Jina Jeong

Climate change is a fast-moving and foreseeable catastrophe in the making. To avoid imminent climate catastrophe, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (“IPCC”), in a 2018 report, stressed the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions and contain the overall temperature increase from the pre-industrial era to 1.5 degrees Celsius. However, per the same report, governments are not doing enough.

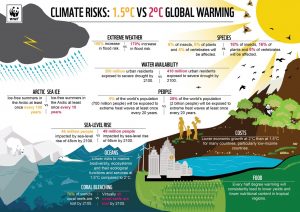

Climate risks at 1.5°C vs. 2°C warming. Infographic by World Wildlife Fund

Even if all Nationally Determined Contributions (“NDCs”) to reduce GHG emissions were met, as pledged by parties to the Paris Agreement, the IPCC predicts this would be insufficient to keep temperature increase below 1.5°C. On top of this insufficiency, many of the parties to the Paris Agreement are expected to fail to meet these modest goals. Unfortunately, there are no penalties imposed by the Agreement if states fail to meet NDC’s.

In response to lagging government action and lack of international accountability, concerned citizens, particularly the youth, are bringing lawsuits to domestic courts to hold governments accountable for insufficient climate policies. While domestic climate change litigation is a rising trend, success remains elusive, as recent cases show.

Climate demonstration in San Francisco, Photo by Li-An Lim on Unsplash.

Laudable decisions have been reached in high-profile cases such as Urgenda in the Netherlands and Future Generations in Colombia, where the highest courts of each country have held their respective governments accountable for their contributions to climate change. In each case, the courts ruled the governments had to perform mitigatory actions, such as a flat mandatory reduction of GHG emissions by 2020 in Urgenda.

However, in other cases, procedural hurdles have led to significant obstacles. In the high-profile US case Juliana, for example, the Court found that the legislative and executive branches, rather than the judicial branch, were the appropriate bodies to devise climate change remedies. This decision arrived only after a lengthy delay in proceedings due to the government repeatedly asking for stays or writs of mandamus, court orders that compel government agencies or lower courts to execute their duties. Closer to home in Quebec, the ENJEU case was similarly dismissed on procedural grounds for failing to meet the particular criteria of a plaintiff “class proceeding”.

Even where a case overcomes these procedural hurdles, and plaintiffs manage to secure a judgment against the government, there may be further obstacles in enforcing judgments due to the government’s unwillingness to comply. This is precisely the problem faced by the plaintiffs in the Future Generations case in Colombia; the plaintiffs will thus have to return to the courts to attempt to enforce the order against the government, lengthening the litigation process further. Therefore, even after a successful judgment, enforcement in some countries is not assured.

Considering the spectrum of both problems and solutions posed by the above cases, it remains unclear whether the large docket of pending climate lawsuits will result in holding the defendant governments responsible. At any rate, one thing remains clear given the worldwide nature of the climate change problem: one domestic judgment holding a single state actor responsible is insufficient to combat climate change by itself. What is required, at a minimum, is successful and speedy judgments in nearly all domestic courts of GHG emitter countries, particularly from the developed nations given their greater responsibility in current GHG emissions. However, given the above problems, it is possible that domestic judgments will achieve too little, too late to combat the climate change catastrophe that has arrived.

Given the global scope of climate change and the urgency of the matter, it seems logical that international fora may be better venues to pursue accountability for insufficient government action. As with domestic courts, however, procedural hurdles and potential unwillingness to adjudicate on the issue make the future of international climate litigation uncertain. Recent years have seen some climate change-related decisions from international fora such as the United Nations (“UN”) treaty bodies, the European Court of Human Rights, and to a limited extent, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Yet still, other major international bodies with arguably greater sway, such as the International Court of Justice (“ICJ”) or the International Criminal Court (“ICC”), have remained silent on the matter thus far.

Further problems lie in the fact that international bodies are not fully empowered to enforce their decisions against governments. For example, the UN treaty bodies’ decisions are not legally binding and are issued in the form of “recommendations”. Jurisdiction is also limited to the states that have ratified the relevant convention, treaty, or statute. The ICC, for example, cannot issue any binding decisions against the United States as it has not ratified the Rome Statute, the instrument empowering the ICC. International procedural rules in certain fora block climate change cases brought by individuals and groups. The ICJ, for example, can only hear cases brought by states against other states, so is not an option for affected individuals or groups.

Thus, for international fora to be effective at deciding climate change disputes, significant changes will have to be made to their mandates. While establishing an international forum dedicated to environmental issues may be the way forward, this possibility poses challenges of its own.

While the future of climate litigation appears murky, it is unquestionable that citizens around the world are increasingly mobilizing and calling for government accountability in relation to climate change. In light of the increasing support for the climate movement and the ever-greater acceptance of the science on climate catastrophe, one can hope that in the near future it will be possible to effectively pursue accountability for climate change from state governments.

Jina Jeong is a second-year student at the International Justice and Human Rights Clinic, Peter A. Allard School of Law. As part of her work with the Environmental Law Group, she provides research and assistance on cases seeking government accountability for climate change.