Sitting in Vancouver ’s CKNW studio, about to be interviewed live on the Bill Good Show, Jorge Amigo must have wondered how the heck he ended up here. Five years before, he had moved to Canada ’s west-coast urban gem from his home of Mexico City to study political science at the University of British Columbia. Now Amigo was staring down on Vancouver from the 16th floor of the elegant and corporate Pacific Centre tower preparing to speak to thousands of his Lower Mainland neighbours live on air. He hadn’t expected much when he whipped off a response to a gender-polarizing article, “Do Vancouver Men Suck,” written about the local dating scene and published in Vancouver magazine on January 1,2012. That article, however, was met with lots of controversy and now the same magazine had turned Amigo’s rebuttal – “Do Vancouver Women Suck?” – into a follow-up article in which he argued that the city’s women are paranoid and anti-social, as exemplified by the explosion of panic the moment a man (who did not go to elementary school with them) talks to them. And according to Amigo, those same women who have perfected the ice-wall exterior seem to be the ones who have written the book on dating in the city. That article in turn landed Amigo on the region’s most listened to radio talk show.

Amigo settled into his seat, wanting to shift the conversation away from the gender debate and focus on the atmosphere that created this discussion in the first place. His basic thesis: Vancouver is an unfriendly city, period.

Amigo stated that there was an air of isolation about the city, making it hard to socialize here. To which Good, live on air asked, “So what are you going to do about it?” In that moment, an idea sprang to Amigo’s mind. “Why don’t we do a flash mob? … If you’re listening and you agree with me, let’s meet tomorrow, 7 p.m. at Robson Square.”

He came up with the name and hashtag #bemyamigo, pretty much on the spot and sent a bunch of tweets to follow it up. Suddenly Amigo had assigned himself the responsibility of making Vancouver a friendlier city. Now all he needed was for people to show up.

The next evening about 25 strangers arrived at the allotted time in Robson Square and, after some wide-eyed surprised handshakes and friendly hugs, the group decided to head over to Caffé Artigiano across the street for a drink and a chat. 6 And Amigo saw that just maybe he could be the driving force to inspire some beautiful friendships.

Disconnected and Disengaged

But that inspired jump into creating a friendlier city had all happened about nine months before I had heard anything about it. One evening in September 2012, I had joined the throng of UBC students at Calhoun’s Bakery Cafe – the 24-hour study cafe on Kitsilano’s West Broadway strip, bursting constantly with students on their laptops – when I met Nicole from Wisconsin. She had been living in Vancouver for the better part of 14 months and was feeling a bit lonely in her new city. We struck up a conversation amidst the interesting mix of people working away at the busy cafe, most of whom were connecting with technology, much more so than with their neighbours.

I find Vancouver kind of a tough place to meet people. It’s kind of a cold city that way, Nicole said. She told me she was considering going to another meet-up group, where people of all sorts come together with the common desire of seeking further connections in their given interest group or community. But she said her previous experience was terrible so she was hesitant to try it again. When I inquired about the nature of this potential new group, she said it was called “Be My Amigo,” run by a guy named Jorge Amigo. I was immediately intrigued.

I also began giving serious thought to what Nicole had said earlier about Vancouver lacking warmth among its people, and reflected on how many times I had heard similar comments from other newcomers. I can recall experiencing a bit of loneliness myself upon first arriving a little over a year earlier. Now I was beginning to wonder whether those collective feelings were indeed the standard adjustment woes of moving to a new city or was this a problem belonging distinctively to Vancouver? I was determined to get to the bottom of it.

–

Jorge Amigo and Nicole from Wisconsin are far from alone in their perception of Vancouver ’s icy temperament. In fact, their feelings are on par with what more than 100 respected community and government leaders, business people and academics felt when polled last year regarding what ails Vancouver.

The difference is that Amigo – whose name, yes, means “friend” in Spanish – is actively trying to do something about it. Last spring he started a bi-weekly networking event called Be My Amigo, where he invites about 30 to 40 perfect strangers to meet and socialize with each other in an informal setting at one of two Vancouver venues. His hope is that these events will begin to break down the perceived social barriers that Vancouverites have either built up for themselves or fallen into as a result of the city’s unfriendly culture. “My vision is that this will become a movement, not just about the events that I organize but simply an ethos.”

Catherine Clement is the former vice-president of public engagement and communications for the Vancouver Foundation. She knows a thing or two about what it’s like to feel unwelcomed. Sitting in her beautiful 12th-floor office on Seymour Street in downtown Vancouver, complete with a jaw-dropping view of Burrard Inlet, she shared with me her experiences of returning to her birthplace of Vancouver 12 years ago from Toronto, where she had spent most of her adult life.

“We came here for work and everybody knew we were from somewhere else. Yet we spent the first nine months without a single invitation from anybody for coffee or drinks or dinner, to tell us anything about the community.”

She contrasts that with a story of her best friend, who moved to St. John’s, Newfoundland around the same time as her move to the West Coast. “On the second night after she arrived, she sent me an email telling me how she went to the corner grocery store to pick up eggs and milk, and the clerk there invited her and her husband over for dinner that night and talked to them about St. John’s and what they should see and do. That’s the difference.”

Clement was one of the architects of a recent Vancouver Foundation survey of 3,841 people that painted the city as a network of strangers: one-third of respondents said they consider the city a tough place to make friends and one-in-four reported feeling alone more often than they would like. Many don’t care to meet their neighbours, nor volunteer or mingle outside their social or ethnic group. These results substantiate Vancouver’s reputation for “coldness” referenced in multiple articles, blog posts and city reviews. In 2012 when HSBC surveyed more than 600 immigrants across Canada about their relocation experience, Vancouver drew the lowest rating of any city. Also considered is a 2010 Angus Reid poll that indicates Vancouverites are more addicted to social media than residents of any other Canadian city, but felt among the least connected to friends and family.

This prompted a five-part series in the Vancouver Sun last summer entitled “Growing Apart.” According to Clement, Sun editors told the Vancouver Foundation they were amazed at how much commentary the topic generated. The survey was also one of the driving forces behind a large-scale community initiative from Simon Fraser University held in September. The inaugural SFU Public Square Community Summit included 11 special events throughout six days with themes of sparking and restoring community connections while raising conversations about this growing issue of public concern.

The methodology behind the Vancouver Foundation survey was to measure connections and engagement on three levels, from the micro to the macro. The foundation survey architects designed a survey that looked first at people’s personal friendships. Then they looked at connections to their neighbours and neighbourhood. Lastly they looked at attitudes toward the larger community of Metro Vancouver.

Clement said the Vancouver Foundation survey answers the question of how connected and engaged we are at all three levels, by examining some of the barriers and some of the consequences. But it doesn’t answer the question of just what it is about Vancouver that makes it breed such loneliness. Clement was quick to point out that completing the survey was only the start of the inquiry.

“Why was this issue [lack of friendships, neighbourhood connections and community engagement] identified as a key issue that was brought up in this community and not in other communities?”

Be My Amigo

Jorge Amigo thinks he is on his way to finding out some answers. Every second week of the month, he runs a small experiment to test his theories. I ended up in his laboratory on a windy Tuesday night in October by making my way down Blood Alley in Gastown and arriving at the door of a cozy tapas bar called Judas Goat Taberna. There, a confident and friendly gentleman about 30 years old with a certain boyish charm greeted me in front of the door. “Hi, I’m Jorge, nice to meet you.” He spoke with an obvious Spanish accent but, from his interactions with others who were beginning to gather, I could tell that he had great command of the English language and was well versed in local slang. He was well dressed but not too formal; he had a form-fitted collared shirt with jeans tight enough to complement his physique but not so tight as to make him seem like a hipster. He had short dark wavy hair, bright eyes, and as expected – from his namesake and burgeoning reputation – he was very smiley and engaging. After about five minutes of hanging out in front he said, “Okay guys let’s move this party inside.” And just like that, Be My Amigo was in session.

After Amigo’s impromptu success organizing the friendly flash mob back in January 2012, the political scientist in him wondered if changing people’s opportunities to interact might shift the culture some in Vancouver. The romantic in Amigo noted that Valentine’s Day was fast approaching. So he organized the city’s first Valentine’s dinner for strangers, which attracted 42 people to the Irish Heather in Gastown. Amigo was pleasantly surprised at how quickly the event sold out. He decided to do more.

“After that, I realized I didn’t want to have the burden of having to organize an actual dinner every other week or have to worry about whether people are paying in advance and making sure they show up.” Amigo decided to streamline the experiment, realizing, “I just need a space where they have long communal tables where people can chat.”

On this night, the space happened to be Judas Goat Taberna. After the original group that gathered in front exchanged pleasantries and small talk, we all headed inside. Before long, the bar was filled with about 30 chatting strangers ordering drinks and food. There was no real structure to what was happening aside from some friendly individuals offering up some amicable conversation, while Amigo was doing his best to greet every newcomer.

I wandered the room asking people where they were from. It seemed like at least half the attendees were native to the Vancouver area and the other half were from abroad. A few of them were born in Vancouver but had spent time away and were now recently back to their hometown trying something new. They came from all walks of life. Most of them were in their twenties and thirties. There were more women than men. Most were single but I met two couples as well. One pair, from the United Kingdom, had just arrived to Vancouver two months earlier and the other, from east Vancouver, was keen on the idea of increasing community connections with a new cast of strangers.

Amigo introduced me to Chris Datta. Thirty-four years old and originally from Vancouver, he had lived abroad for the past 10 years in pretty dynamic international cities. Now he was back in Vancouver trying to expand his social circle. “The thing about Vancouverites is that they are courteous but not friendly,” Datta said. “If you’re lost, they will gladly give you directions but they will rarely introduce you to their friends. Everybody says thanks to the bus driver but nobody will invite you over for dinner.”

Datta told me that this was his third such Be My Amigo event and they kept getting better as he met more interesting people, exchanging numbers and business cards. “These events are great because you show up for two hours, and you meet five or six new people. Some of it’s just chit-chat, some it is lasting friendships.” He wished more Vancouverites were open to this kind of spontaneous interaction with others. He was quick to applaud Amigo for taking the lead to try and break down the perceived social barriers that have been built up in the city. “Jorge Amigo is kind of like the evangelist of talking to strangers in Vancouver.”

Every time I looked for Amigo, he was off chatting up different groups of people in different corners of the room. At one point, I heard him joking with an introverted Asian man in his twenties sitting on his own. “Winston, if you don’t go be social and talk to at least one person, I’m not gonna invite you back.”

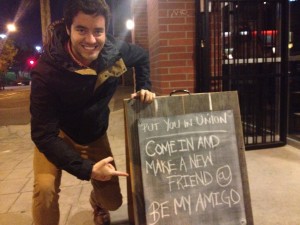

A few weeks later we decided to meet at The Union off Main Street, where, later that night, Amigo would be hosting Be My Amigo 13. It’s hard to imagine Amigo ever being daunted by social challenges presented by genteel Vancouver.

Yet, back in 2007, when Amigo lived on campus at UBC, he was only hanging out with other exchange students. He made a friend from Montreal, who had spent time as an exchange student in Mexico City where she almost immediately felt right at home and had a group of friends. Amigo wasn’t surprised when she told him about her successes on exchange. “I hear from all sorts of foreigners that go to Mexico that they are automatically plugged into society, plugged into a social group. This is something that does not happen in Vancouver. It’s a very impermeable membrane, social groups in Vancouver.”

Amigo leans back in his chair, an obvious expression of satisfaction on his face. He tells me that he is happy with the response thus far, and that now, a dozen Be My Amigo events later, he can conclude two things: A) That social media really works, and B) People are friendly when prompted or others are friendly to them.

“My objective was ‘I want the city to be friendlier, who wants to join me?’ The response has been 100 per cent positive. Calling out for people to be friendly and to be reciprocal with their friendliness simply works.” He also mentioned that there was a certain amount of homogeneity among the type of people who show up. He doesn’t seem to be attracting crazy sports fans or the drunk and rowdy crowd who frequent Granville Street on weekend nights. Rather, the type of people who are open to meeting new people and are curious to meet other strangers. “The people that show up at Be My Amigo are generally not awkward, are not nervous, are not scared of interacting with each other and are not close-minded, which is in direct contrast to what I felt was the problem with the city of Vancouver.”

The urban planning question

Is loneliness built into Vancouver ’s very form? Jorge Amigo suggests that’s the case. When I asked him why, he described a city that, while postcard picturesque, lacked the basic, built-in infrastructure for sociability other cities provide. “Vancouver hasn’t created enough nice squares, like the ones they have in Latin America or Scandinavia or Southern Europe. Here you have Robson Square, which is this shitty plaza with nothing to do and nothing happening there. People get bored after 10 minutes there. There’s a big failure of design where there is no central area in the city where you want to go and meet people.”

What about the seawall? The initial reaction from many who know Vancouver would suggest that it is a great public space that brings people together. When I asked Amigo about it, he sees it as no substitute for a public square, nor does it act like one. Its prime use is rather more of a transition space.

“There’s a lack of adequate communal spaces or interruptions along the seawall to rest or grab a coffee or even a beer. There’s just people running or walking on their own and no organized sociability. You’re not going to stop someone in their path and smile at them and say ‘Hey, you look hot in those yoga pants, let’s sit down and have a chat!” Amigo was also quick to point out that, while he is not a fan of chain restaurants, the new Cactus Club Cafe at English Bay has done a good service building a terrace and concession stand outside. “[The terrace] interrupts the flow of the seawall and you have people that sit there and hang out and look at each other and flirt with each other and all those things promote sociability.

Those sentiments about public spaces were echoed by one of Amigo’s friends, Michael Green of Michael Green Architecture, who joined Amigo when he was invited for his second radio interview, this time on CBC’s The Early Edition, in October 2012. Amigo and Green were there to discuss the unfriendliness label the aforementioned Vancouver Foundation report pinned upon the city and a few of the urban planning woes that led to it. Green sees some of the ultra-dense building in Vancouver as one of the reasons that people are not connecting with their neighbours. “You have all these condos in Yaletown with thousands of tenants yet there is no central meeting area or public space in the building. You can’t even visit your neighbour one floor down without needing a fob to get you in and out of the stairwell.” Yaletown, despite all of its funky cafés, shops and its hip industrial-era facades, comes off as a neighbourhood that is rather aloof.

Maged Senbel, an assistant professor at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning, says the abundance of skyscraper condos like the ones in Yaletown undermine the opportunities to build a community. “When people are so closely packed in, as a first reaction they tend to just protect themselves and put up a bit of a shield.” He says we’ve maximized efficiency of square footage but as a result we don’t have too many spaces that allow for mingling. “There’s no equivalent of the front porch or the common backyard. There are attempts with common rooms and rooftops but they tend to be poorly designed, poorly accessed or insufficient for the number of people in the building.”

Diversity our strength?

According to Statistics Canada, Vancouver is the second-fastest growing city in the province, sixth-fastest in Canada, and owes much of its 9.3-per-cent growth rate over the past half-decade to new immigrants. But the Vancouver Foundation’s report found that a diverse population doesn’t necessarily lead to diverse opportunities for friendships. More than one third polled had no close friends outside of their own ethnic group.

Clement shared this with me as a key finding in her foundation’s report. The study showed that 65 per cent of people surveyed prefer to be with others of the same ethnicity. In private interviews with community leaders – which served as the prequel to the official foundation report over the summer – there were some surprising stories.

Beyond simply being more comfortable in mono-ethnic groups, the interviews revealed that there was some underlying resentment towards certain ethnicities. Clement said that she was shocked at what was confessed, especially the negative refrain about Chinese neighbours.

“People were complaining a lot about their Chinese neighbours. They were upset that they are buying up these big homes, driving up the price of real estate and not living in them, all the while creating a hollowing out of their neighbourhood.” Clement said this was a common complaint from Caucasian neighbours who said the Chinese were changing the look and feel of their community.

Then Clement shared a story that took our conversation about the impact of ethnicity on Vancouver’s friendliness even further. It was about one of her Chinese Ex-co-workers named Tung. He had a father who moved to Vancouver from Hong Kong and would go for morning power walks around his new neighbourhood, largely ignoring the neighbours.

“One morning he returned, threw down his keys and said “I can’t take it anymore!” When Tung asked him what was wrong, his father said all the neighbours keep wanting to say hello to him to which Tung answered, “What’s wrong with that?“ His father replied, “I’m afraid that if I say hello back then they are going to attempt to talk to me, and I’m embarrassed because I can’t speak English.” Clement said when she heard this story a light went on, and she realized it wasn’t arrogance causing insular behaviour. It was fear, or shyness, or a combination of the two. She suddenly she felt more forgiving.

Engaged City Task Force

Too much loneliness can erode the democratic foundations of a city. That’s the view of Vancouver city councillor Andrea Reimer. She says one of the reasons she got into politics was because of a perceived disconnection between the public and public policy and her desire to engage more people in that process. An engaged citizenry leads to electing good people, says Reimer. “Good people make good laws, and if you’ve got not-great people, chances are they’re gonna not make great laws.”

Reimer sensed a problem when she and other city councillors attempted to create a city taskforce to help set guidelines for The Greenest City 2020 campaign and wanted input from the community. She was disappointed at the small number of citizens who were interested in participating.

This past summer, Reimer was in the hospital for a few weeks for a medical procedure and found it interesting what was happening there.

“People who had lots of friends and family around them would be able to go in for surgery and be out the next day. When my medical condition was taken care of, I was out of there an hour later. But for people with low social capacity, there’s not enough human interaction for them to get out of bed to do the walking and the stuff they need to do to be checked off by the medical system.”

Reimer realized this was extra cost for people who are more than healthy enough to go home, but their lack of social networks was keeping them hospitalized. Ironically, the Vancouver Foundation’s report came out while Reimer was in the hospital. She read it on her iPad from her hospital bed.

“Holy mackerel, how did we not ever see this? We put all this money into citizen engagement in city hall, but we’re never going to get there if we can’t increase peoples’ engagement with each other out in the community. That was sort of the big a-ha moment. If people aren’t engaged with their neighbours, they are not going to show up at city hall and engage with us.”

This realization has prompted the city of Vancouver to officially tackle the loneliness issue. Led by Reimer, the city has put together an Engaged City Task Force of 22 people that will devise plans to foster better relationships between citizens and encourage broader participation in local government. Reimer will be requesting a list of quick starts and long-term ideas of what city council can do that would make a big difference, whether that is supporting block parties and opening up streets to pedestrian-friendly environments, or even just putting a bench at a key location.

The task force is looking to target a wide demographic, but specifically it is looking for people between the ages of 25 – 34, which, according to the Vancouver Foundation, is the age group where people are feeling the most isolated. With a shrinking population, Vancouver needs to attract new immigrants. Reimer points out that If that High-productivity group fresh out of college or university can’t find a happy home here because it seems unfriendly to them, then that’s going to have negative impacts.

“From an economic viability standpoint, if the 25- to 34-year-olds are the most disconnected and these are the backbone of the future of the economy – and they are – then we have a serious problem.”

The problem is obviously big enough for the city to justify putting time, energy and resources into selecting this task force. Reimer adds that international competition is a factor and that other cities around the world will be aggressively competing for our fresh-out-of-university talent. She points out that we have lots of positives here but then nonchalantly says, “lack of affordable housing, plus everyone hates me in Vancouver – that’s gonna make it hard to build an economy into the future.”

Once Catherine Clement and her colleagues at the Vancouver Foundation had gathered the data for their report on the problem of disconnection, they attempted a blueprint for improving the situation. “Just by getting neighbours to start to talk with each other,” said Clement, “that in turn can start neighbours doing favours for one another, and thus begins a cascading series of changes. But it all starts with simple conversation… It seems so elementary.”

Clement, for her efforts in co-authoring the Vancouver Foundation’s study, received the good news recently. She will be included in the Mayor’s Engaged City Task Force. In January 2013, Clement and 21 other carefully selected Vancouverites officially began to help Vancouver city hall better connect to the public. Their mandate is to increase neighbourhood engagement, and improve upon the many ways the city connects with Vancouver residents. Their report is due out this June.

Amigo will not be part of the Engaged City Task Force, but he certainly has many ideas of how we can become a friendlier city. When I asked him to share with me three ways, off the top of his head, that we can begin to connect better in Vancouver? He quickly replied with these suggestions:

“First off, the city needs to change the building codes. They need to create some more socializing spaces in and around the buildings. When there’s 2,000 people living in the building and nobody knows each other, that’s a disaster.”

“Secondly, there needs to be a bigger push for public spaces that are liveable, sociable spaces that are inherently nice to be in, where people can enjoy themselves and talk to each other in comfortable surroundings.”

“And the most important thing but also the hardest one is that there needs to be a cultural shift. One that comes from awareness and a realization that it’s much better to be friendly and the reward that comes from reciprocal friendliness.”

Amigo is hoping to see a conglomerate of inspired people setting up events like Be My Amigo that bring the community together consistently in different types of venues for different age groups. “We need [to be] getting people used to the idea that talking to each other and meeting people beyond your friends is healthy and nice and leads to positive outcomes. But the city needs to put a lot of money and effort and support into supporting these community initiatives.”

Even though he wasn’t included in the Engaged City Task Force, it’s as if his prayers for a friendly Vancouver may be answered.

No longer the lone amigo

Two weeks after attending my first Be My Amigo event I went back for another, this one number 14 and held at The Union. Amigo was once again his element. About 40 strangers, or the newly coined “Amigos,” as many have started to call themselves, were hanging out at two of the bar’s long tables. Amigo makes his way in between the tables and addresses the two inside rows whose backs are to each other. He yells out “OK…Everybody on this bench stand up and switch with everybody on that bench.”

About two-thirds of the crowd complies. The others are too engaged in their conversations to bother switching partners.

I see Chris Datta again and we resume a chat about music and bands that are coming to town in the coming weeks. I share with him a story of how Amigo sent me a text ahead of the night’s event saying that it would be “in my best interest to come because about 70 per cent of the people who signed up tonight are female.” Datta smiles and says, “Jorge sent me the same text.” I laugh. Datta laughs. I start to see the power of this movement: Less about bridging the singles gap by creating a welcoming space, but more in meeting great people to connect and reconnect with. I came here looking for a story but along the way it looks like I’ve found a friend here too.

Amigo may have embellished that 70 per cent figure but there were definitely more women than men at the event, a possible reflection of the non-threatening vibe and feeling of safety these events offer. Among them is this twenty-something brunette named Jamie, who is not only attractive but also rather witty. Datta and I spend a good few minutes chatting with her about music, geography, foreign accents and 90s sitcoms. But before Datta and I become too smitten with her, Amigo walks over and gives her a kiss on the cheek. She blushes. He smiles. Before long, it becomes clear to me that this lovely lady is with Amigo. He’s always quite happy, but tonight he seems even more jovial than usual. Now I know why.

Suddenly I reflect back, all the way back, to his Vancouver magazine rebuttal piece called “Do Vancouver women suck?” Somehow I get feeling that if Amigo, 11 months ago, could have seen where he is now, he would have eaten his words then. But I, along with Jamie, Datta, and the 40 new Amigos on this night, as well as the hundreds who’ve experienced Be My Amigo for themselves, are sure glad he went full steam ahead.