The Morris and Helen Belkin art gallery situated on the Vancouver campus of UBC, on unceded Musqueam territory, is hosting an exhibition named Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools to portray and depict the experiences of Canada’s First Nations people during the time of residential schools. In honour of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, it was a popular destination on September 18th (it runs until December 1st) and many students took the cancellation of classes as a great opportunity to visit and explore the exhibit.

The name Witnesses is an interesting concept because it tells us that in some way we, Canadian citizens, residents or visitors, are all witnesses to the era of residential schools. The artists are from all over British Columbia and Canada; some experienced life in the schools while others just remark on the aftermath and resulting effects on society since their complete closure in 1996. As visitors to the gallery, we witness the often repressed expression of First Nations artists.

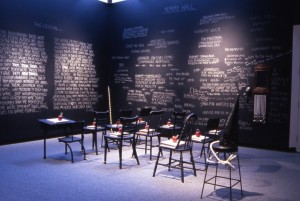

For me, as a non-Canadian, the event was particularly interesting because most things were new concepts. For example, an installation piece named The Lesson by Joane Cardinal Schubert (pictured at bottom) was striking in many ways. The piece is a classroom set up with small, old-fashioned wooden school chairs, painted black and tied together at the legs with rope. On each chair there is a rotting red apple. The walls are painted as black chalk boards and written across them is partly a lesson in the form of a story from within a residential school and partly names, quotes, messages, signatures and cries for help by different people. The concept of the piece is interesting, because unlike someof the art work in the exhibition, it does not immediately scream horror and oppression. Instead there is an eerie sense of entrapment which enables the audience to understand the mind frame of the children in residential schools and the First Nations people as a whole in a colonised land. We are reminded, or perhaps told for the first time, about how the residential school system has had a generational effect throughout Canada by the scrawls on the blackboard, asking ‘Why?’ and lamenting for lost children. The bareness of the classroom is ghostly – this grave era of very recent history still looms over all of us today. Either we are victims, perpetrators or witnesses of these events.

In contrast to the stillness is Lisa Jackson’s video Savage in which a young First Nations girl is portrayed being removed from her mother and taken to a residential school. The students, with zombie-like grey faces, suddenly perform a dance while the teacher is absent. The mother at home is singing which turns into a wail of sadness and frustration at the loss of her daughter to the residential school system. The dancing and singing, to me, symbolise a form of expression and release which has been noted as common in many colonised and oppressed cultures across the world. Often, when everything is taken from you, all you have left is your own culture and it is important to keep it alive with mediums such as song, dance, art and story-telling. The video is a clever contemporary medium that people of today can relate to and helps a naive audience, uneducated about First Nations art and culture like myself, to break the preconceived notion that the First Nations people are behind the times and reminds us that traditional is not synonymous with out-dated. The modern-ness of the video, filmed in such crisp, clear quality, with quirky sound, lighting, music and direction enables viewers to see he First Nations people as equals on the world stage of film and media, especially when we learn, as I only just did, that a film festival in Toronto celebrating First Nations films (the imagineNATIVE Festival) is reaching its tenth year. Savage was presented there in 2009.

Film as a medium is so often associated with Hollywood, the West and America that we begin to merge the idea of ‘film’ and ‘movie’ and forget that they are two very different things – one has become a global sensation that dangerously affects the views, actions and ideologies of people all over the globe while the other is an art form that often documents or symbolises realities such as the despicable treatment of First Nations people in history and today.

Like the video by Lisa Jackson, most pieces in this exhibition are a scary reminder of how ignorant and closed-minded we, as outsiders to First Nations communities, can be. The content of the work is unimaginably varied from religion, to treatment of children, to living conditions, to post-residential school effects and the format of the work was amazingly diverse. Aside from the aforementioned film and installation pieces, works also include sculpture, photography, audio, water colour paint, acrylic paint, print, stone, text, drawing and mixed media. The exhibition has such variety of pieces that everyone can find at least one thing that captures them. Even if you are not usually interested by art, this exhibition will completely broaden your horizons and open your mind to the amazing depths of artistic talent and creativity present in First Nations communities. It will sadden you, yes, and some pieces may horrify you, but that is only testament to the genius of the artists and curators at the Belkin Art Gallery. You will leave more enlightened, open-minded and knowledgeable than you arrived.

The show runs until December 1st 2013, don’t miss it!

- The Lesson by Cardinal Shubert