2) In this lesson I say that our capacity for understanding or making meaningfulness from the first stories is seriously limited for numerous reasons and I briefly offer two reasons why this is so: 1) the social process of the telling is disconnected from the story and this creates obvious problems for ascribing meaningfulness, and 2) the extended time of criminal prohibitions against Indigenous peoples telling stories combined with the act of taking all the children between 5 – 15 away from their families and communities. In Wickwire’s introduction to Living Stories, find a third reason why, according to Robinson, our abilities to make meaning from first stories and encounters is so seriously limited. To be complete, your answer should begin with a brief discussion on the two reasons I present and then proceed to introduce and explain your third reason from Wickwire’s introduction.

This question asks us to elaborate on how our capacity for understanding first stories is limited. I will briefly discuss two reasons Dr. Paterson has provided, one being the disconnect from the social processes of storytelling, and two being the barriers imposed by cultural genocide. Considering both of these reasons, I will discuss a third reason which I believe has a similar effect on our understanding of first stories. The third reason I suggest is the salvage paradigm.

Before this course I didn’t know much about “first stories,” the stories told by Natives before contact with non-natives (and I still don’t know much), so my first introduction to these stories that have traditionally been told orally, were experienced through reading them in print and on a computer screen. Although I have never heard these stories told orally and therefore have nothing to compare it to, it seems to be clear that our capacity for understanding these stories are limited when they are experienced through a different medium than what they were originally intended for. I think that Wendy Wickwire, in her compilation of Edward Robinson’s stories, Living By Stories: A Journey of Landscape and Memory, recognizes this barrier and did a fantastic job at translating the stories that were told to her into a book format in a way that captures the quirks of storytelling that you don’t often see written down.

Another way our capacity for understanding these stories is limited is through the impact of cultural genocide. The Indian Act which was responsible for the initiation of a 75 year ban on potlatch ceremonies, where the first stories were traditionally told, as well as the implementation of the residential school system, both had severely detrimental effects on the tradition of storytelling. Years without opportunities for the storyteller to tell, or the listener to listen, has created a barrier or a gap in what our understanding of these stories can be today.

A third barrier that limits our understanding of first stories is one that I found in reading Wickwire’s intorduction. This third barrier has to do with the term the salvage paradigm. Being an art history major I’ve come across the term “salvage paradigm” in the context of art, but Wickwire made me aware that it also applicable to the treatment of First Nations stories.

As artist Janice Gruney discusses in her artist statement for her own exhibit titled “The Salvage Paradigm,” the term simply describes the “belief that it is necessary to preserve so-called ‘weaker’ cultures from destruction by the dominant culture”. This type of thinking is called up in Wickwire’s introduction when she brings up the work of ethnographers like Charles Hill-Tout and Frans Boas who only saw Native stories as having any value if they were pre-contact stories and had no “impurities” that suggested a post-contact historical setting (23). As Wickwire mentions, this type of thinking prevented the exposure of so many good stories that had non-traditional characters like cats, horses, and cows, and non-traditional elements like motor boats and guns. These stories were not pre-contact stories but they are important for the ways that they show how Native culture is not purely rooted in the past, but it is constantly changing and evolving.

The salvage paradigm seems to be the flip side of the detrimental effects of the indian act. Instead of ensuring the erasure of Native culture, the salvage paradigm fights to preserve it, at the risk of making it something that has no value in our contemporary society. Thankfully the salvage paradigm is something that has been resisted by museums, art galleries, and authors since the 1980’s, as Wickwire points out, and we have more or less moved past the dangerous thinking that brought about the Indian Act, however these barriers are not far enough in the past that they don’t effect how we understand Native stories today.

What do you think are some ways that first stories can be privileged more in our society?

Works Cited

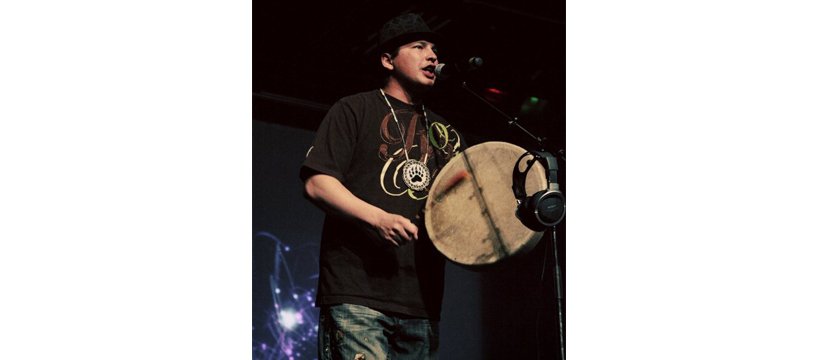

Grandish, Shaunna. Storytelling Important to Preserving History and Tradition. April, 2011. Photograph. Web. June 17 2016.

Gurney, Janice. “The Salvage Paradigm”. Panya Clark Espinal. 1990. Web. June 17 2016.

Robinson, Harry, and Wendy C. Wickwire. Living by Stories: A Journey of Landscape and Memory. Vancouver: Talon, 2005. Print.

Whiskeyjack, Tan’si Lana. “What are Oral Traditions?”. Native Drums. n.d. Web. June 17 2016.

Weiss, E. William. Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming/The Art Archive. Photograph. n.d. Web. June 17 2016.

Hi Natasha,

I loved your connection to the salvage paradigm. The link you provided offered a succinct description of the problematic system that Wickwire is criticizing in her introduction.

It’s interesting that often in our desire to “preserve” cultures and cultural artifacts (be it objects or stories), we do more damage than good. I understand the desire to record “history”. Museums are a great example of this. Even our own Museum of Anthropology is a storehouse for artifacts displaced from their original context in order to be preserved. But, when these artifacts are removed from their original context, they lose some of their meaning and significance. They become one-dimensional: tied to the story told on a plaque.

So in answer to your question, I think that we need to explore cultures, artifacts, and stories like we do the “round” characters in a narrative. Instead of assuming that Coyote [culture] can only be a “prankster/seducer”, we allow Coyote the freedom to be fluid, complex, multifaceted (Wickwire 27). We listen to what is said and not for what we want or expect to hear. And we refuse to “bracket” accounts that don’t fit with our imagined stories (13).

Does that make sense?

Janine

Hi Janine,

Thank you for your insightful response to the question I posed. I personally find it hard sometimes to figure out where my stance is on institutions like anthropology museums that have operated on the salvage paradigm. On one hand I strongly disagree with how these objects and artworks are removed from their original context and placed in glass cases that do a disservice to what they were traditionally meant for. However on the other hand I think that having these institutions available creates opportunities for the public to be educated on the different First Nation’s cultures in our country! I know that these days, a lot of museums and art galleries and publishing companies are working with First Nations people to ensure the proper treatment of their items and stories. You’re right that we need to read and understand these stories and the characters in them as “round,” as you said. The stories are adaptive, and always changing, like the people whom they belong to!

– Natasha

Hi Natasha,

This was the first time I heard the term salvage paradigm and I thank you for introducing me to it! I looked more into the paradigm and it truly is quiet fascinating, especially the relationship that our understandings have to first stories and what is often displayed in places of seemingly greater importance such as textbooks and museums. The very fact that the Western thought process is to save and preserve “weaker cultures” places them lower in a hierarchical sense. Personally I see this view as entirely crippling when one tries to understand past cultures and it cause confusion and distorts the truth of that culture. This may be a larger question to discuss, but what benefits do you think we could gain when we move away from such paradigms?

Best,

Navi

Hi Navi,

When I first heard about the salvage paradigm it really shook me up because I had never thought that the preservation of stories and traditional objects could be a bad thing! Of course, the salvage paradigm is a bad thing because it sends the message that the only “traditional” objects and stories have any value, which leaves no opportunity for appreciation of First Nations cultures today. I think that was a message that Wickwire was trying to explain in her introduction, by discussing all the stories that get left out when there is too much of a focus on the pre-contact stories. Your question is a big one, but its an important one! I think if I were to narrow it down I would say there are two main benefits of moving away from the salvage paradigm. The first is that the reader can gain a better understanding of how stories are adaptive and changing just like the people that they belong too! When we realize that First Nations stories can have modern elements to them, it challenges the stereotype that First Nations cultures are stuck in the past. A second benefit is that it gives the First Nations people a voice in the world of literature, and gives them agency in how their stories are told. Many institutions these days like publishing houses, museums, and art galleries are aware of the dangers of the salvage paradigm, so its common for First Nations people to have a greater control over how their culture is represented, however its still something that has to always be considered. As far as we’ve come we still have to be conscious of these things! Thanks for your question!

– Natasha

Hi Natasha,

Sorry for the later response – I’m just catching up on my blog comments now 🙂

Like Navi, this is the first I’ve heard of “salvage paradigm” and I’m really glad that you’ve enlightened my on a word to articulate that phenomenon I’ve seen so often as a First Nations and Indigenous Studies major. I oftentimes find that white culture is so much about “saving” things, whether that be languages they do not ancestrally speak or artifacts (like Janine mentioned) in museums.

For me, it all really comes back to the ethnocentricity of white academia and the prioritization of salvaging certain things when white academics become interested in them (for whatever reason). This is obviously not all with malicious intent, and there are some fantastic settler scholars that work intimately and in trusting relationships with Aboriginal communities, but the purpose behind the “salvaging” is so displaced it can be very harmful.

I’ve recently read a book called ‘Indigenous Methodologies,’ by Margaret Kovach that talks about how non-Native researchers and academics can work with Indigenous communities in “a good way” and be able to remove Western ways of learning that cause so much harm to Aboriginal communities. One point that really stuck out for me is the cruciality of contextualizing your personal self to your work. I think Western academics approach work in Aboriginal communities from their idea of “professionalism” and that means keeping who they are a secret. This is completely contrary to how knowledge is gathered in most Aboriginal settings that are so inherently familial.

I wonder what your opinion is on how contextualizing yourself (who your family is, your ancestry, where you come from) can help to avoid the “salvaging paradigm”?

Thanks!!

Heather