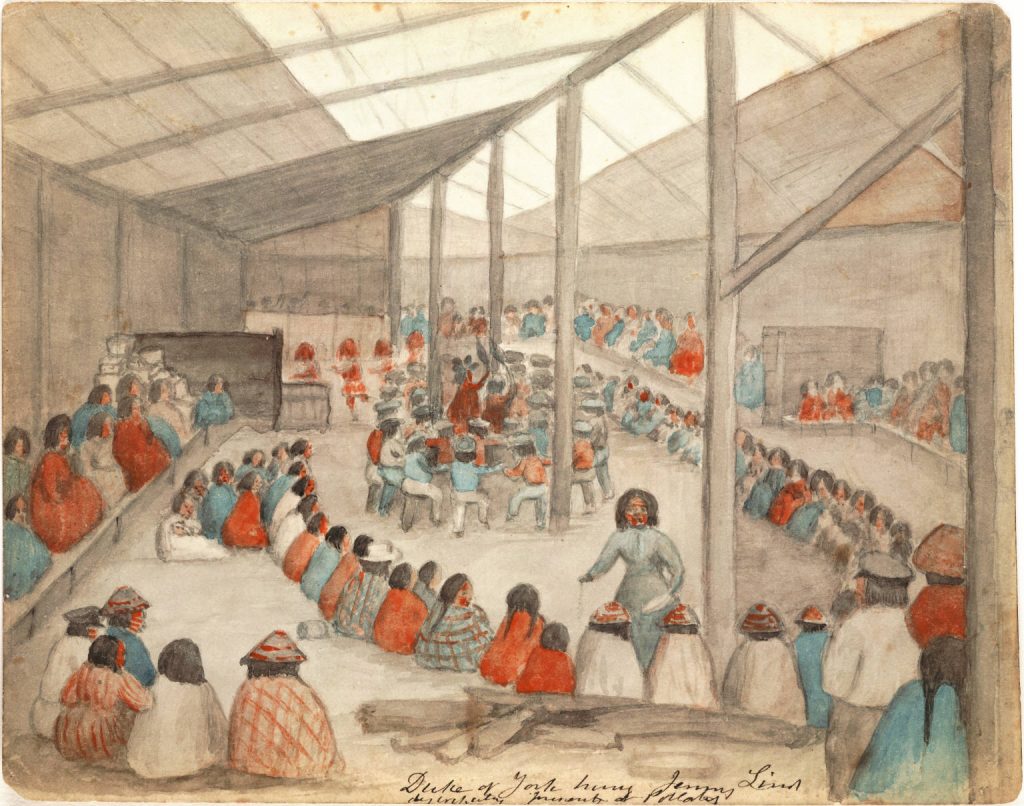

In a way these elements of the legislation fits Coleman’s analysis of civility, that the same is imagined and produced. The production on the other side however, is banned. In court cases pertaining First Nation claims and rights it has been important to define what is acceptable as pre-European political society, and descendants of members of such societies possess traditional rights. This tool of analysis on its own is fine, what is problematic the early legislators have had the historical foresight to make an essential component of political society, gatherings such as the Potlatch unlawful, and thus killing the societies at that generation (The Indian Act).

If nationalism is the product of collective imagination, then the creation of the Canadian nation has been nightmare for those who got in the way. It would be simplistic to point a finger at yell “historic wrong”. What took place was wrong, no question. Understanding what happened and why would be more helpful, and what is why early contact stories are so valuable. Those accounts tell us why and how superiority has been constructed and made permissible, and how it has been acceptable within the civil society of the day. On the other side, stories lead us to understand First Nation societies operate, what we may learn from them and how could we help in their full restoration.

Works Cited

“An Act to amend and consolidate the laws respecting Indians.” Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, Government of Canada: 15 Sep. 2010. Web. 07 Jul. 2016.

“The Indian Act.” First Nations and Indigenous Studies, UBC: 2009. Web. 07 Jul. 2016.

Hi John,

I really enjoyed your post! The definitions of “a person” and “an Indian” that you highlighted are indeed startling. What I find most horrific is the method in which the people affected by the Indian Act of 1876 have an identity forced upon them by the state. We are lucky enough to be able to decide our own identities – I can choose to identify as a Canadian, or as a Vancouverite, or as a student, or as all of these – but the Indigenous peoples in the 19th Century didn’t have this luxury. The Canadian Government forced an Identity upon them, as either a person or an Indian; a ridiculous dichotomy made even more absurd by the way in which individuals could lose their ‘Indian identity’ by marrying a certain person or moving off reserve. I can only imagine the practical and psychological implications of having no control over your own identity…

Cam

Hi Cam,

Thanks for your insights. You’re right – there is a dichotomy. “Indian” status is forced upon the First Nation peoples, and there is also a bar to maintain the same. It can be confusing? Is the government trying to protect First Nation identities or planning the reduction of numbers of status “Indians”? On a deeper level, that is the power of imagination. I tend to associate the word with nice, beautiful thing, but on the other side of the coin, malicious things can come from imagination too.

– John

Hi John, thanks for the in depth post about the Indian Act. I chose the same question, but wrote on the 1910 Immigration Act., so it’s interesting to see the comparisons between the two.

I like how you make the distinction for what is determined as a person in Canada at that time. I agree with Cam when he says that it’s a startling concept to see a person defined as “…an individual other than an Indian.” And with that distinction, we can move forward and talk about how to ‘fix’ that in a way, and I think you’re on the right track with stories. There has been way too much history accounted for that tracks what white people have done to Natives. Taking that step to listen and understand Aboriginal storytellers gives the underrepresented more power, and might help to shift that uneven balance the government has tipped.

Hi Ashley,

Thanks for your response. Yes stories are potent products of history and imagination. I think the very first step to “fixing” historical wrongs is to listen to the stories and respect them. That very first step would position the storytellers as equal and full members of society and fellow inhabitants of this earth (and without the “person” non-sense). These stories will take us to the intersection with literature, and I’m starting to believe those things construct our worlds.

– John

I like that you described Natives as ‘quiet’ in relation to the Indian Act because it brings to light the fact that Native voices were not represented in the writing of the document. You also made some amazing points about collective imaginations too! But how do you think the Indian Act left a mark on Canadian society for other non-whites to be a part of Canadian society? Or does the Indian Act solely affect Natives?

Hi Charlotte,

Very interesting question – thank you. I think it affects the Canadian identity. If we’d like to see today’s Canada as a generally just and peaceful society, then we ought to address historical wrongs, to the extent possible. In that sense, the displacement and repression affect all members of the polity, not just First Nations. It is a “the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing” scenario (Edmund Burke).

– John

Thanks for your post John. Nations being built upon collective imagination are seen across the globe, so those who have not submitted to the ‘nation’ never do get it easy. There are those that do not support the idea of a nation as it only promotes segregation for humanity and there are also those that identify as a separate group or have others label them as a separate group. Nowadays, Canadian academics appear to be finding a way to help restore the damage done to First Nation culture and the government has also somewhat compensated monetarily, but their culture/ land can never be fully restored to its previous state. Do you perhaps think that as long as people continue to think in terms of us and them, harmony can never be realized? Looking at the aggressors and the victims in the world stage, even if the aggressor has apologized and compensated, the grudge toward them never really ceases. And some nations who have never apologized for their atrocities are more revered as their past wrongdoings are, in fact, mostly forgotten. The victims, after a few generations, pretty much just identify as a member of the nation too. As it has happened with many other nations, this must have been the original intent of the colonizers of Canada, even though things did not go according to plan.

Cheers,

Lorraine

Hi John,

I never considered historical legislation as a form of time travel – I find that such an interesting concept! It’s horrifying how an Indian was defined and forced into such a strict box. I agree with Cam that non-Indigenous people – or should I say White people – have the ability to be a Canadian, Vancouverite, or define themselves by their occupation, but for non-white people, it is incredibly difficult to define yourself as anything other than the race that you appear as. The Indian Act of 1876 was created a long, long time ago, but do you still think there are traces of these laws in our current society despite how “progressive” Canada claims to be?

Hi Samantha,

Big question! 😉

I think we’ve made a long way since 1876, but yes, there are traces of historic and systematic measures. Abuse and mistreatment do not simply go away. E.g. former Aboriginal residential school pupils are more likely to have mental health, addiction, and general life issues. That is why reconciliation is not a shiny apple on the shelf; it is a goal that requires political will, public effort, and patience bear fruit.

Thanks for your comments.

– John