Wentao Li | MEL Clean Energy Candidate | Dec 03, 2024.

Mentors: Varun Narayan, Wanying Shi and Heather Jones, S&P Global

ABSTRACT

Abstract

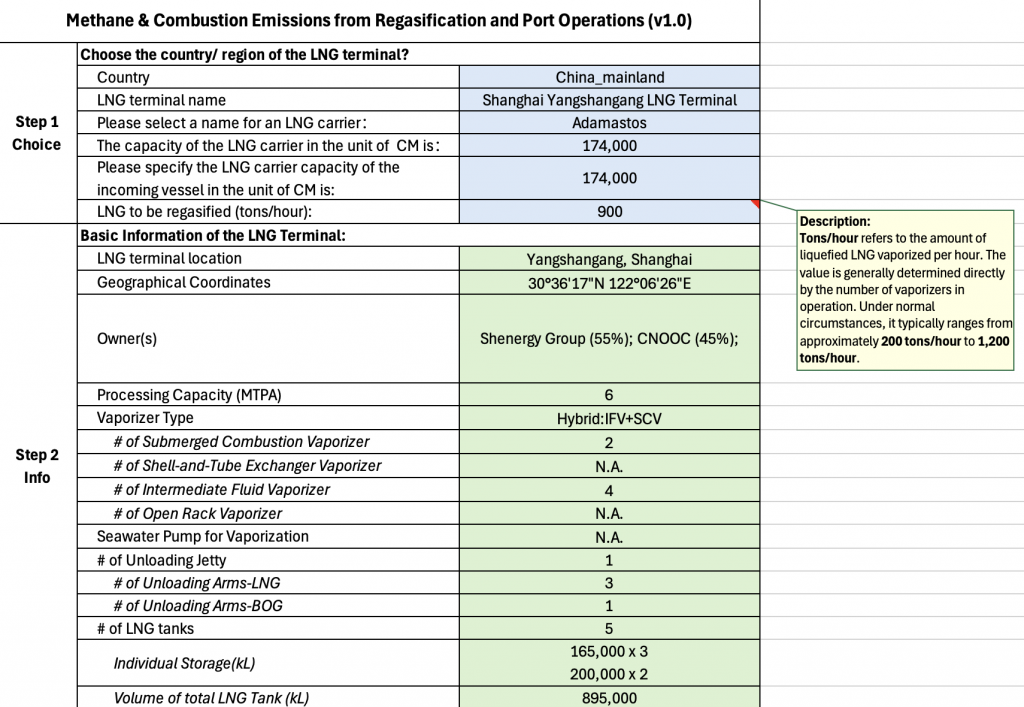

This project focuses on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions during the regasification process at LNG terminals, with detailed analysis of facilities in China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. The study examines key emission factors, including those from the unloading process, Submerged Combustion Vaporizers (SCVs), Open Rack Vaporizers (ORVs), Intermediate Fluid Vaporizers (IFVs), and the electricity consumption of seawater pumps. By leveraging terminal-specific data and integrating electricity emission factors, the research estimates CO₂ equivalent (CO₂eq) emissions for each stage of regasification. The model enables the selection of specific terminals, allowing users to calculate the total CO₂eq emissions for a single LNG cargo’s regasification process, providing actionable insights for emission reduction strategies.

INTRODUCTION

This LNG regasification model provides a comprehensive tool for estimating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, including CO₂ equivalent (CO₂eq) emissions, during the regasification process at LNG terminals. The model incorporates detailed terminal-specific data for countries like China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, offering insights into emissions associated with each stage of regasification.

Key Features

1. Detailed Data Integration:

- Includes terminal-specific parameters such as LNG vaporizer types (SCV, ORV, IFV), unloading arms, seawater pumps, and regasification capacities.

- Utilizes verified sources and assumptions to standardize emission factors for comparison.

2. Emission Sources Covered:

- Unloading Process: Estimates methane leakage and CO₂ emissions from LNG carrier unloading arms.

- Vaporizers: SCVs and STVs: Emissions from burning methane for regasification heat; ORVs and IFVs: Lower emissions by leveraging seawater or intermediate fluids as heat sources.

- Seawater Pumps: Power consumption and CO₂eq emissions from electricity used for pumping seawater.

3. Customizable Scenarios:

- Users can select a specific terminal and input the LNG cargo’s capacity to calculate total CO₂eq emissions for a single shipment.

- The model provides outputs for total emissions based on the terminal configuration, equipment efficiency, and operational factors.

METHODOLOGY

This LNG regasification model integrates detailed data to estimate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, focusing on methane emissions, combustion emissions, and electricity usage. Methane emissions during the unloading process are derived from studies like Balcombe et al. (2022) and Journal of Pipeline Science and Engineering (2024), estimating engine emissions at 0.000025 kg, venting at 0.00000012 kg, and fugitive emissions at 0.00000004 kg per ton of LNG unloaded. Leakage at flange connections is also included for accuracy.

Combustion emissions are modeled based on the vaporizer type. Submerged Combustion Vaporizers (SCVs) consume 1.5% of LNG mass for heat, with 0.14% of methane remaining unburned, as reported by Sea-Man.org. ORVs and IFVs, which use seawater or intermediate fluids as heat sources, emit approximately 28 times less CO₂eq than SCVs, making them more environmentally friendly.

Electricity consumption for seawater pumps is calculated as 3.5 kWh per ton of LNG processed, based on data from Sinopec Engineering Inc. For a 1,000-ton-per-hour terminal, the pumps consume 3,500 kWh, resulting in CO₂ emissions of 1,473.5 kg/hour using an emission factor of 0.421 kg/kWh (EPA GHG Emission Factors Hub).

Terminal-specific data, such as the Guangdong Dapeng LNG Terminal’s capacity of 6.8 MTPA and hybrid SCV-ORV vaporizer system, are used to customize calculations. The model also applies standardized assumptions, such as methane’s global warming potential (GWP) of 25 times that of CO₂, as per the IPCC GHG Protocol.

By selecting a terminal and inputting cargo capacity, the model calculates total CO₂eq emissions. For example, a 1,000-ton-per-hour terminal emits 15,000 kg of CO₂ from SCVs and 1,473.5 kg from seawater pumps, totaling 16,473.5 kg/hour. This methodology offers a precise framework for emissions analysis, enabling actionable insights for LNG terminal optimization.

RESULTS

The results of the analysis provide a detailed breakdown of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions during the LNG regasification process, highlighting the contributions of methane slip, CO₂ emissions, and the performance of different vaporizer technologies.

Methane Emissions

Methane emissions from Submerged Combustion Vaporizers (SCVs) are calculated at 1.5% of the LNG’s mass, reflecting methane slip due to incomplete combustion. Additionally, fugitive emissions from terminal equipment, including valves and connections, account for approximately 0.14% of methane losses. Although relatively minor in mass, the high global warming potential (GWP) of methane significantly amplifies its environmental impact.

CO₂ Emissions

CO₂ emissions are driven by the electricity required to operate seawater pumps and the combustion processes in SCVs. The model estimates that regasifying one ton of LNG requires 3.5 kWh of electricity, translating into 1.473 kg of CO₂ per ton of LNG processed, based on a CO₂ emission factor of 0.421 kg/kWh. These electricity-related emissions are particularly significant for high-capacity facilities, underscoring the importance of energy efficiency in terminal operations.

SCVs contribute substantially to CO₂ emissions due to their reliance on methane combustion for heat. The emissions from SCVs are approximately 28 times higher than those from Open Rack Vaporizers (ORVs) and Intermediate Fluid Vaporizers (IFVs), which utilize seawater or intermediate fluids as heat sources. These findings reveal the inefficiency and high carbon footprint of SCVs compared to alternative technologies.

Emissions Analysis

The study also highlights the emissions profile of the LNG unloading process. While CO₂ emissions from LNG carriers account for 62.3% of total CO₂eq emissions during unloading, methane leakage at unloading arm connections is negligible. This result reflects improvements in containment technology at terminals but indicates the need to address CO₂ emissions from carriers.

Overall, the analysis identifies SCVs as the dominant source of GHG emissions during regasification, followed by emissions from electricity use for seawater pumps. In contrast, ORVs and IFVs demonstrate significantly lower emissions, offering a viable pathway for reducing the carbon intensity of LNG terminals.

Summary of Results

- Methane slip from SCVs accounts for 1.5% of LNG mass, with 0.14% additional fugitive emissions.

- Electricity usage contributes 1.473 kg of CO₂ per ton of LNG processed.

- SCVs produce CO₂eq emissions approximately 28 times higher than ORVs/IFVs.

- During the unloading process of LNG, CO₂ emissions from the LNG carriers account for 62.3% of the total CO₂ equivalent emissions for the entire operation, while methane leakage at the unloading arms is negligible.

These findings provide a clear emissions profile for LNG regasification, offering actionable insights to improve energy efficiency, reduce reliance on SCVs, and transition to cleaner vaporizer technologies.

DISCUSSION

While the LNG regasification model provides a detailed framework for estimating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, several limitations should be acknowledged, reflecting data constraints and assumptions made during its development.

- Incomplete Data for Certain Terminals: Detailed information on LNG terminals in Japan and China is partially missing, particularly regarding the types and numbers of vaporizers used at these facilities. This gap limits the accuracy of emission estimates for these specific terminals and necessitates reliance on assumptions or generalizations.

- Substitution for Methane Leakage Rates: The model lacks precise data on methane leakage rates at the connection points between LNG unloading arms and LNG carriers. As a result, the leakage rates for terminal flange connections are used as a substitute, which may not accurately reflect the true methane emissions during the unloading process.

- Use of U.S. Electricity Data for GHG Calculations: Due to a lack of region-specific data for East Asia, the model adopts the CO₂ emission factor for electricity generation from U.S. data (0.421 kg/kWh). Since regional electricity grid compositions vary significantly, this assumption may lead to inaccuracies in estimating emissions from seawater pump operations in East Asian LNG terminals.

- Limited Seawater Pump Power Data: The operational power data for seawater pumps is derived from a single LNG terminal in China. Actual power consumption may vary across terminals depending on their design and operational characteristics, potentially affecting the accuracy of the emissions estimates.

- Fixed Unloading Rate for LNG Arms: The model assumes a fixed LNG unloading rate of 3,500 m³/hour for all terminals. However, unloading rates can vary depending on the terminal’s equipment and operational efficiency, introducing potential discrepancies in emissions calculations during the unloading process.

These limitations highlight areas where further research and data collection are necessary to enhance the accuracy and applicability of the model. Incorporating more detailed and region-specific data would enable more precise emissions estimates and strengthen the model’s value for decision-making and policy development.

CONCLUSION

This LNG regasification model provides a comprehensive framework for estimating greenhouse gas emissions across various stages of the regasification process, offering insights into methane slip, combustion emissions, and power-related CO₂ emissions. Despite its utility, the model’s accuracy is constrained by limitations such as incomplete terminal data, reliance on substitute parameters for methane leakage rates, and the use of U.S. electricity emission factors for East Asian terminals. Additionally, assumptions regarding seawater pump power consumption and LNG unloading rates may not fully capture terminal-specific variations. Addressing these gaps with region-specific and detailed operational data will enhance the model’s precision, making it a more reliable tool for emissions analysis and supporting efforts to optimize LNG terminal operations and reduce their environmental impact.

REFERENCES

Balcombe, P., Heggo, D. A., & Harrison, M. (2022). Total methane and CO₂ emissions from liquefied natural gas carrier ships: The first primary measurements. Environmental Science & Technology, 56(13), 9632-9640. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c01383

Global Energy Monitor. (n.d.). Pyeongtaek LNG Terminal. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://www.gem.wiki/Pyeongtaek_LNG_Terminal

GIIGNL. (2023). The LNG industry annual report 2023. Retrieved November 27, 2024.

Guest. (n.d.). LNG vaporizer selection based on site ambient conditions. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://pdfcoffee.com/qdownload/lng-vaporizer-selection-based-on-site-ambient-conditions-pdf-free.html

International Gas Union (IGU). (2024). 2024 World LNG Report. Retrieved November 27, 2024.

Jia, W., Jia, P., Gu, L., Ren, L., Zhang, Y., Chen, H., Wu, X., Feng, W., & Cai, J. (2024). Quantification of methane emissions from typical natural gas stations using on-site measurement technology. Journal of Pipeline Science and Engineering, 100229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpse.2024.100229

KOGAS. (n.d.). Pyeongtaek LNG Terminal. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://www.kogas.or.kr/site/eng/1030603010000

Lavoie, T. N., Shepson, P. B., Gore, C. A., Stirm, B. H., Kaeser, R., Wulle, B., Lyon, D., & Rudek, J. (2017). Assessing the methane emissions from natural gas-fired power plants and oil refineries. Environmental Science & Technology, 51(6), 3373-3381. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b05531

POSCO Energy. (n.d.). Gwangyang LNG Terminal. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://eng.poscoenergy.com/_service/business/generator/lngterm.asp

Sea-Man.org. (n.d.). LNG regasification: How it works. Retrieved November 21, 2024, from https://sea-man.org/lng-regasification.html

Sinopec Engineering Inc. (SEI). (2022). Sinopec Zhejiang Zhoushan Liuheng LNG project (Phase 1, Stage 1) receiving station feasibility study report – Volume 4 (Internal version). Sinopec Engineering Inc.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2024). GHG emission factors hub [Excel file]. Retrieved November 21, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-02/ghg-emission-factors-hub-2024.xlsx

WeChat Platform. (n.d.). The 28 Chinese LNG terminals summary. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/22lVmdcxsPex944fOgDE5A

CONTACT DETAILS

Wentao Li, BEng, Meng, MEL

Email: wentao.li.apply@gmail.com

Phone Number: +1(236) 965-9767