Karen Jantzen

Introduction

Human rights violations and corruption by officials in many countries are pressing problems. A globalized world, where people and money cross borders, calls for global solutions to address those problems. Magnitsky legislation has been one attempt to do so through targeted sanctions. Magnitsky laws generally place immigration restrictions on designated individuals and freeze any assets they have in the imposer’s jurisdiction. The US was the first jurisdiction to enact Magnitsky sanctions. Canada largely copied that legislation with the enactment of the Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act (JVCFOA).

Reasons for lack of use of the JVCFOA

Canada has implemented three rounds of Magnitsky sanctions pursuant to the JVCFOA, but could greatly improve the program to make it more effective. Canada approaches the use of the JVCFOA with great caution, viewing it as a last resort in the foreign policy toolbox to be employed only when other diplomatic options are exhausted and when it is quite certain that its use will result in changing behaviour. There are also resource constraints to implementing the sanctions regime.

One constraint on the use of sanctions generally is the way in which they may be perceived by other states. Because sanctions are inherently political, there is always a risk that the imposing state might be accused of abuse, which can damage that state’s credibility. Inconsistency between the standards a country says apply to the actions of foreign states and the guiding principles of its actual policy, can further contribute to the belief that the decision to impose sanctions is driven by factors other than a concern for human rights abuses, depriving the sanctions of normative impact. Canada has also had questionable involvement in many situations of corruption and human rights abuse around the world, which could seriously limit its moral authority to deploy sanctions.

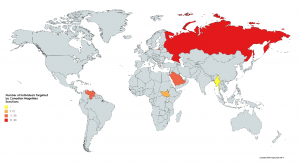

Targeted sanctions against individuals from a wide variety of countries can help the sanctions to be perceived more as legitimate global response and less as a personal attack on the target. Canada has only imposed sanctions on officials in five different countries, despite calls for wider use. As a point of comparison, the US has sanctioned individuals from 25 countries.

Working multilaterally

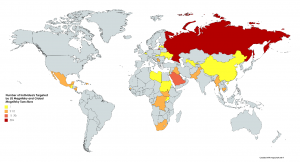

Because targeted sanctions are designed to affect the ability of individuals to move money obtained through corruption or used to support human rights violations across borders, the effectiveness of Magnitsky statutes can be maximized where there are not large geographical gaps in countries that have enacted them. Currently, only five countries have Magnitsky legislation, and many of the assets of corrupt officials worldwide are not located in those countries. Many countries have contemplated Magnitsky laws and the United Kingdom and the European Union appear to be moving forward with implementation.

Canada prefers to work collaboratively with other countries when deploying sanctions. It also relies on information sharing with partners regarding names and evidence. Hopefully, more countries acting together can produce pressure on each other to consistently deploy sanctions under their regimes, in addition to heightening effectiveness.

Currently, the existing and proposed Magnitsky legislation around the world is not harmonized. For example, the US legislation allows for entities as well as individuals to be sanctioned, and indeed has done so for 103 entities, while the JVCFOA can only designate individuals. It could be helpful to have a set of internationally agreed-upon rules, to ensure a shared understanding of definitions, how far states may go, and what international law requires.

The importance of transparency

Global Affairs Canada determines when to enact sanctions, writes regulations and legal opinions, and publishes the designations list. There is a lack of transparency surrounding all aspects of the process of sanctioning individuals. Concerns over due process arise from lack of clarity about the evidence at the basis of listing, as it can be difficult to determine if the requisite ‘reason to believe’ standard has been met.

The US Magnitsky legislation has a uniquely open consultation process whereby the president can consider for listings reliable information from human rights monitoring NGOs, which has the potential to bring some independence to implementation of the regime. Several civil society organizations in the US have produced guidelines to assist civil society in making sanctions submissions. Canada’s process is unclear. This raises questions about how effectively the legislation is being used.

I tried to get more information and clarity on the process of using the JVCFOA from Global Affairs Canada in the form of an Access to Information request. My request was received on October 15, 2019, but after exchanging emails with a representative, the wording of my request had to be amended because “[it] may yield a very high volume of records, which will take a significant amount of time to collect and process [and] most of [the documents] will be redacted.” On December 2, I received a letter that a 120-day extension was required to complete the processing of my request. I hope to receive at least some information by the end of March.

Conclusion

With the JVCFOA, Canada has the potential to play a significant role in sanctioning foreign officials who engage in corruption or human rights abuses. However, a greater willingness to deploy sanctions, more partnership with other countries, and increased transparency around the sanctions process are needed before this role can be realized.

Karen is a second-year student at the Peter A. Allard School of Law. As a clinician with the International Justice and Human Rights Clinic, she is working on a project related to Magnitsky sanctions.