A challenging idea for many graduate students learning how to do interpretive and critical research is that one must make a commitment to a research methodology. The two most common errors/scenarios are that students want to begin with research methods (ways of making and analyzing data) or research design features (the most common is to say they want to do a case study, a topic I discuss in some detail here.)

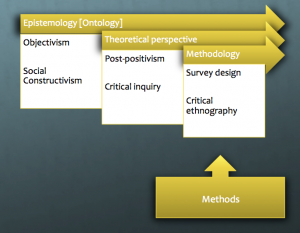

I find Michael Crotty’s definitions and relationships among the elements that frame research helpful. See this image and here, for a short note on this.

I find Michael Crotty’s definitions and relationships among the elements that frame research helpful. See this image and here, for a short note on this.

A methodology is a framework that contains core ideas reflecting more fundamental epistemological and ontological groundings, but it also provides guidance on the focus of our inquiry, key concepts, values, and often a hint at methods (although this is a separate matter). A methodology contains core definitional foci and cue us to what to expect in a research project. Methodologies also give us a sense of what we might expect the outcome/product of the research to be, even though there is tremendous variation in representational forms within any methodology.

To help students understand what a methodology is and why we need one, I use the metaphor of methodology as recipe. A recipe is a framework for preparing food: it has a name that reflects what the outcome will be; a list of ingredients, procedural guidelines; tools and techniques; and often a color photo to show us what the food should look like when we are finished. And, different recipes illustrate fundamental differences. For example, a recipe for a chocolate cake and one for beef stew vary on all of these features and are therefore about something quite different. One would never follow a recipe for a chocolate cake and expect to end up with beef stew.

Chocolate Cake Beef Stew

flour, sugar, cocoa, eggs, butter beef, broth, carrots, potatoes, onions

whisking, stirring, mixing chopping, browning, deglazing

mixer, cake pan, whisk knives, heavy pot

baking braising, stewing

A methodology is a framework for doing research: it contains a name that reflects the outcome; what is needed to identify the research as being within that framework; procedures and tools; and we often have a general notion of what the outcome will look like.

Ethnography

culture, language, rituals, artifacts

field work: prolonged engagement, participant observation, interviewing, kinship charts, mapping, SNA

field notes, photographs, transcripts

thick description; analysis with cultural categories; emic perspective

Novice cooks and researchers are more likely to follow recipes closely, developing the knowledge and skills that will in time free them from a specific recipe while still working within the recipe framework. A good cook might substitute Guinness beer for some broth in the beef stew, but she is still making beef stew. An ethnographer might substitute live field note taking using social media for more traditional field notes, but she is still taking field notes.

Without a methodology a research project is ungrounded, drifting and has a high probability of being atheoretical. With a methodology, with a recipe, the researcher plans on making an ethnography or a narrative analysis or a hermeneutic investigation because the core ideas, the ingredients, the tools are valued and indeed reflect deeper senses of the nature of both the world and knowledge about it.

Follow

Follow

Thanks for the clear and wonderful meaning of methodology, i have a problem understanding a clear meaning of phenomenological and positivism research any help.

I’m glad this post was useful for you. I recommend Michael Crotty’s book, The Foundations of Social Research, to clarify the meaning of phenomenology and positivism/neo-positivism. Also, Max Van Manen’s website Phenomenology Online is a free and rich resource.