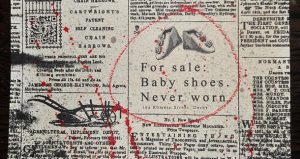

Six word stories have been around for many years now, instigated by Hemingway’s six word story, the title of this post. (Caution: there is dispute about this authorial attribution, but I’ll take the story at face value here.) Hemingway’s story contains three elements, a 2-2-2 form. (Another common form is 3 -3 and these forms contribute to the aesthetics of the story.) The first “for sale” calls to mind a recognizable trope, followed by “baby shoes” a recognizable object, but it is the third element that turns this into a story. “Never worn” can invoke many possible meanings, but perhaps most common is the tragedy of child loss. Those baby shoes were never worn, because the baby wasn’t there to wear them.

These examples from reddit show the continued  appeal of this genre, and the claim is this is a new genre. A collection of six word stories can be found at Six Word Stories sorted by category. An off-shoot of six word stories is Six Word Memoirs. Most six word stories are published on the internet, rather than in books or journals.

appeal of this genre, and the claim is this is a new genre. A collection of six word stories can be found at Six Word Stories sorted by category. An off-shoot of six word stories is Six Word Memoirs. Most six word stories are published on the internet, rather than in books or journals.

In The Poetics of Six-Word Stories, David Fishelov provides a cogent analysis of six word stories as a genre. He identifies seven (alas not six) features of six word stories:

- a chain of events

- something implied

- punch line structure

- poetic/rhythmic structure

- realism

- contagiousness of the form (you will want to write one too)

- predominately a genre in English

Six word stories have only one explicit rule… that they be six words. But looking more analytically at these stories they also seem typically to require something implied, something not explicitly stated in the story… the possible death of the baby in Hemingway’s story. This very short story form has a contemporary appeal in an age of texts, memes, and tweets.

Many six word stories are primarily about the aesthetics, but as the reddit examples illustrate they are also stories filled with meaning and the telling is heart-felt. There are plenty of pedagogical uses of six word stories, but they may be useful in research, especially narrative research. From a research perspective, whether six word stories are literature is less important than whether they provoke reflection, illustrate human experience and meaning, and perhaps whether they are a window through which we can see other stories.

While six word stories stand alone, they might also be prompts for more discussion of experience and meaning… a beginning to a more elaborated story.

Six words, only six words, alas.

Follow

Follow