Theseus. The catacombs were labyrinthine, like twisted entrails. In its descent the decryptionist lost its bearings, all reference to an exterior reality. And yet this was more than a free-fall down the rabbit hole. The eerie maze into which the creature delved obliterated distinctions between aboveground and below. The red string that would guide it through the corridors led not to an exit but to the heart-chamber of the complex: an ambiguous center at best. A library, an archive, its walls carved with niches, each bearing a scroll. The decryptionist felt a vague sense of transgression, a voyeur in the minotaur’s den. It unrolled each vellum text, caressed the ciphered words. Its task could begin.

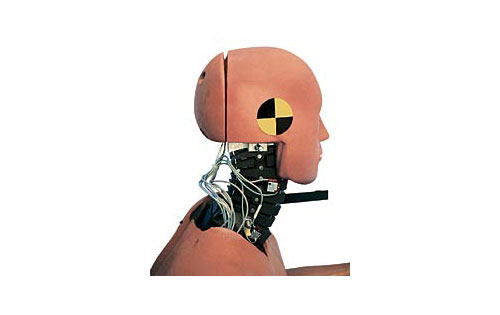

Biomechanoid. Newel stirred cream and honey into his coffee and brought up the discordant array of windows on the dusty LCD screen of the aging computer. ‘The Atrocity Exhbition attempts to vivisect its cultural moment by dissecting the past or memory of a surreal and quasi-speculative future,’ Newell wrote. ‘Its structure resembles both a disjointed cityscape or unfathomable machine and a fragmented human body, a fleshscape, as confused and dismembered as a mutilated anatomical textbook whose spine has decayed and whose pages have been shuffled like a pack of sallow and near-pornographic tarot cards – the Pudenda, the Abdomen, the Ulcerous Lip, the Radiation-Seared Thorax. And yet, as it collapses real and imaginary into the single undifferentiated phantasmagoria that is the Baudrillardian hyperreal, the text fuses these two parallel metaphors into a machine-flesh hybrid, an erotic cyborg, as fetishized and grotesquely appealing as a Giger Biomechanoid – thus the prevalence of the billboard-labyrinth, the malformed sculpture gardens, and above all the car-crash. The world of The Atrocity Exhibition is not a straightforward escape as in a dream narrative but a psychosis in which real and unreal/imaginative are rendered miscible and indeed indistinguishable. To quote, Andrzej Gasiorek’s Deviant Logics, “…this fragmentation of the prosaic world, which blurs the boundary between fantasy and reality, creates a liminal space in which memories begin to stir” (63). The breakdown of distinctions between organic and inorganic mirrors the more fundamental deconstruction of the Real at the heart of the text.’

The Nectar of Exegesis. Clippings from the text hung from clothes-pegs like developing photographs in some proto-cyberpunk pornographer’s darkroom. Others were plastered against the walls of the tomb-like subterrane, overlapping with pages culled from medical dictionaries and coffee table books of surrealist painters, with esoteric critical texts. The decryptionist flitted about the secular sepulcher, hovering at some particular constellation of words and images, a quizzical clockwork hummingbird. Early on it had decided that the cipher, the ambrosial nectar of deconstruction, would never be extracted through a linear reading. It inhaled the heady perfume of its efforts with detached pleasure.

Moulting. ‘By depicting its atrocities as endlessly repeated, the text transmutes their raw horror or shock value – their affective capabilities – into a kind of numbed and detached nausea.’ Newell flickered between screens, a morass of information. He sipped at his third cup of coffee. ‘This is intrinsically connected to the breakdown between real and imagined. The Atrocity Exhibition is commenting on the capacity for the media to not only desensitize its consumers to depictions of violence but to transform our entire relationship to representation itself, to “mimetization.” Authenticity becomes not so much disputable as unimportant through the lens of the text, just as the difference between dream-world and real-world collapses for the reader as the protagonist’s psychosis (“simulation”) develops. As we explore the catacombs of the text we gradually come to inhabit this disaffected space, becoming ourselves mechanistic, shedding layers of shock and perturbation and metamorphosing into something both more and less than human.’

Troglodytic Knot-Tying. The Atrocity Exhibition’s peculiar algebra could only be understood through a more complete subsumption into its baroquely chaotic quasi-narrative; yet even complete immersion inevitably failed to distill the book into a wholly comprehensible form. Variables in its intricate formulae remained unsolved and numinous. The decryptionist gnawed at fraying strands of meaning in the muted barrow-light, tying together knots of texture and imagery and then watching its configurations unravel.

This is my critical response – a pastiche/homage of the book, hopefully with some critical engagement. Matthew, if this isn’t what you’d envisioned, let me know and I’ll write up something else, and this can just be an example of my pretentious pseudo-creative writing.

Works Cited

Ballard, J.G. The Atrocity Exhibition. Great Britain: Flamingo, 1993.

Gasiorek, Andrzej. “Deviant Logics.” Contemporary British Novelists: J.G. Ballard, 58-80. http://books.google.com/books?id=wAsri-PTseQC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Andrzej+Gasiorek,+JG+Ballard&ei=TL2DSeDyOIPIlQST4vXuBQ#PPP1,M1, Feb. 7.