(Image uploaded from Flicker under creative commons license originally posted by Austin Kleon)

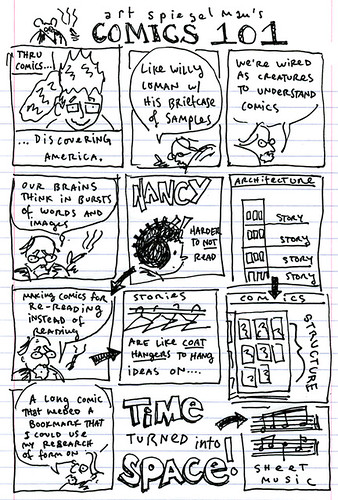

Writing prompt: “How is meaning made at the intersection of word and still image?”

Following Messaris, visual language (i.e., the still images in graphic novels) “obeys semantic conventions, but those conventions are rarely, if ever, entirely arbitrary, and the syntactic rules of visual language (i.e., the conventions of editing or montage) are so fluid and open to change that at times it can appear as if there are in fact no such rules at all.”

Since the semantic conventions of images are not entirely arbitrary but more a result of cultural (“multiple”) literacies – as opposed to the specialized discourse of highbrow literature and literary criticism – the ESL students that Frey and Fischer studied were able to construct meaning in ways that written text often does not allow. Graphic novels/manga/anime are said by Frey & Fischer to have “provided a visual vocabulary of sorts for scaffolding writing techniques, particularly dialogue, tone, and mood.” Judging by the results, the authors differing pedagogical approaches were largely successful in expanding on what the kids already knew.

In regards to Art Spiegelman’s Maus in particular, his use of masks (here is link to a piece on the subject with a .gif image from the novel to illustrate: http://wellread1.blogspot.ca/2008/10/maus.html) by some of the characters is brilliant, presenting just such an opportunity to scaffold, in this case to engage the students in an inquiry around the word/idea “persona”.

Simon Schama, in a review of Spiegelman’s Metamaus (a follow-up to the novel – here is a link to the publisher’s book trailer http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ql4oZtLruFE) opines that “Maus succeeded where so many more grandiose attempts to convey the enormity of genocide have failed, partly by side-stepping the adequacies, or inadequacies, of mere words to represent literally unutterable horror.”

I tutor kids in essay writing – many for whom English is also a second language – and have been quite resistant to including graphic novels in my practice, mainly because I thought they made textual interpretation easier for precisely the reasons mentioned above. My thinking was that, since students would be tested in the provincial exams and on the SAT on their abilities to analyze and produce without visual aids/prompts, it would be useless to allow them a crutch. After reading Maus and reflecting on what others like Schama (a very well respected art critic/theorist) have said, I’ve come to see the genre differently: just because graphic novels like Maus re-imagine biography and history (or whatever “classic” genre) as fable does not invalidate the genre. In other words, if you want kids to succeed in the future they will create, give them tools they need by any and all means, not just using the ones you learned/value. Part of this is facing the fear that you do not have total command of these emerging literacies either, as (thankfully) we have often admitted in class (I have challenged myself to learn how to use Prezi to fashion my next weblog entry.).

Another reason why I’m beginning to think differently about graphic novels has to do with the inevitability of the cultural shift. The momentum is inexorable, and eventually the school curriculums will be forced to change as a result. A quote from one of the articles I read to write this weblog (entitled “On the Origin of Adaptations: Rethinking Fidelity Discourse and ‘Success’ – Biologically’.) sums up my thinking on this (as per Messaris, ‘analogically’ speaking…): “As in biological evolution, descent with modification is essential.”

Finally, I want to share the postscript to the “Using Graphic Novels…” article entitled “EJ 75 Years Ago”. The postscript is a quote from a contributor to EJ by the name of Wanda Orton (from 1929!): “Do you try to break the age in which you live or do you try to understand it?” Clearly, we have a responsibility as educators to not only understand, but actually master the age; but in the end, can we really expect to stay ahead of the kids we are trying to teach? Perhaps the best we can expect of ourselves is to “denaturalize” the semantic/syntactic connections our students unconsciously make when presented with visual imagery (to paraphrase Messaris)?

Works Cited

Bortolotti, Gary R. Hutcheon, Linda (2007). “On the Origin of Adaptations: Rethinking Fidelity Discourse and ‘Success’ – Biologically’. New Literary History, Volume 38, Number 3, pp. 443-458

Frey, N. and Fisher, D. (2004). “Using Graphic Novels, Anime, and the Internet in an Urban High School.” The English Journal, 93(3), pp. 19-25.

Messaris,P. (1994). Visual literacy: Image, mind, reality. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Orton, Wanda (1929). “Released Writing.” The English Journal, 18(6), pp. 465-73.

Schama, S. (2011). MetaMaus. FT.Com, , n/a. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/905055822?accountid=14656

2 responses so far ↓

dinouye // Sep 22nd 2012 at 3:52 pm

Excellent. I agree that we need to be open to understanding, blending and incorporating change, and that this is often times a challenging feat. Here’s to learning with and from our students! Thanks for the wonderful links also.

TMD // Sep 26th 2012 at 9:02 am

Thanks for this interesting post. I agree: our mandate as ELA teachers is not to protect some ideal of our discipline, it is to prepare students to be able to communicate and understand knowledge sources within our contemporary context. We also have a mandate to follow the curriculum that governs our discipline — and that curriculum in the BC context moves well beyond text.

If individuals in this class haven’t already done so, do take a look at the BC Ministry of Education Provincial Exams for ELA. Several are posted online (do a Google search to find them). You’ll find analysis of visual texts is part of several exams.

Teresa

You must log in to post a comment.