By Daniel Szeto

As exposed by the “Panama Papers” data leak in 2016, international criminals have long exploited the gaps in Canada’s corporate beneficial ownership regulatory scheme to engage in corrupt conduct. It has been over a year since Canada initiated a public consultation, seeking feedback on the effectiveness of its current regime and the possible benefits from implementing a publicly accessible beneficial ownership registry. The findings from the consultation were recently published. On April 19, 2021, as part of the 2021 Federal Budget, Canada finally announced a commitment to invest $2.1 million over two years to create a public corporate beneficial ownership registry by 2025. Following a prior call to action, civil society groups welcomed the news of the Canadian government’s intention to increase the transparency of corporations with respect to their beneficial owners.

Image: Chrystia Freeland, Canada’s Minister of Finance, delivers the 2021 Federal Budget on April 19, 2021 [Source: The Canadian Press / Sean Kilpatrick]

Background

The lack of corporate ownership transparency in Canada enables perpetrators of serious financial crimes to set up shell companies and use them to funnel funds obtained through corruption or other illegal or criminal conduct. The complex corporate structures of these companies often rely on legal loopholes to avoid directly associating a company with the person who controls it (the “beneficial owner”), thus obscuring the identity of the persons ultimately receiving the profits of crime. James Cohen, the Executive Director of Transparency International Canada, notes: “Canada’s weak corporate transparency laws enable drug trafficking, terrorist financing, and all sorts of illicit activity abroad, but they also contribute to major social and economic problems in our own communities, such as the opioid and housing crises and proliferation of counterfeit goods.”

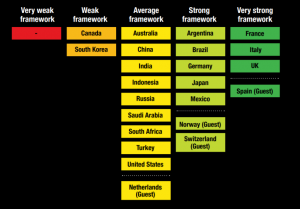

In 2014, Canada committed to strengthening corporate transparency by adopting the “High-Level Principles on Beneficial Ownership Transparency” at the G20 Brisbane Summit. Yet its progress has been slow relative to the other member nations. Three years after the initial pledge, Transparency International assessed Canada as one of two G20 countries that still had a “weak” beneficial ownership transparency framework.

Image: 2017 results for G20 beneficial ownership transparency framework assessment conducted by Transparency International [Source: Transparency International]

Federal Legislative Amendments

As a result of its Brisbane Summit commitment, Canada eventually amended its Canada Business Corporations Act (CBCA) in 2018, only to adopt the minimum guidelines set out by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).[1] The CBCA amendments require private companies incorporated federally to collect and maintain information concerning beneficial owners, denoted as “individuals with significant control” (“ISC” or “ISCs”) in the statute. Generally, ISCs would include “anyone with direct or indirect ownership or control over a significant number of shares of a corporation (i.e., 25 [percent] of the voting rights or fair market value of the outstanding shares), or who has any direct or indirect influence that, if exercised, would result in control in fact of the corporation, among other circumstances.” Up until now, Canada has opted for an internal registry regime, meaning the information is stored internally at a company’s registered office. Reported ISCs are not actively verified and their names and personal details are only available to certain investigative authorities upon specific request. There have been concerns that this system hinders access to timely information and prevents the implementation of effective investigations. As a result, criminals are not detected nor deterred and have continued to hide their illegal conduct by using Canadian companies to engage in money laundering and tax evasion schemes.

Global Developments

In contrast, a number of countries around the world have already made significant progress towards achieving corporate transparency. The United Kingdom has emerged as one of the leaders in beneficial ownership transparency after creating a public register of beneficial owners in 2016. The “people with significant control” (“PSC”) register is fully accessible and searchable online. Because it is “open access”, the register can be utilized freely by various stakeholders, including law enforcement, financial institutions, and civil society. Likewise, the European Union (EU) issued its Fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive containing a requirement for member states to introduce centralized beneficial ownership registers by June 2017. A subsequent announcement in the Fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive compelled EU countries to publicize these registers by January 2020. Most recently, the United States enacted the Corporate Transparency Act in January 2021, imposing reporting requirements to disclose certain personal details of beneficial owners of U.S. corporations, limited liability corporations, and other similar entities. Although the reports are not made publicly available, the data is stored centrally with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and may be released for law enforcement, national security, intelligence, or financial institution due diligence purposes. These new reporting requirements will come into effect by January 1, 2022, which is also the deadline for establishing accompanying regulations.

Pressure on Canada

Following the 2021 Federal Budget update, Canada now joins British Columbia and Quebec in taking concrete steps to mandating public disclosure of beneficial owners. Although the details of the registry are yet to be determined, it appears the recent global developments and the growing concerns from civil society were ultimately successful in pressuring Canada to initiate necessary action. It remains to be seen whether the other provinces and territories will follow the federal government’s lead and make similar commitments to prevent criminals from abusing their financial systems and corporate regulation regimes.

[1] Initially created by G7 nations, the FATF is an intergovernmental organization tasked with setting international standards to address issues of money laundering and terrorist financing.

Daniel Szeto is a 2L student at the Peter A. Allard School of Law and is working with the IJHR Clinic as part of the Magnitsky Team.