This is the fourth in a series of dispatches from our field work in the Republic of Marshall Islands.

This is the fourth in a series of dispatches from our field work in the Republic of Marshall Islands.

The geography of sports in the Pacific Islands is a bit of a lens into the colonial history and ongoing international power dynamics. There’s the rabid popularity of rugby in once-British Fiji. Then there’s the ‘export’ of football players from American Samoa, a U.S. territory where people are not granted U.S. citizenship and cannot vote for president.

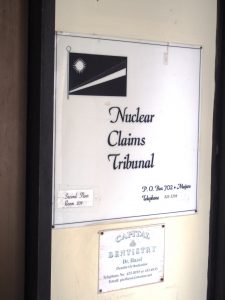

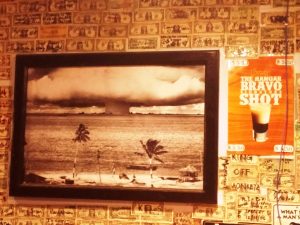

In the Marshall Islands, which has its own complicated relationship with the U.S., the sport of choice is basketball.

In the capital of Majuro, there are hoops attached to posts, palm trees, walls, you name it. There are quite a few well-maintained places to play, including the covered outdoor courts in front of the College of the Marshall Islands. However, many aging nets, hoops and backboards stay standing for years for the reasons described in my first dispatch: the challenge of getting new materials and disposing of waste on isolated reef islands.

Without further adieu, I present the hoops of Majuro: