The many guises of mixed methods…

Mixed methods are used when there are two or more types of:

Mixed methods are used when there are two or more types of:

➢ research questions

➢ sampling procedures

➢ data collection procedures

➢ data

➢ data analysis

➢ conclusions

It is relatively easy to mix methods at the methods level, i.e., when the intent is to collect both quantitative and qualitative data. This can be accomplished within a single method. For example, you might use observation as a method and use an inventory to record frequency of behaviours, interactions, and so on. You could also record dialogue or take field notes occurring during this same observation. But this strategy may also mean using a method that generates numbers (likert scale item survey) and a method that generates words (oral history interview).

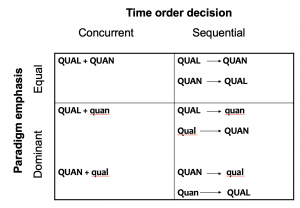

With mixed methods often one or the other paradigm is primarily emphasized and often there is a sequential use of one then the other paradigm. This chart illustrates possible variations.

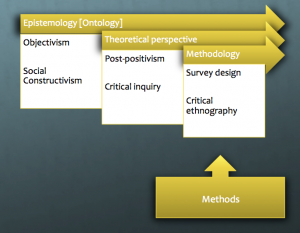

Mixed methods research wants to move beyond this simple distinction of types of data and the field makes an effort to elevate the idea to a methodology, even sometimes crossing the epistemological boundaries of objectivism and social constructivism. A research study that uses interviews and participant observation, for example, is now not necessarily considered mixed methods research. Whereas, a research study that uses hermeneutics and times series analysis would be a mixed methods study. These different contexts also suggest the “mixing” can occur at different places within the research process.

Justification for mixed methods…

A primary justification for mixed methods is pragmatism. (Read, for example, David Morgan’s argument for this justification here.) Pragmatism asserts no first or foundational principles and suggests that all human knowledge is empirical, what John Dewey called “empirical metaphysics.” I confess to being unclear how the philosophical position of pragmatism is a justification for mixed methods—how does the primacy of experience lead to any particular methodology or method? And, is this a confusion of pragmatism with being pragmatic?

Related to this pragmatic justification is the triangulation justification, especially more contemporary notions of triangulation that focus on the complementarity and complexity added by multiple data sources, analyses, and so on. See my discussion of triangulation along these lines here.

Feyerabend’s “anarchist epistemology” might also justify mixed methods, either within the same study or across studies of the same or similar phenomena. This is in the big picture a more dialectical approach, working iteratively across paradigms rather than necessarily combining paradigms.

To justify mixed methods, one must at some level reject the incommensurability argument, i.e., the argument that the differences in epistemological theories cannot be overcome. (Note that the incommensurability argument at the level of the unit of measurement is easily overcome.)

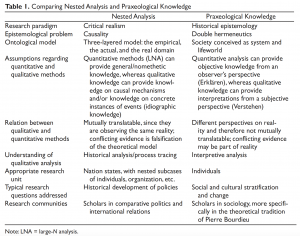

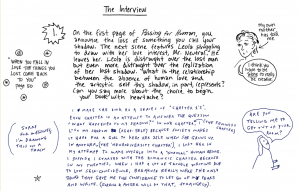

In this article, Sommer Herrits’ illustrates two mixed methods (nested analysis and praxeological knowledge) approaches that operate at the paradigmatic level and result in substantially different emphases. I’ve included her summary comparison of the two approaches below.

Here are some additional resources for further exploring mixed methods…

Bergman, M. (2008). (Ed.) Advances in mixed methods research: Theories and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. & Plano-Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Greene, J.C. (2007). Mixed methods in social inquiry. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Journal of Mixed Methods Research

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (2010). Handbook of mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

And here is a good example of a study using mixed methodology…

Castro, F. G., & Coe, K. (2007). Traditions and alcohol use: A mixed-methods analysis. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(4), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.269

Follow

Follow

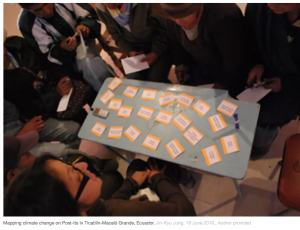

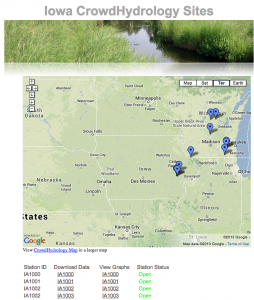

“The CrowdHydrology mission is to create freely available data on stream stage in a simple and inexpensive way. We do this through the use of “crowd sourcing”, which means we gather information on stream stage (water levels) from anyone willing to send us a text message of the water levels at their local stream. These data are then available for anyone to then use from Universities to Elementary schools.”

“The CrowdHydrology mission is to create freely available data on stream stage in a simple and inexpensive way. We do this through the use of “crowd sourcing”, which means we gather information on stream stage (water levels) from anyone willing to send us a text message of the water levels at their local stream. These data are then available for anyone to then use from Universities to Elementary schools.”