Fifteen years after the Iraq War began, Magnum photographers are reflecting on being embedded with the U.S. military and how it affected the work produced during the conflict. While the practice of embedding journalists is not new it very much came to the public’s attention during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, estimates are there were 700+ journalists and photographers embedded with American military troops.

There is much controversy about this practice, some of which is highlighted in the Magnum photographers reflections. A key issue is the sympathetic and dependent relationship with the military, one that lead to what some journalists referred to as propagandizing.

We were a propaganda arm of our governments. At the start the censors enforced that, but by the end we were our own censors. We were cheerleaders. Charles Lynch

Primary issues are:

objectivity: embedding potentially makes journalists tools of the military whose access and message can be manipulated and controlled; provides an insider view of military life; doesn’t allow for access to life in the context, the life of those against whom war is waged

access: embedding provides journalists with access in otherwise unsafe contexts

What does this have to do with research?

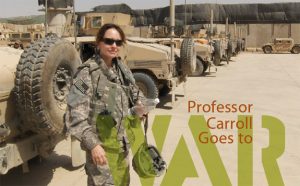

The same embedding strategy was used for anthropologists and other social scientists. Since 2007, the Pentagon’s Human Terrain System (HTS) started placing social scientists in every Army combat brigade, regiment and Marine Corps regimental combat team in order to improve the Army’s cultural IQ. The HTS has now been phased out, not because of ethical issues but because there were insufficient on the ground troops to warrant the program. Indeed, the protests of professional associations had little impact on the existence of the HTS. This article is a good summary of the HTS.

The same embedding strategy was used for anthropologists and other social scientists. Since 2007, the Pentagon’s Human Terrain System (HTS) started placing social scientists in every Army combat brigade, regiment and Marine Corps regimental combat team in order to improve the Army’s cultural IQ. The HTS has now been phased out, not because of ethical issues but because there were insufficient on the ground troops to warrant the program. Indeed, the protests of professional associations had little impact on the existence of the HTS. This article is a good summary of the HTS.

It is important to note, collaborations between social scientists and the military did not begin with Iraq, but have always been controversial. For example, Project Camelot, a program intended to help the U.S. Army assist friendly Latin American governments in dealing with insurgency as well as influence social and economic development, didn’t survive once it became public.

Nonetheless, it is useful to ask what has been learned?

- The ethical dilemmas presented by embeddedness are significant. Basic premises of informed consent are by definition ignored and violated.

- It is critical to ask how the methodological and value traditions of social science might be compromised/affected by the invitation to participate by one side of the conflict in a military zone. Will cultural knowledge be used against those in the invaded country/region, for example? Is the work meant to create knowledge or intelligence? What is the relationship between social science and politics?

- What are likely consequences the work will be controlled by the military, in other words, what is the likelihood of becoming a legitimation of propaganda?

These questions remain relevant because, at least on the military side, a desire to use the knowledge and skills of social scientists is still deemed useful, and there is the possibility the HTS has been reinvented under a new name, the Global Cultural Knowledge Network.

Follow

Follow