Disclosure: I am a RENT-head. And I love to cry.

Disclosure: I am a RENT-head. And I love to cry.

On a bright and very early morning in the spring of 1997, I stood with a friend, in a long and winding line, outside the Nederlander Theatre on Broadway and 41st. We were waiting to get student rush tickets to the preview production of RENT. We felt as if we were taking part in something larger than ourselves; we were a part of a community, a culture. We got front row seats. And my life was subsequently transformed.

This rock musical had a profound effect on me. I felt as if it related to me. I was a student, I was a bohemian, I was urban, I was young, I was drawn to “counter-culture” and social justice, I knew people who were living with and dying of AIDS, and I was a romantic who yearned to be in love.

It didn’t matter (did it?) that I was unaware that this musical was an adaptation of Puccini’s opera La Boheme?

A few years later, I saw the opera La Boheme. The themes and characters of course were familiar: bohemian life, poverty, romantic interest, disease, death (near-death in RENT). The romanticization and the marginalization of bohemian life, the love triangles: these proverbial themes, bolstered by the connections I was able to make between the two musical forms, were a source of engagement. Even the similarities between the names (Roger-Roggiero, Mimi etc) were a source of interest and delight for me.

Seeing La Boheme, in the context of RENT, made me appreciate it and enjoy it on a deeper level.

The question then arises: How is viewing the “original” or predecessor affected/framed by the adaptation? Does it matter which is seen first and which second?

It seems to me, it doesn’t much matter what the “source” is, what is seen first or second. Each has life of its own that both reflects particular socio-cultural circumstances, and resonates with universal themes. This is the crux I think – the cultural relevance and milieu: the “narrative phenotype” in the words of Bortolotti and Hutcheon. In other words: the combination of the narrative story (thematic elements) plus the cultural relevance/milieu –“allowing the story to fit a particular culture or environment.”

The interesting thing here is how narratives change over time, and why and how certain ideas can be adapted to new audiences: why we choose to retell certain themes that can be traced back (“lineage of descent”) and how these choices function within culture. This to me rings of the enduring particular-universal paradox: the magic of locating universal threads within particular settings.

To me, success is premised on whether the story, in whichever form, made me cry! As long as the conditions for the cathartic “moments” are there, it has served its purpose.

High, low, original, and derivative are moot terms. An adaptation stands on its-own; it breathes its own life. Fidelity to the original is irrelevant to an evaluation of success. An adaptation is successful in “propagating the narrative for which it is a vehicle” (Bortolotti and Hutcheon). It is successful in that it makes us re-engage with this narrative, in novel ways.

Having said all this, I remember being very anxious and ambivalent about seeing the movie RENT when it came out. I didn’t want it to interfere with my “sacred” experience of RENT Live. The temporal and spatial and conceptual distance from Puccini to Jonathan Larson was a space I was comfortable with. But from RENT the Broadway musical to RENT the movie? Here were expectations of fidelity. Why? Does temporal and spatial proximity have to do with such expectations?

Perhaps it’s a generational thing: “These kids don’t even know the original!” But now I ask myself: Does it matter? Why? The important thing is that people find it meaningful in some way. And hopefully, it will prompt them to explore other forms, variations, and adaptations, and to proliferate this very conversation.

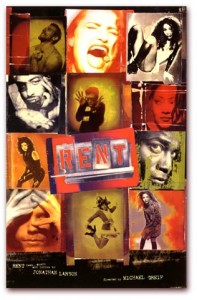

Post script: Following a reading of Messaris’s article on visual imagery, I am adapting the term paraproxemics in relation to the original RENT poster, arguing for the function of the closeness of the camera-subject relationship (the close-up faces) as affecting viewers’ emotions and attitudes as it reflects interpersonal distance as a regulator of intimacy. There is something about the “in-your-face-ness” of it that is bold, striking, youthful, and arguably, a little oppositionary, all of which go along with the energy and underlying message of the bohemian cast of characters.

Works cited:

Bortolotti, G. and Hutcheon, L. (2007). On the Origin of Adaptations: Rethinking Fidelity Discourse and “Success” — Biologically. New Literary History, 38(3), pp. 443-458.

Messaris, P. (1998). Visual Aspects of Media Literacy. Journal of Communication, 48(1), 70-80.

3 replies on “One Great Song (that doesn’t remind us of Musetta’s Waltz)”

I always forget to add my name to the post. Here it is. See if you can find me in the production shots!

Thanks for the interesting post, Dana. I agree with your perspectives and have written a comment related to this topic of how we experience adaptation in response to one of Kiran’s posts: https://blogs.ubc.ca/lled368/2012/10/07/i-am-he-as-you-are-he/#comments

La Boheme is next in line for Vancouver Opera, by the way: http://www.vancouveropera.ca/La-Boheme-2012-13.html

Yes. The idea of “reverse fidelity” is interesting. I was going to add also that while my viewing of Boheme was informed and enhanced by my viewing of RENT, subsequent viewing of RENT were informed and enhanced by my viewing of Boheme. So it’s this perpetual interplay of products and processes.