I recently re-read the paper “Formative assessment and self‐regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice” by Nichol and MacFarlane-Dick (reference at end).

The paper looks at how to enhance feedback practices to support students’ self-regulation. Authors argue that formative assessment and feedback should be used to foster students to become self-regulated learners. This blog post contains some notes and excerpts from the pages 199-205.

Definitions

Formative assessment: assessment that is specifically intended to generate feedback on performance to improve and accelerate learning (Sadler, 1998 in Nichol & MacFarlane-Dick p.199).

Self-regulation refers to “the degree to which students can regulate aspects of their thinking, motivation and behaviour during learning” (Pintrich & Zusho, 2002 cited in Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006, p.199). (p.205 contains a good summary of research on SRL)

Self-regulated learning “is an active constructive process whereby learners set goals for their learning and monitor, regulate, and control their cognition, motivation, and behaviour, guided and constrained by their goals and the contextual features of the environment” (Pintrich and Zusho, 2002, p. 64 cited in Nichol & MacFarlane-Dick, p.202)

Student-centred learning: the core assumptions are active engagement in learning and learner responsibility for the management of learning (Lea et al., 2003 in Nichol & MacFarlane-Dick p.200).

The problem

In higher education, formative assessment and feedback are still largely controlled by and seen as the responsibility of instructors (instructors ‘transmit’ feedback messages to students about what is right and wrong in their academic work, about its strengths and weaknesses, and students use this information to make subsequent improvements) (p.200)

This is problematic because:

- impedes self-regulation

- assumes students understand the instructor’s feedback

- ignores how feedback interacts with motivations and beliefs

- increases instructor workload

Feedback and learning

There is considerable research that shows that effective feedback leads to learning gains.

Sadler (1989) identified three conditions needed for students to benefit from feedback in academic tasks. Students need to know:

1. What good performance is (i.e. the student needs to understand the goal or standard being aimed for);

2. How current performance relates to good performance (for this, the student must be able to compare current and good performance);

3. How to act to close the gap between current and good performance.

For students to do above, they have to possess their OWN evaluative abilities; they cannot solely rely on ‘outside’ source. Consequently, we need to help students with SELF-ASSESSMENT skills.

Feedback and learning: The model

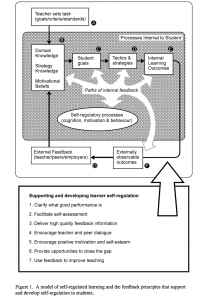

Nichol and MacFarlane-Dick present a model of self-regulated learning and the feedback principles that support and develop self-regulation in students. To see a larger version of this model, click on the above image. This image is from the author’s paper available here.

Good feedback practices: 7 principles

In this paper, good feedback practice is defined as anything that might strengthen the students’ capacity to self-regulate their own performance.

Good feedback practice (p.205):

1. helps clarify what good performance is (goals, criteria, expected standards);

2. facilitates the development of self-assessment (reflection) in learning;

3. delivers high quality information to students about their learning;

4. encourages teacher and peer dialogue around learning;

5. encourages positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem;

6. provides opportunities to close the gap between current and desired performance;

7. provides information to teachers that can be used to help shape teaching.

Reference: