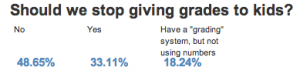

Report cards are a particular example of reporting evaluation results ~ telling students and their parents how well they are doing at what they are supposed to be learning. Typically, report cards are done three times in a school year and this time of year is about when that first report card comes home. I did a Q & A about report cards, and had this to say:

A UBC education expert explains why rewarding good grades is an automatic fail

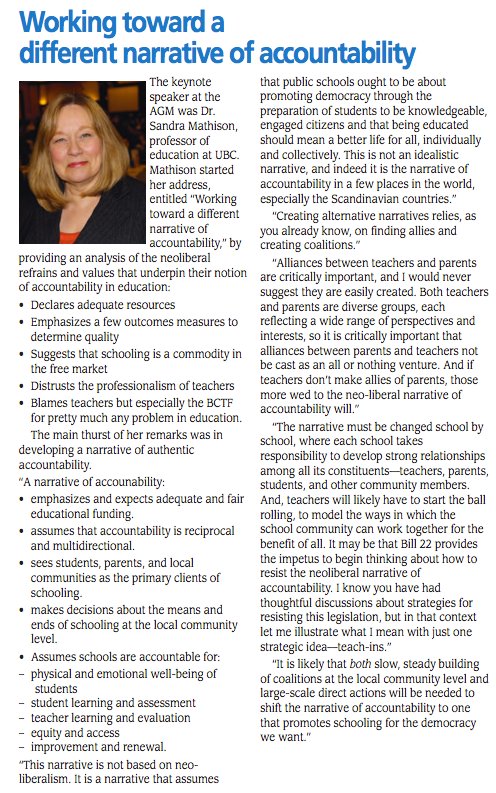

Whether it’s straight As or straight Cs, UBC education professor Sandra Mathison says parents should ask plenty of questions about a student’s report card, and cautions against rewarding good grades.

How useful are report cards?

There are different perceptions about what types of report cards are useful. What educators see as being appropriate is often not a view shared by parents. This is a fundamental contradiction.

Parents see marks within a framework of competition. Knowing that your child is getting an A means they’re in the top group, and if they get a C, then your child is doing a lot worse than some classmates.

For educators, the evolution of report cards is about providing information that is substantive and communicates, more specifically, the knowledge and skills that students are acquiring and demonstrating. That requires more detail. For example, educators can break “reading skills” down into phonemic awareness, comprehension, vocabulary, and so on.

Having detailed information communicates more clearly what kids know, and the move in most report cards is towards that. But parents often push back and say, “That’s too much information. I just want to know if my kid is doing OK.”

Are letter grades helpful?

Most of the time letter grades represent big categories and are therefore devoid of much meaning. If a high-school student gets a B in chemistry, what does that mean? Chemistry is complex. It has many components. Does the student understand the concepts, but struggles with those ideas in an applied laboratory context? Does the student understand the ideas but has a difficult time with nomenclature?

How should parents react to a less than stellar report card?

It’s more appropriate to ask what sense parents should make of report cards in general. A parent whose child gets all As should be asking questions, just like a parent whose child gets all Cs or Ds or Fs. Simply accepting some general level of performance, whether it’s very good or not, suggests you don’t actually want to know anything detailed about what your child is learning.

All parents, regardless of the letter grade, should say, “Help me understand in more detail what my child knows and can do, and what my child doesn’t seem to know and is having trouble doing.”

Ask the teacher to be analytic about the child’s knowledge and performance, and to show the parent work the student has done that shows something they’re struggling with. Then the parent can see and ask, “What can you and I do in order to help this child?”

Is it helpful to reward good grades with money or gifts?

It’s highly problematic. From an educational research perspective, we foster kids learning things because they have intrinsic value, not because they have rewards attached.

Parents and teachers should foster children’s interest in learning for the sake of learning, not the pursuit of grades or external rewards. When you give cash or gifts to students, you’re saying to them that what matters most are the outcomes. And when you put the emphasis on simple outcomes, such as getting an A or a particular score on a standardized test, it becomes a defining feature of learning. The quality of student thinking and their interest in the content is diminished when they focus on getting grades for gifts.

This short piece generated more media attention than I anticipated, perhaps because many of those in the media are themselves parents facing their children’s report cards.

A follow-up to this short piece was my segment on Stephen Quinn’s CBC On the Coast. Listen here.

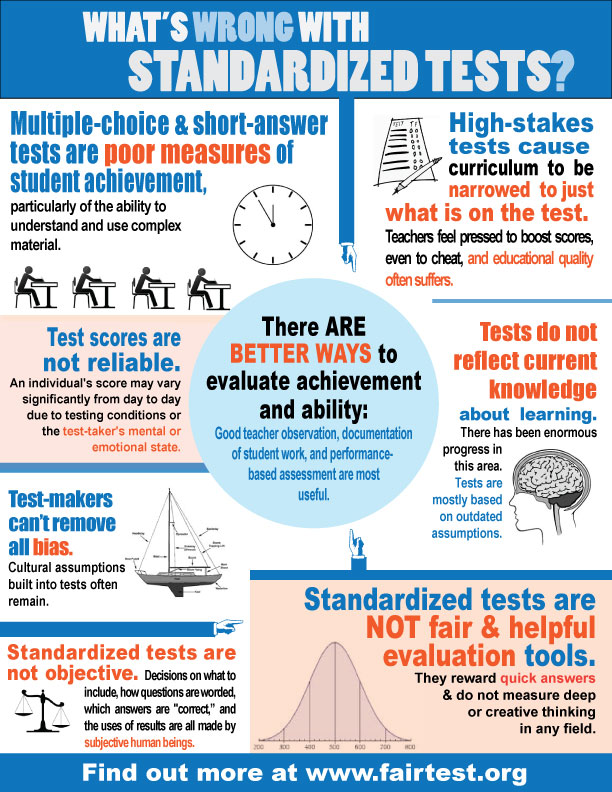

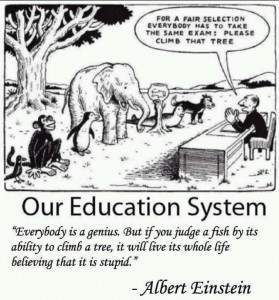

In educational evaluation the global educational reform movement (GERM) has privileged common indicators of student learning outcomes (used in turn for other evaluation purposes like teacher evaluation, even if not a sound practice). There are many reasons why standardized tests become the norm and are reified as the only fair and legitimate way to know how students and schools are doing. There is plenty of literature that debunks that idea.

In educational evaluation the global educational reform movement (GERM) has privileged common indicators of student learning outcomes (used in turn for other evaluation purposes like teacher evaluation, even if not a sound practice). There are many reasons why standardized tests become the norm and are reified as the only fair and legitimate way to know how students and schools are doing. There is plenty of literature that debunks that idea. Follow

Follow