This blog describes how we can use stick figure narratives in our educational development (ED) work.

This blog describes how we can use stick figure narratives in our educational development (ED) work.

My thoughts on this were inspired by a workshop facilitated by Dr. Jessica Motherwell McFarlane who presented at Symposium 2018. Dr. Motherwell McFarlane uses stick-figure narratives in her role as an instructor and counsellor to explore resiliency.

One of the premises of her work is that everyone can draw stick figures; consequently, it is not something that needs to be taught. Brain researchers, she explained, show that we instantly know when we are seeing stick figures and it is as if “a stick figure visual language app” comes with our brain. “Why not use it?!” she asked us playfully.

Dr. Jessica Motherwell McFarlane led us through several experiential exercises at the Symposium. In this post, I’ll describe these and consider how I could use these in ED.

Materials Needed

Each attendee received:

- 3 coloured markers, including one gel pen for writing on black paper

- Coloured donut-shaped reinforcement stickers (the kind used for loose leaf paper holes). Also called “loopy” stickers in the workshop. (10 or more)

- 5×8 blank index card (1)

- 5×8 black card stock (1)

Activity 1: “Something unexpected happened…”

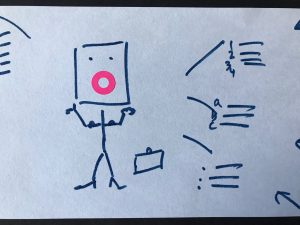

Within a few minutes of sitting down, we were asked to “show an image” or “make an image” depicting something funny and unexpected that had happened in our teaching. We were given a short time (I think it was 2 minutes) and one rule: We had to use at least one loopy sticker in our image–and we could use as many loopy stickers as we wished. We then got into trios and shared our stories and drawings.

I do not remember what I drew; nor what my story was. What I recall is feeling stressed at having to draw right away, having to come up with something “funny”, and the requirement to do so within such a short time limit. I had gone to the workshop because I anticipated it would make me feel uncomfortable–right I was!

When debriefing this activity, Dr. Motherwell McFarlane emphasized the importance of getting participants to draw almost immediately and of giving people only a short time to do so. She also intentionally avoids using the words “draw an image” because the word “draw” can generate a feeling of anxiety in people.

Application to educational development: The activity could easily become “tell the story of something funny or happy or unexpected that happened in your ED work”. This, and the two activities below, could be part of a session promoting reflective practice in ED.

Activity 2: “Emotional X-Rays…”

This was my favourite!

The instructions went something like:

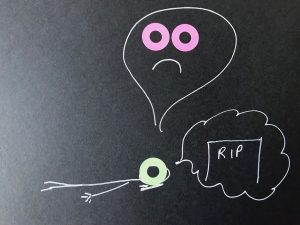

“You are going to create two images using stick figures and at least one loopy sticker. Use the white index card to show a situation in your educational development work (she used teaching), as it might be perceived by the people around you. Use the black card to show the same situation, as experienced internally by you.”

We had approximately 3 minutes to create both images and then shared the stories in trios or pairs.

Below are the two images I generated:

Image 1 (the “outside” view) Explained: My Fall has been very, very, very busy. I’ve had so many projects and have been applying my sharpest organizational skills and efficiency to complete these. The figure in this image is me flexing my ED muscles to keep various projects moving.

Image 2 (the “inside” experience) Explained: This fall has been one of the most difficult periods in my life as I have been providing intense support to my daughter in her recovery of anorexia (I am sharing this with her permission). I have been drained and sad much of the time.

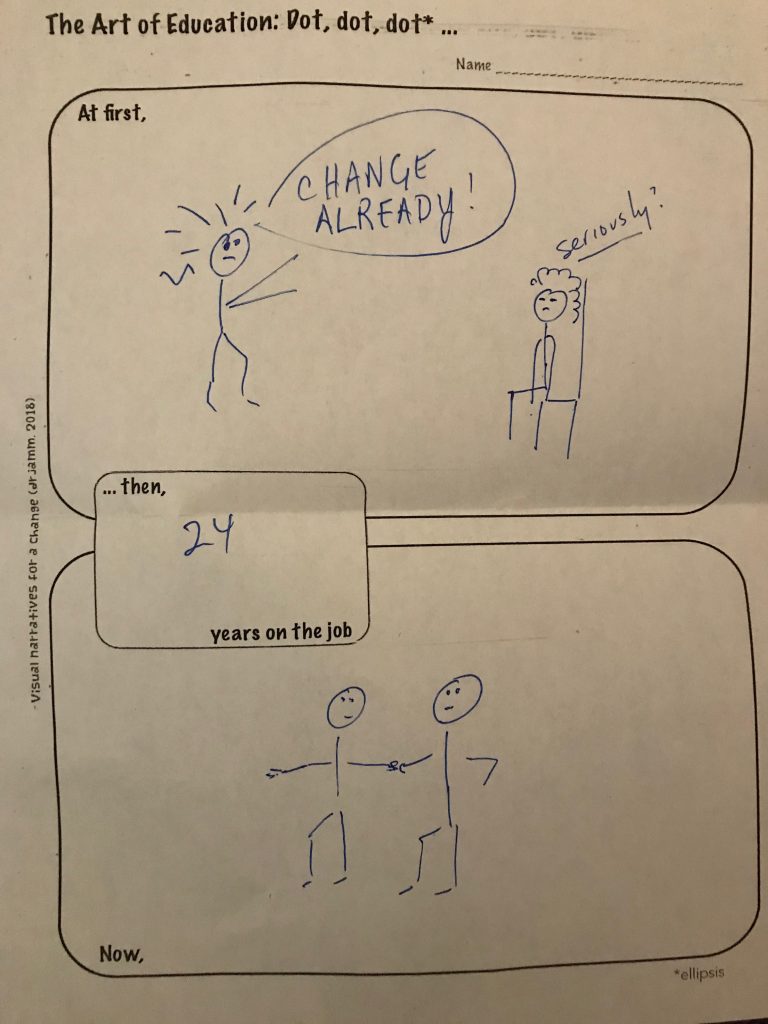

Activity 3: “Then and now…celebrating change”

This activity invites the image-maker to show and celebrate an aspect of one’s professional evolution.

The instructions went something like:

- Think about your role as a __________ (you could use ‘educational developer’; Dr. Motherwell McFarlane used ‘educator’; I considered my role as an adult educator). In the small, middle box, write the number of years that you have had that role (for me, 24 years as an adult educator).

- Think about a change in you over that period of time.

- In the top section, make an image that shows a way you used to do things/how things used to be…

- In the bottom section, make an image that shows what things are like now…

A few people were then invited to share* their Then and Now narratives using the document camera at the front of the room.

A few people were then invited to share* their Then and Now narratives using the document camera at the front of the room.

*Tip: Dr. Motherwell McFarlane has her own travelling (iPEVO HD USB) document camera and advised that it is helpful to assign one person to be collecting images and positioning them properly so that you, the facilitator, can focus on the storyteller and not on futzing with the image/direction/camera.

*****

This session was my favourite at the Symposium. If you decide to use stick figures or have thoughts on how you might use them, please send me an email or write a comment — I’d love to hear from you!

I’d like to give a BIG thanks to Dr. Motherwell McFarlane who so kindly read through a draft of this post, added details that I had accidentally omitted, and provided other helpful feedback.