Children Who are Blind or Have Low Vision

Children who cannot see at all or who have some vision but not enough to make sense of the world are considered visually impaired (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Visually impaired

A visual impairment can be determined in two ways (for more information about the definition of visual impairments, please visit the birth to six part of this course:

- How well a child sees or visual acuity: perfect vision is 20/20. This means that a person can clearly see at a distance of 20 feet what they are supposed to see at 20 feet;

- How much peripheral vision a child has or visual field: when looking straight ahead, a child should be able to see part of his environment, to the left and the right;

When a child cannot see clearly, or does not have enough peripheral vision after correction (with glasses or contact lenses) or surgery, he or she is considered visually impaired. Vision loss can be congenital (present at birth) or adventitious (vision is lost later in life, due to illness, accident, injury or trauma). Although most children who are visually impaired do have some vision left, many cannot use their vision in order to make sense of the world. In other words, they do not have functional vision.

There are many types of vision loss, some of which are listed below1:

- Refractive errors, such as myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (far sightedness), and/or astigmatism;

- Cataract: resulting from clouding of the lens of the eye;

- Glaucoma: resulting from too much pressure in the eye;

- Retinitis pigmentosa: starts with night blindness and usually progresses to loss of peripheral vision.

Some vision impairments are degenerative. This means they get worse with age. Others are degenerative by nature and vision loss gets worse, even in children (for example: glaucoma). Also, some children have a visual impairment that is stable; that is, it does not change. Others have visual impairments that fluctuate. That is, the child can see better or worse on different days (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Blind

Vision loss or low vision can have serious effects on the development of the child:

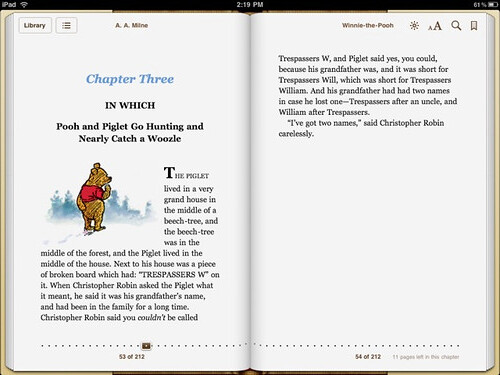

- Cognitive and academic skills: children who are blind or have low vision often reach developmental milestones later than their sighted peers. It is not easy (though certainly not impossible) to explore objects and play with them when you cannot see them. It is also not easy to move around and explore your environment if you cannot see it. Children who are blind or have low vision may also struggle with academic skills, such as reading, writing and math. Children who are blind usually learn how to read by using Braille (see full Glossary) (Fig. 3), and those who have low vision usually use large-print books, or special equipment that makes the font of books larger. Some children who are blind or have low vision struggle with the development and understanding of certain concepts and need to be taught certain skills over and over again;

Figure 3. Reading Braille

- Motor skills: most children who are blind or have low vision will reach motor milestones later than their sighted peers. For instance, it is very difficult to start reaching for objects (which starts at around 4 months of age in sighted children) when you cannot see them. It is also difficult to crawl and cruise (see full Glossary) (which can happen at around 10 to 12 months in sighted children), if you cannot see where you are going. Most children eventually do catch up with their sighted peers;

- Language and communication: many children who are blind or have low vision experience difficulties with language. Many have language skills that are less advanced than those of their sighted peers. They sometimes struggle with concept development and may have difficulty understanding abstract words (such as freedom or justice);

- Adaptive: some children who are blind or have low vision may struggle with adaptive development. They may struggle with tying their shoe laces, making sure they are wearing the same socks or shoes on both feet, and bathing and grooming. They can be taught how to manage these difficulties by a vision specialist;

- Social/emotional: some children who are blind struggle with both social and emotional issues:

- Social issues: because they cannot see or cannot see well, many children who are blind or have low vision engage in what is referred to as “blind mannerism.” This term refers to behaviors such as rocking back and forth. Some children who are blind or have low vision may engage in such behaviors because they are not getting enough stimulation through their various senses. Some children who are blind or have low vision may not know when to enter or leave a conversation because they cannot see the “social cues” that are being given to them by others. Speech and Language Pathologists (SLPs) can teach these children how to recognize these cues;

- Emotional issues: some children who are blind or have low vision struggle with having low self-esteem and little self-confidence. Most usually overcome these difficulties in their adult years, if not earlier;

Because of these difficulties, children who are blind or have low vision could benefit from the following services:

- Orientation and mobility specialist: this person will help the child who is blind or has low vision “orient” him or herself in physical space and then move from one place to the next (mobility) with little or no assistance. The orientation and mobility specialist will also teach the child who is blind or has low vision how to interact with his or her seeing eye dog, if he or she has one, and how to use his or her cane, if he or she has one;

- Speech and language pathologist: the SLP could help children who are blind or have low vision learn pragmatic language;

- Special educator with special training in visual impairments(sometimes called an itinerant teacher): this person will help the child who is blind or has low vision with any academic difficulties he or she may be experiencing. The special educator will also help these children with any adaptive equipment they may have (for example, a special device that turns regular words into Braille). The special educator will also help the regular education teacher accommodate the child who is blind or has low vision into his or her classroom, and change the physical setting of the classroom, in order to make it “blind friendly.” For example:

- The physical set up does not change unless the child who is blind or has low vision is informed first;

- The child is seated in the place that provides him or her with the most amount of light possible;

- The child is given enough space to keep his adaptive equipment with him or her.

Some children who are blind or have low vision start their academic lives by attending special schools for the blind. There, they learn how to read Braille, and use canes or seeing eye dogs. They also learn how to orient themselves in their environment in order to become as independent as possible.

Here is a list of what most children who are blind or have low vision need, in order to be as independent as possible:

- Books in Braille (see full Glossary) (Fig. 4): if they use Braille and books in large print if they have low vision. Children with low vision could also benefit from special devices that can increase the font of any book or document (Fig. 5);

- Canes: canes help children who are blind or have low vision move around in their environment, without running into things or people;

- Seeing eye dogs: the seeing eye dog will help the child who is blind or has low vision get to where he or she needs to be in as little time as possible (Fig. 6).

Figure 4. Braille book

Figure 5. Increasing font size

Figure 6. Seeing eye dog

Most children who are blind or have low vision catch with their peers in all aspects of life and development. They grow up to be healthy and happy adults who can hold full time jobs and live totally independently.

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment