MEXICO: A Sinking City

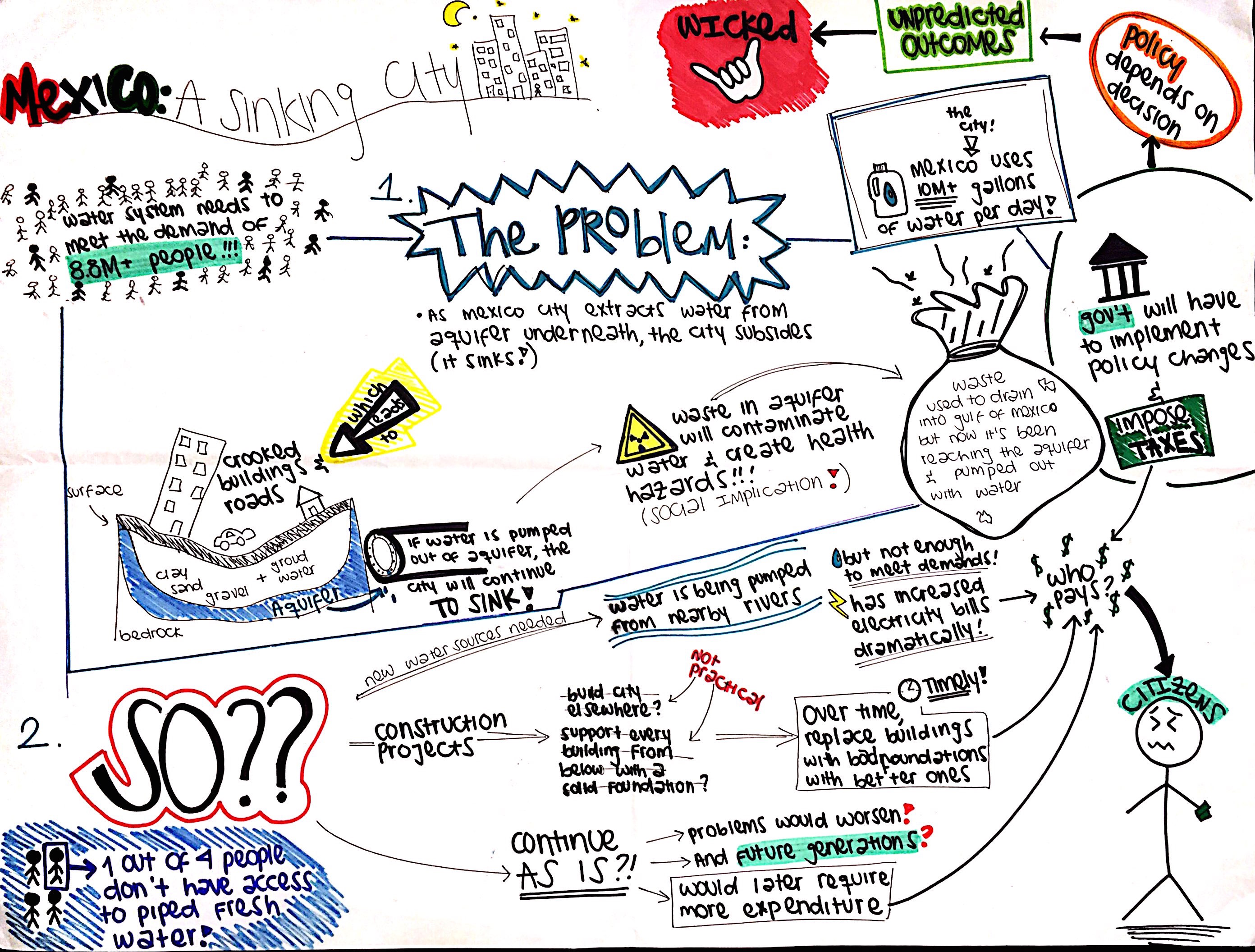

Mexico city is sinking quickly. In fact, it has sunk more than 10 meters in the last hundred years (Sample, 2004). To come to understand why this problem is a wicked one, one with no apparent solution, we must really sink into it (pun intended) and explore its contradictory and complex implications. This city is a megacity with over 8.8 million inhabitants all of whom rely on its infrastructure, water sources, policies, and environmental conditions. Not foreseeing the growth of the city, the Aztecs built the city in an island amid a lake and some years later the Spaniards drained the lake to expand as the city grew. Wells were dug into the clay-laden ground to extract water from underground aquifers. As water is extracted the clay compresses, and this compaction is not reversible (Rudolph, 2001).

In a city that uses more than 10 million gallons of water per day (Sample, 2004), the massive extraction of water has caused million-dollar damages to the infrastructure including buildings, water pipes and sewer lines, subway tunnels and roads (CNN, n.d.). In fact, one in ever four people does not have access to piped fresh water and have to rely on foul water distributed weekly (Marshall, 2005). Additionally, as the distance between where the waste is being disposed of and the aquifers decreases and some drainage canals no longer flow downhill, instead of draining into the Gulf of Mexico this waste is making its way into the underground water contaminating it and posing health hazards to the millions that depend on it (Sample, 2004). To reduce the stress on the aquifer, water is being pumped from nearby rivers (Sample, 2004), but this source is not enough to meet demands and the city continues to sink. To aggravate the situation, pumping the water has increased electric consumption and hence electric bills dramatically. Thus, a problem that at first glance would be easily solved by not pumping water from the aquifer becomes wicked when alternative water sources are scarce and rampant water consumption continues.

Moving the city elsewhere is not a feasible solution, but neither is replacing every building’s foundations with more solid ones. Replacing buildings over time for ones built with this problem in mind is timely let alone costly. On the other hand, ignoring the problem is barely an option as problems would only worsen and the required expenditure would escalate exponentially. Besides, Mexico City lies near a fault and is prone to earthquakes, which often lead to very high mortality rates due to the city’s unsafe infrastructure (Johnson, 2011).

Seemingly, the best solution would be to stop using the wells altogether, but in addition to posing economic and structural pressures, this measure would create a strong conflict of interests. Closing the municipal wells, which have been dug deeper than the private ones would be easier from the administrative perspective and would not meet the opposition of the powerful owners of the private wells. However, closing the shallow private wells would help stabilize ground pressure faster (Loehnberg, 2015) but this has been met with resistance.

Given that the problem cannot be ignored, the government will have to implement policy changes such as the re-utilization or allocation of water as well as impose taxes to pay for the necessary construction and reparations adding to public opposition.

The further one looks into the problem, there more one realizes that every possible solution has significant consequences and can lead to unpredicted outcomes with profound social, economic and environmental implications.

References

Johnson, Tim. “Mexico City Copes with That Sinking Feeling.” The Seattle Times. N.p., 24 Sept. 2011. Web. 25 Sept. 2015. <http://www.seattletimes.com/nation-world/mexico-city-copes-with-that-sinking-feeling/>.

Loehnberg, Alfred. “Aspects of the Sinking of Mexico City and Proposed Countermeasures.” American Water Works Association 50.3 (1958): 432-40. Web. 25 Sept. 2015. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/41255126>.

Marshall, Claire. “Mexico’s Sinking City.” BBC News. BBC Mexico City, 08 Dec. 2005. Web. 25 Sept. 2015. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/from_our_own_correspondent/4508062.stm>.

Rudolph, Meg. “Sinking of Titanic City.” Geotimes. Geotimes, July 2001. Web. 25 Sept. 2015. <http://www.geotimes.org/july01/sinking_titanic_city.html>.

Sample, Ian. “Why Is Mexico City Sinking?” The Guardian. N.p., 6 May 2004. Web. 25 Sept. 2015. <http://www.theguardian.com/science/2004/may/06/thisweekssciencequestions>.

“Sinking Mexico.” CNN Student News. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, n.d. Web. 25 Sept. 2015. <https://go.hrw.com/math/cnn/course3/3_1_Sinking/3_1_Sinking.htm>.

Data Sourcing and Assessment

Framework questions for the analysis of wastewater management:

- How has land subsidence affected wastewater management?

- How are wastewater management practices responding to increasing land subsidence?

- What are the implications of these wastewater-related issues for the health of Mexico City’s population?

Academic Journals (4)

- Gaytán, M., Castro, T., Bonilla, P., Lugo, A., Vilaclara, G. 1997. Preliminary study of selected drinking water samples in Mexico City. Revista Internacional de Contaminación Ambiental, pp. 73-79.

This article for the Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal, sought to obtain data on drinking water from 24 of the 27 Municipal Districts in the city by gathering samples from “municipal network intakes, cisterns, roof tanks, and kitchen tap water” (73). The study gathered 209 samples and gave a detailed account of numerous physico-chemical parameters and “biological analyses of total and fecal coliforms” (73). Produced by the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), this source could provide a comparison between results analysed within the country and results gathered by international scholars who have less direct political and other stakeholder pressures. For example, when compared to the article by Mazari-Kriart et al. (1999)(see below), this article found that water quality was good in 53% of the cases and attributed the polluted water within households to poor domestic handling. This same characteristic is a possible weakness, as results might be biased towards conforming to stakeholder interests.

- Mazari-Kriart, M., Torres-Beristain, B., Velázquez, E., Calva, J.J., Pillai, S.D. 1999. Bacterial and viral indicators of fecal pollution in Mexico City’s Southern aquifer. Journal of Environmental Science and Health. 34(9).

This source is an article for a renowned academic journal. It seeks to reveal “the extent of microbial pathogen contamination” (1715) of the groundwater reserves on which Mexico City depends on to meet 70% of the water needs of more than 18 million people. To do so, the researchers monitored the southern aquifer for 10 months and obtained water samples to analyze for fecal microorganisms, most of which are infectious and thus constitute important health hazards. It is important to consider that this source was written over 15 years ago, and thus some information might be out-dated as new management practices and technologies are developed. The article presents extensive data analyses and discusses possible sources of error. Its results reveal that the largest number of samples were bacteriophages were found coincide with the wells where “most of the recharge to the aquifer system occurs” (1728) and that the number of fecal coliforms exceed the limits in Mexican drinking water standards several times in all of the studied locations. These findings provide valuable information regarding the effects of contamination of the water sources by wastewater and thus are important for answering the questions in focus.

- Saade Hazin, L. 1997. Toward more efficient urban water management in Mexico. Water International. 22:3, pp. 153-158. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02508069708686694

In her academic article for the Water International journal, Saade Hazin discusses the state of the water sector in Mexico City while focusing on its legal and institutional framework, the difficulties faced by the municipalities, and the four main policy changes proposed by the government, which include “changes in the legal and institutional framework for water management, further decentralization, new financing schemes, and greater private sector involvement,” and proposes approaches to reach appropriate solutions. Although not specifically focused on wastewater and its management, this article provides information on policies that directly respond to and affect the issue at hand. The author explores the health costs associated with the water system (around US$3,600M), which include those of diarrheal diseases caused by water and soil pollution, food poisoning, and the lack of sanitation. Additionally, she mentions the importance of increasing wastewater treatment capacity to satisfy increasing water needs.

- Sosa-Rodriguez, F.S. 2012. Assessing Water Quality in the Developing World: An Index for Mexico City, Water Quality Monitoring and Assessment, Dr. Voudouris (Ed.), InTech, Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/water-quality-monitoring-and-assessment/assessing-water-quality-inthe-developing-world-an-index-for-mexico-city

A peer-reviewed chapter for a book with numerous academic contributors, this source provides detailed information on how waste in Mexico City is managed. It focuses on the city’s poor water quality and argues that “untreated wastewater discharge to freshwater sources” and “runoff from wastewater reuse for crop irrigation” (496) are significantly detrimental to water quality and consequently to human health. The source is particularly important to the theme being explored as it explains how land subsidence has exposed groundwater to direct pollution caused by wastewater and how this subsidence has broken water and sewage pipelines and caused wastewater flooding. The source cites a large amount of scholarly articles and provides useful statistics such as only 9% of the wastewater being treated while the other 91% is discharged without any treatment. Having the whole of Mexico’s water system as scope, this source provides a context as to where the water comes from and analyses other health hazards.

Grey Literature (2)

- Hollander, K. 2014. Mexico city: water torture on a grand and ludicrous scale. The Guardian. Available from: http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/feb/05/mexico-city-water-torture-city-sewage

This article was written for a distinguished online newspaper; as such, this source is reliable due to its wide readership. Written in first person and colloquial language, this source provides a firsthand account of a resident of Mexico City who states that ‘the disposal of human sewage has always been a major problem.” It comments on the origins of the issue, dating as far back as colonial times where canals and rivers were used as dumping grounds and mentions the three main sewage works built in 1789,1900, and 1975 as responses to the City’s growing population and the increased stress on its wastewater systems. This reference will be useful for the scope of this research as it follows wastewater from its source in the city to the Mezquital Valley, where most of the City’s human waste is sent. An arid region with no water supply of its own, the valley has used this raw sewage to irrigate almost 40,000 acres of cropland, a practice that could be a theme in its own given its disputed implications for health hazards. Additionally, this article makes reference to events such as ‘the great black flood’ in which over 60,000 inhabitants of a neighbourhood were affected by wastewater floods, which could be other points of analysis.

- Jarman, J. 2015. Aguas Negras: Mexico City’s Water problems. Videography, Photography and interviews. Available from: http://janetjarman.com/portfolio/view/aguas-negras

With over 53 publications in sources like National Geographic and the New York Times and over 36 awards and honours, Janet Jarman’s explicit photography address problems like regular flooding, aging and “damaged infrastructure that can no longer cope with wastewater volumes, subsidence caused by aquifer overexploitation, and the disparity between those with access to water and those without.” The video contained herein documents the dilemma of using the sewage water that is dumped into the state of Hidalgo to irrigate fields of produce for human and animal consumption. This, of course, is the source of numerous health concerns, but some farmers argue that fertilizing the crops otherwise would be too costly and others go as far a saying that this practice has never affected their own health. This reference’s weakness lies in that it is subject to the reader’s interpretation but it also provides a more vivid account of the extent of the issue giving it a more human and less statistical perspective.

Raw data sources (2)

- UN-Habitat. 2003. Water and Sanitation in the World’s Cities: local action for global goals. Earthscan. Available from: file:///Users/usuario/Downloads/1150_alt.pdf

A report by the United Nations Human Settlement Programme, this source provides raw data on aspects of wastewater management like the percentage of the population that is connected to the sewer system of various cities in Latin America, including Mexico City. In addition to providing useful statistics to validate claims on wastewater management in Mexico City, it allows for comparison between other cities in the region. One table in this source shows, for example, that 9.87% of the City’s population is not connected to its sewer system and of that percentage, 89.1% have no connection or drainage system whatsoever. As a document for the United Nations, this source focuses and water and sanitation mostly in developing countries, and thus places more emphasis on data produced by country rather than focusing on Mexico City itself. It does, however, highlight the City’s subsidence as a problem for wastewater management as sewers and other structures have been weakened and “pumping has been required to lift drainage water that used to flow by gravity” (141).

- National Research Council Staff, Academia de la Investigación Científica (Mexico), & National Research Council (U.S.). 1995. Mexico city’s water supply: Improving the outlook for sustainability. National Academy Press. pp.19-40.

This book was the result of a study conducted through a nongovernmental partnership between the US National Research Council and the Mexican Academies of Science and Engineering. It addresses the technical, health, and social implications of ground water extraction, water demand, and the quality of the available water in Mexico City’s metropolitan area. Equipped with various tables and figures, the book provides detailed lists of wastewater reuse applications and the concerns associated them, such as “public health concerns related to pathogens” (35) and the marketability and acceptance of crops irrigated with wastewater. It also puts forth a list of wastewater treatment plants within the state of Mexico, for example. Due to its detailed analyses on the data presented, this source could be used more extensively as grey literature as it contains additional information that could contribute to the analysis of the present theme.

Follow

Follow