I was raised in the Rogue Valley of southern Oregon, in the heart of the Garry oak a.k.a Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) species distribution. My early years were shaped by long afternoons spent wandering sere meadows, chasing lizards and snakes and tossing natural whiffle balls formed by Oregon oak gall wasps (Besbicus mirabilis), and always finding midday reprieve in the shade of mighty oaks. I hadn’t developed my current fascination with trees at that time, but my love for those forests was already engrained in me. If I’d been told then that I would move to another country and study a threatened tree that was considered a weed to farmers around my home, I surely would’ve called shenanigans. Yet here I am, many years later, with a much greater appreciation for the trees that surrounded me, doing just that.

Life amongst the oaks in Totem Field. Trees from high in the mountains of southern California down to the rocky shores of eastern Vancouver Island are planted side-by-side.

Until recently, my study of oaks took me no further than a short walk from my office, where a common garden spanning the species range had been established in 2006 by Colin Huebert, a former MS student of the Aitken lab. It was here that I first began nurturing a fascination with this species. I observed tremendous variation in growth, form, and phenology. Everything from shrubby, hairy, and spindly varieties from California to stout and stately forms from Washington and British Columbia could be found. Sharp-lobed leaves 3cm in length to deeply-sinused and rounded 15cm leaves could be compared on trees adjacent to one another. Although studying the population genetics of this species has been rewarding, I missed seeing these beautiful trees in their natural state.

Over the last couple of weeks I’ve had the pleasure of organising and executing a week of field collections: a whirlwind tour through four populations scattered across southern British Columbia at the absolute margins of the range of Garry oak. Of all the ecosystems to do field work in, rollicking oak meadows –free of the carpet burweed (Soliva sessilis) and poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum) characteristic of the familiar meadows in southern Oregon– must rank among the most hospitable.

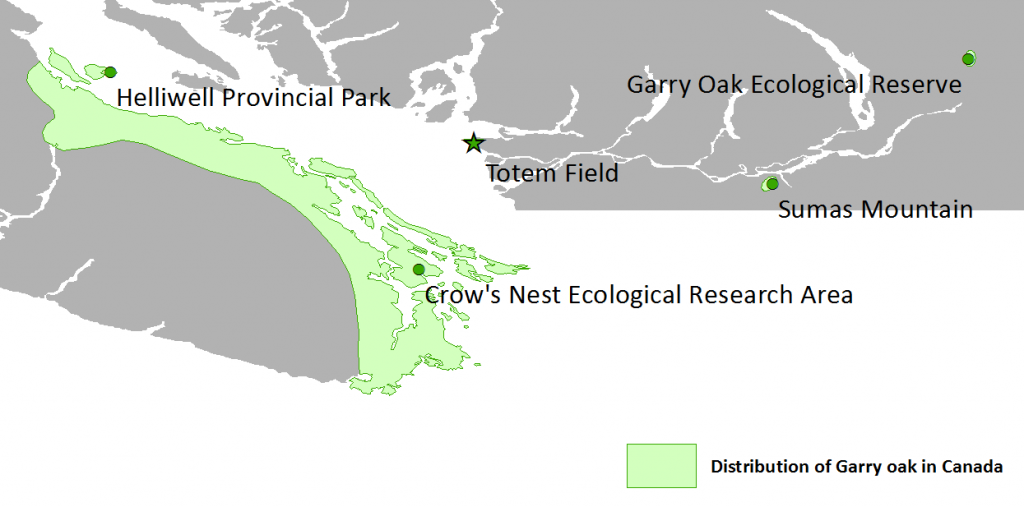

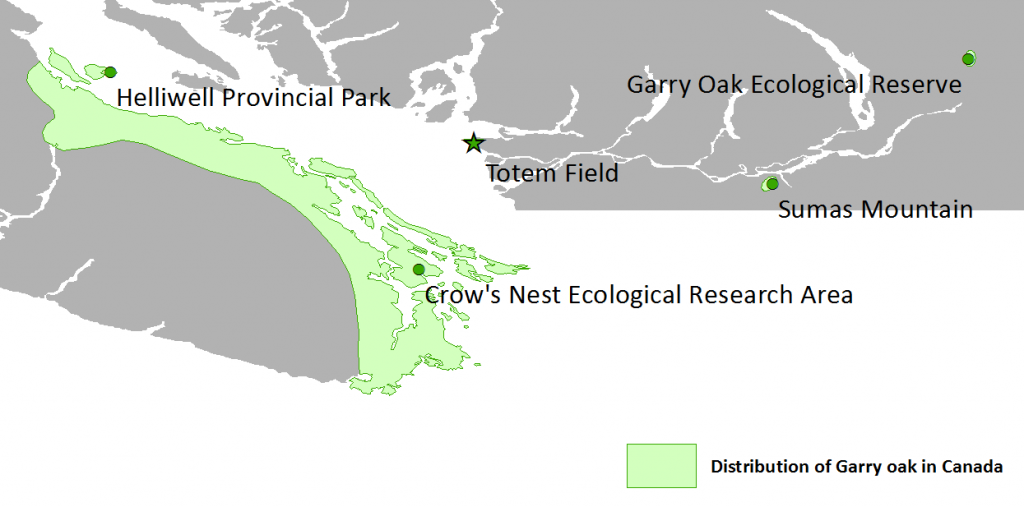

Sampling locations.

Years of living in southern Oregon and the Willamette Valley (where Garry oaks reach their largest sizes) had given me much experience with oak savannahs in the core of the species range. However, my experience at the periphery was very limited. Here, little remains of the once-vast meadows maintained and cultivated by the First Nations. What oaks are left tend to be relegated to craggy bluffs or marginal lands with slightly deeper soils. As with so many dry ecosystems, the spectacular native flora has been largely replaced by exotic grasses and shrubs. Despite all this, the meadows still retain a majestic sense of place and awe upon entry.

I wasn’t sure what to expect from any of these sites as the only one I’d visited beforehand was Sumas Mountain (the location of the oaks there was not well-marked and I wanted to make sure they were worth sampling at all). Bright and early on the morning of 28 April, Sean King and I left Vancouver expecting poor weather and receiving nothing but blue skies and a gentle breeze. Despite how temperamental weather can be at this time of year, we were fortunate enough to hardly face a drop of water that didn’t come from our drinking supply.

Characteristic B.C. Q. garryana meadow. Twin Lichen Meadow, Crow’s Nest Ecological Research Area, Salt Spring Island.

The first stop on our trip was the Crow’s Nest Ecological Research Area on Salt Spring Island. This site was quite literally a walk in the park, complete with a road going most of the way through, with well maintained and signed trails beyond that. It was here we encountered the largest oak on our trip by far (pictured), as well as some staggeringly large Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) veterans. In addition to having the largest oaks, this was perhaps the most expansive of the areas we sampled. We collected samples from trees across five separate meadows and bluffs.

Huggin’ it out with a massive oak in Crow’s Nest’s Spring Meadow.

After a “long, hard day” of sampling, we headed back to Vancouver Island and drove/ferried to our camp site in Fillongley Park on Denman Island. The next morning we hitched a ferry over to the irresistibly-charming Hornby Island, and made our way to Helliwell Park. Dense conifer forests, lush with waist-high salal (Gaultheria shallon) and towering salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis) quickly faded into breathtaking wind-swept bluffs. Bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) were commonplace and we were fortunate enough to catch glimpse of a massive golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos). We sampled a small grove within the park and then headed just outside it to the High Salal Public Trail, where the major grove was located. Although still heavily invaded, this meadow had the most-intact flora of any site we found, with abundant blue camas (Camassia quamash), shortspur seablush (Plectritis congesta), and spring-gold (Lomatium utriculatum). We finished our sampling with plenty of time to hit rush-hour traffic on our way back into Vancouver. Yay!

Gorgeous blue camas (Camassia quamash) in Helliwell Provincial Park, Hornby Island

Sean King with bags upon bags of buds. High Salal Public Trail, Hornby Island

After a day of rest, we were at it again. This time, our goal was to sample two extremely isolated populations in the Fraser Valley, 52 and 128 km from the next-nearest oaks in Bellingham, Washington. The origins of these populations are unknown, although speculation abounds. Hypotheses range from rare dispersals within the crops of mourning doves (Zenaida macroura) or band-tailed pigeons (Patagioenas fasciata), to intentional plantings by First Nations, to the final relics from a broader distribution in times past. Either way they’re certainly oddities and I was very excited to visit them firsthand.

Chocolate lillies (Fritillaria affinis), an unexpected treat to find amongst the oaks of Yale.

Sean admiring the scenic Fraser River from our sampling site in the Garry Oak Ecological Reserve, Yale, B.C.

Once we’d arrived in Yale, we checked in with the local First Nations and were fortunate enough to catch a boat ride out and back from Chief Doug Hansen. Although we hadn’t brought a map of the grove’s location along the river, a short trip upstream revealed some oaks set high on sheer cliffs along the river’s eastern shore. We pulled into a rocky alcove and began scrambling up the boulders and into the forest. The flora at the Yale stand was particularly curious. Plants typically associated with coastal oak meadows such as chocolate lily (Fritillaria affinis) were found side-by-side with interior species like calypso orchid (Calypso bulbosa). The oaks were healthier and more abundant than I’d expected, often sporting a thick coat of mosses and lichens. However, there were many large oaks that had established away from the rocky cliffs and were facing encroachment by Douglas-firs, suggesting that fire may have played a role in establishing and/or maintaining this grove in the past. This site was the most pristine of any of the sites we visited, with only a few patches of exotic grasses. The dense Douglas-fir forest with moss-and-herb floor, air thick and sweet, opening up into oaken glades and cliffs, gave the site a very mystical feel. There is some evidence that this site was once a First Nations burial ground; the uniqueness of the site would certainly lend itself well to sacred purposes.

Peeking out at the Fraser Valley from behind some of the larger oaks at the Sumas Mountain site.

As soon as we were back ashore we set out for Sumas Mountain outside of Chilliwack. As I was familiar with this site, I knew we would be in for some genuine work getting to the trees. The site is some way up a brutally steep slope, with plenty of Himalayan and trailing blackberry (Rubus discolor and R. ursinus, respectively) and stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) along the way. I had the forethought to bring gloves and pants this time around. Despite the scrapes and stings incurred on our way up to the site, the view and the landscape were well worth it.

Large cliffs and boulders overlook the Fraser Valley with some seemingly out-of-place oaks nestled on exposed rock spurs or in sunny patches amongst a matrix of mature Douglas-firs. There are still perhaps fifty mature trees at the site spread atop and below a complex network of sharp granite escarpments, with myriad saplings lining the cliff edges, though the landowners had told me the oaks were more numerous when the farm was established some seventy years ago. Fire scars on some of the veteran conifers and the presence of large oaks among a fairly even cohort of bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum) and Douglas-fir makes me think that this grove may have established after a fire some time ago, with only the largest oaks still remaining amongst the fast-growing conifers and the remainder isolated to the driest and shallowest soils on spurs and cliffs.

Sampling an oak atop an isolated spur on Sumas Mountain.

Once we were back down the mountain and assured ourselves we were free of ticks, we got back on the road just in time for rush hour (again). Drenched in sweat and dirt, we were all smiles as we drove back to Vancouver at a crawling pace.

These outings have given me a wonderful perspective of Garry oak at its most marginal, eking out an existence in the face of human development and encroachment from competing vegetation. At every site, it was apparent that fire probably played a role in maintaining the meadows historically, and their persistence in an era of fire suppression is questionable. Some of the rockiest sites will probably persist for some time, but the deeper-soiled meadows are already shrinking and will certainly continue to do so without human intervention.

The samples I’ve collected on these trips will hopefully provide some insight into genetic diversity and gene flow at the absolute outskirts of the species range of Garry oak, far from other trees. Evidence of high levels of gene flow even at great distance in other areas of the species range suggests that, despite extreme physical isolation, perhaps these populations are staying healthy and viable with help from friends in far-away places.