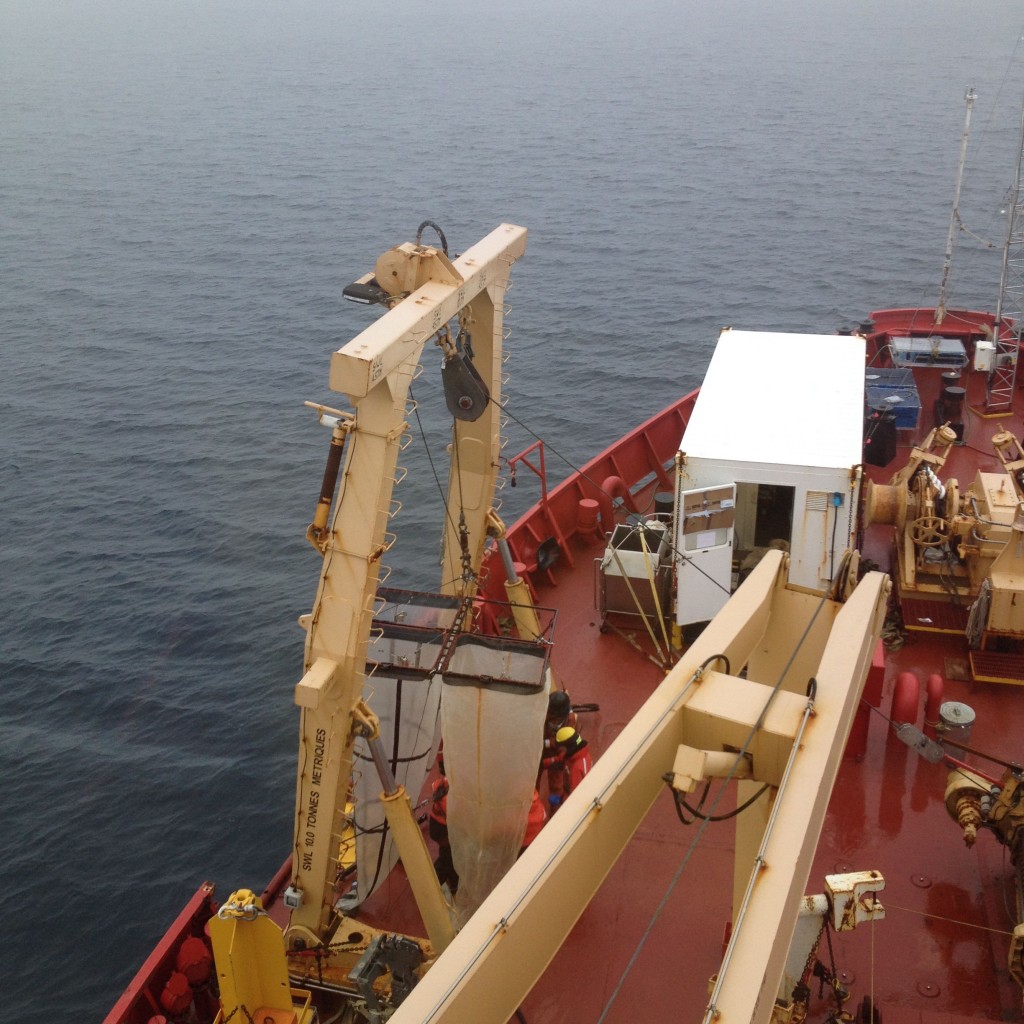

Any scientific work that happens on the Amundsen owes a great deal to the men and women of her crew, who work around the clock to keep us safe at sea in the northern ice. Today on the blog, I interviewed the person responsible for the operation of the ship’s engine room – Chief Engineer Abigail Lachance.

The Amundsen’s Chief Engineer, Abigail Lachance.

Ms. Lachance, thank you so much for taking the time out of your day to be interviewed. I’m sure readers of this blog are very interested to hear what a chief engineer does on the ship, and what you’re responsible for when you’re on the Amundsen.

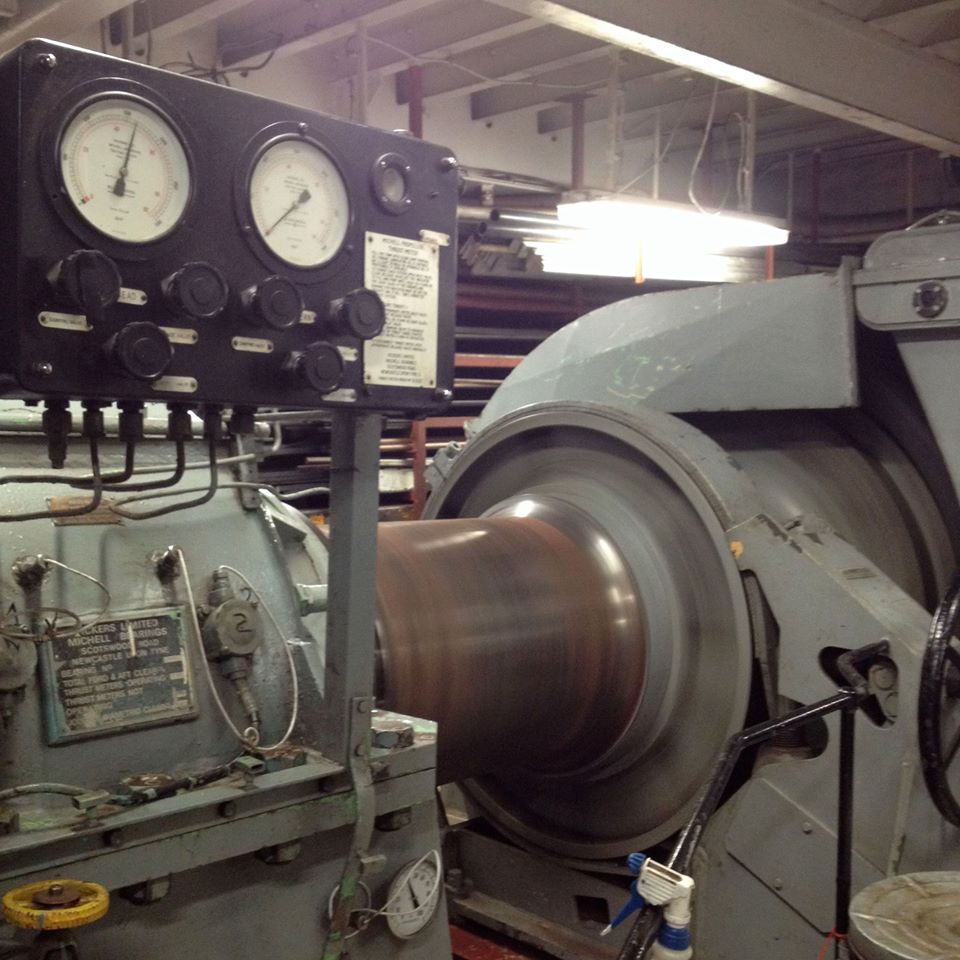

As Chief Engineer, I do a lot of paperwork stuff, but I’m responsible for the whole operation of the engine room. I delegate a lot of the hands-on stuff to the senior engineer and the rest of my team of three other engineers, an electrician, and six other assistant engineers, and they take care of all of the operations of the ship, the maintenance, anything that breaks down. The ship is pretty much a floating city, so everything that makes the ship run needs to be maintained, and the ship is quite old, so things break down on a regular basis. So if the lights are on, it’s because we’re doing our job right. If the toilets are flushing, it’s because we’re doing our job right, and if you have running water… All of the things that people take for granted, that’s the engine room department.

That sounds like a lot of things. So, for our readers, could you maybe describe a typical day. When do you get up, what do you do, when do you go to bed?

I can’t really say that there is such a thing as a typical day on the ship, because every day is different. As a Chief Engineer, I work a day shift. I work from 6:00 to 19:30, and anything that goes on in the engine room comes through me, but the engine room staff work different shifts. There is always somebody working in the engine room, and they work shift work. They work four hours of watches, and four hours of what we call conex, where they do the maintenance stuff that they can’t do when they’re on watch, they have a four hour rest, then they do another four hours of watch, and then they have eight hours off to have a good night’s sleep. So, as Chief, I have the nice daytime job, but if anything happens throughout the night, the engineers will call me – if it’s something they’re not sure about, they’ll ask my advice, or if they need my help…I’m on call all the time.

I think all of us scientists are kind of in awe of the ship’s crew, because you guys work so hard and you’re on all the time. When do you get time off? When do you leave the ship?

Well, in a typical summer trip, I leave the ship after six weeks.

For how long?

In general, the schedule is six weeks on, six weeks off, so we work six weeks, and it’s six weeks of twelve hours a day, hard work, and then we have six weeks off, when we can go home and just enjoy our time off.

What would you say is the most challenging part of your job?

The most challenging part of my job…I think, to be honest, it’s the personnel stuff. When we’re away for six weeks at a time, everybody goes through highs and lows, and everybody is living in close quarters, and things come up. People get frustrated and irritated, and people are getting tired. It’s when things like that start to deteriorate – I find that, as a Chief Engineer, a challenging part of my job. How to keep morale up, how to keep people motivated…the engineering stuff, I mean, we encounter problems all the time, and generally we have what it takes to figure out the problem. It’s more the morale stuff that’s the challenging part.

That makes a lot of sense. So, you’re currently in a very high position with the Canadian Coast Guard, and you have a fascinating job. What was the path that you took to get there? What schooling does that involve, where did you start out with the Coast Guard?

Personally, I went through the Canadian Coast Guard College. It’s a college that’s dedicated to training officers for the Canadian Coast Guard. The training we get applies to engineering in general, but there are some specific things that are really dedicated to the Coast Guard in particular. It was a four year program, and I graduated with a degree, and I started out as a junior engineering officer, working alongside other engineers, sort of learning the ropes, and then eventually started working as a third engineer and had my own watch, so I was responsible for specific equipment. The way engineering works, you accumulate sea time, you need to have a certain number of days at sea, and once you have those days at sea, you write another exam and get a third class ticket. When you get your third class ticket you can take higher jobs. And then, after a certain amount of time and experience, you get a second class ticket. With a second class, you can be Senior Engineer, which is just the next step, just below being Chief Engineer. And then, after another series of weeks and months at sea, I accumulated enough time to write my exams to get my first class ticket. With a first class ticket, I’m qualified to be Chief Engineer on any size of ship anywhere in the world. I’m a new Chief, I just got my ticket last year, and I’m the first woman Chief Engineer in the Québec region in the Coast Guard.

Congratulations.

How many years is that? How many years have you been at sea?

I’ve been at sea…I graduated from the College in 1995, so it’s been 20 years that I’ve been sailing. It is possible to go through the exams faster, but there is experience to be gained by sailing at different levels. I wasn’t in a rush to be Chief, so it took me a little while.

So, you mention that you are the first female Chief Engineer in the Québec region, from which I gather that it’s not a super common profession, still, for women today. What is it like for you being a female engineer? Is that an experience you can speak to?

Today, it’s much easier than it was 20 years ago. When I started out as a junior engineer, I was one of three women in the Québec region. I had a lot of guys taking tools from my hands, saying “no, I’ll do that for you”, and treating me like I didn’t know what I was doing. Over the years, the people that I work with have seen me, and see that I know what I’m doing. It took longer for me to get the acceptance of the people around me than it did for someone who graduated the same year as I did. We weren’t seen as having the same abilities. But, over the years, people have gotten to know me, and now it’s 20 years later, and most of the people who I come into contact with know me from my reputation. There are still some people that don’t like to have a woman as their boss in the engine room, and they don’t consider me to be qualified, but it’s 20 years later and attitudes are changing. There are still not many women in the engine room, but I think it’s just a lack of knowledge. A lot of girls just don’t know that this is a possibility.

On that note, when you say that a lot of girls don’t know that this is a possibility, what would you suggest to young girls, or young people, who are interested in this as a possibility? What would you recommend to them, from your position as someone with an extreme amount of experience?

Well, the Coast Guard College is hard to beat. If being an engineering officer is something that interests you, working with your hands, working on a ship, going on a ship, going on the adventures that we go on, doing the engineering, working on all different kinds of equipment, from sixteen-cylinder diesel engines to small little water pumps, to anything engineering and mechanics rated – if that’s the kind of thing that interests you, then I would recommend the Coast Guard college 100%. It’s a four year program, it’s subsidized by the federal government, so everything is paid for. You go to school, you get a salary while you’re there – it’s a small salary, but it’s a salary. All your books are paid for, your tuition is paid for, you’re supplied a uniform, you’re supplied pencils and paper, you’re supplied anything you could possibly need to go to school, and you graduate after four years with a degree and a diploma – the college is affiliated with the University College of Cape Breton – and a fourth class engineering ticket, which is recognized all over the world. You graduate and you start working as an officer right away. If you’re smart, you graduate with no debt. You can get the same program at the marine institute in St. John’s, there’s another one in Ontario, and another one in B.C – similar programs, where you study four years of engineering, but you don’t have the advantage of being targeted for the coast guard, and it’s a university where you have to pay your way through. In my opinion, if you’re looking at that type of career, why wouldn’t you go for free education, versus the one you have to pay for.

Thank you very much for the interview. Finally, I’ll end with a question I’ve been asking everyone that I’ve been interviewing on board the Amundsen. Can you share an interesting or a strange fact about yourself?

Oh my goodness. An interesting fact? I graduated in ’95, I wanted to go sail in Newfoundland, but I got posted in Québec, and I thought, oh, I’ll just come to Québec, and I’ll get a transfer in the next few months. And it’s twenty years later, and I’m still here.