Oil Exploration in the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge

Viewing the ANWR Drilling Controversy as a Wicked Problem

OIL EXPLORATION IN THE ALASKA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE

By Annie Fang

NOVEMBER 30, 2015

INTRODUCTION

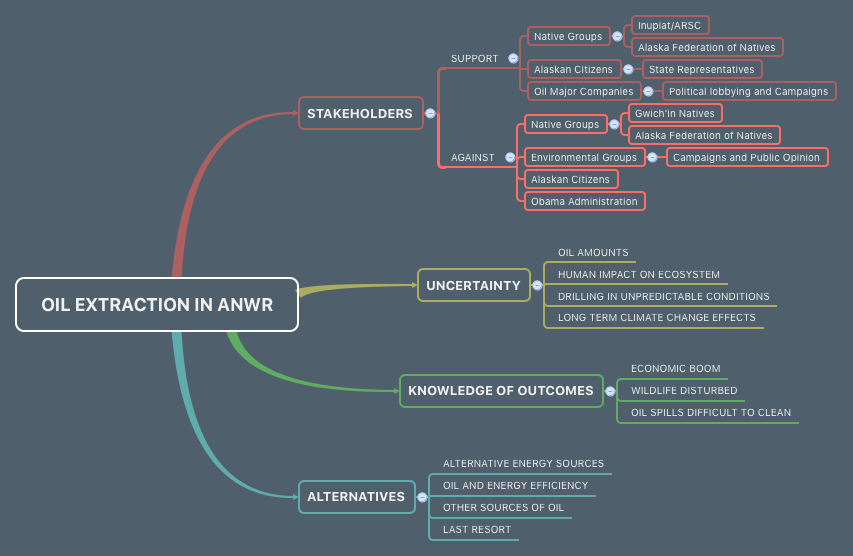

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), is one of the last and largest untouched regions on earth, home to many wildlife species and the largest potential of untapped reserves of oil in the United States. ANWR is located in northeastern Alaska, and was created under the 1980 Alaska National Interests Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) to protect and “conserve animals and plants in their natural diversity, ensure a place for hunting and gathering activities, protect water quality and quantity, and fulfill international wildlife treaty obligations.” (Department of the Interior, 2013) However, uncertainty exists in the amount of oil that can be found within the region since only estimates exist which allude to the ANWR as the greatest source of oil on American soil. Thus, arctic oil exploration has been debated for decades. In this report, I will frame the wicked problem of ANWR drilling by discussing the level of uncertainty and uniqueness involved, the key stakeholders; their interests, and their influence on policy action enacted by the government. Conclusively, I will depict how the current balance of these interest groups by the government is inefficient and further propose a solution that can marry the interests of all stakeholders carrying economic and environmental health interests.

UNIQUE

Resource extraction in ANWR is a unique case, as it is one of the last greatest protected wildernesses in North America. This land is home to a delicate ecosystem and wildlife. It’s borders actually extend into Canada – as drilling would have an effect on wildlife, this could entail international involvement (A. von Hippel, 2015).

UNCERTAINTY

As a wicked problem, oil exploration in ANWR holds great uncertainty. It is difficult to estimate how much oil there is in this region, how humans will impact this delicate ecosystem, and how much the region will change in unpredictable conditions caused by climate change. The tundra, a delicate and slow changing ecosystem, is sensitive to change and human impact, and is “vulnerable to human disturbances due to short growing seasons and slow life processes.” (A. von Hippel, 2015). With current technology, there are no proven sufficient methods of cleaning up oil spills in the arctic (Greenpeace, 2012). Climate change, currently warming the sea ice, creates unpredictable conditions for drilling – which could cause unknown risks for drilling. (Swan and Shearer, 2011)

STAKEHOLDERS

The dilemma that stares on the issue of ANWR drilling is a multi-faceted problem involving the influence of several key stakeholders, each with conflicting interests and agendas. Stakeholders express their distinct interest in the matter of ANWR drilling, exerting influence on government bodies. As a policy maker, the government is perpetually caught up in a balancing act, resulting in a compromise, which ultimately serves no one’s interest.

OIL AND GAS COMPANIES

Oil and gas majors such as Shell; who extract, refine, transport and sell oil, would obviously benefit if they were permitted to extract oil from more reserves. “Shell had viewed the Arctic—one of the few remaining unexplored oil frontiers—as a prize too great to walk away from” (Kent, 2015), as U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management speculated that the Chukchi Sea region could hold the equivalent of 29 billion barrels of oil and gas. Though only speculation, the potential for such vast amounts of untapped oil and gas could bring an unprecedented amount of revenue, given that Shell only had a 6.121 billion barrels of oil and gas reserves in 2014 (Shell, 2014). It is evident that these companies are interested in further oil and gas exploration in the arctic and will as such campaign and lobby for policies that see favorable conditions for such projects to be carried out.

NON-PARTISAN ENVIRONMENTAL GROUPS

Non-Partisan environmental groups such as the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Greenpeace are against drilling in the ANWR. Their belief stands concerned with, not only the direct environment damage of drilling but also with the concern for an oil spill. “The Arctic drilling season is limited to a narrow window of a few months during the summer. In this short period of time, complete the huge logistical response needed to cap a leaking well would be almost impossible” (Greenpeace, 2012). Greenpeace refers to the BP Gulf of Mexico oil spill in stating that, “if BP Oil cannot adequately respond to a spill in temperate conditions near to large population centers and with the best response resources available, how can we be assured by claims that they are prepared to deal with a spill in the extreme Arctic environment?” (Greenpeace 2012). A catastrophic oil spill combined with BP’s poor response, can urge Americans to question the adequacy of oil companies. As Greenpeace continues to speak out against the ANWR drilling, their message has begun to pick up traction following these events. Thus as public opinion begins to move away from supporting oil drilling projects, elected politicians will be required to voice these opinions to appease their constituents.

NATIVE GROUPS

Native groups residing in Alaska are directly impacted by the effects of oil drilling, as a stakeholder their interests are often left unmet. In 1971, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) was established. Motivated by the 1968 Prudhoe Bay oil discovery, the ANCSA act extinguished all Indigenous peoples’ land claims. In exchange, Alaskan Natives were given 5 million of the original 56 million acres of land as well as financial compensation. The Act also created The Arctic Slope Regional Corporation (ASRC) who speaks for the North Slope Inupiat interest. The ASRC supports ANWR drilling and recognizes that many native communities (such as the Inupiat) rely on the oil industry for jobs and tax revenue (Bourne, 2015).“In the form of jobs and tax revenues from the petroleum industry it supports, our land provides the opportunity for economic security, self-determination, and freedom” (Adams, 1995).

As the arctic tundra is a harsh, delicate, and slow changing ecosystem, any change would severely threaten the wildlife. The Gwich’in Indians epitomize a native group opposed to the drilling, reasoning that such devastating change to the ecosystem (that their culture relies on) would ultimately result in an erasure to their cultural identity. Thus, the Gwich’in Indians, opted out of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANSCA), which “extinguished native aboriginal rights to land in Alaska in exchange for a cash settlement of $963 million and a fee title to 44 million acres of land”. (Kristofer, 2002). Although some communities do not support oil exploration as it threatens their way of life, others are supportive having benefitted economically from the oil industry. By looking at political, environmental, and economic influences, we can see that the Native peoples of Alaska’s way of life is both reliant and threatened by the oil drilling.

ALASKAN CITIZENS

As Alaska’s economy is heavily reliant on the oil industry, Alaskans would reasonably support drilling in ANWR. Prodhue Bay Oil Field is the largest source of recoverable oil on American soil, and it is only producing a third of the amount of oil today compared to it’s peak production days. (Bourne, 2015) This huge decline in oil production has a great impact on the economy, which in turn will impact funding for education, infrastructure, and public services. (Arctic Power, 2014) The closing up of ANWR by Obama’s administration has sparked “outrage” in Alaskan citizens and foundations. (Bourne, 2015) This proposal to manage ANWR as a wilderness is working against Alaskan interests and limiting economic growth by closing off “millions of acres of the nation’s richest oil and gas prospects.” (State of Alaska, 2014)

OBAMA ADMINISTRATION

In 2015, Obama’s administration proposed to congress to designate ANWR as a wilderness, to protect it for future generations. This plan of action will involve a revision of the Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CPP) and a completion of an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIS), which will last 15 years (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2015).

On the other hand, it has also been argued that drilling in the arctic would help Americans be less reliant on foreign oil, improve current oil prices, and reduce federal budget deficits. (Lazarri, 2008) Thus, encouraging federal government support.

GOVERNANCE FRAMEWORK

In the case of the allowing oil companies to drill for oil in the ANWR, the issue lies in the hands of the Federal government. However, the issue is influenced by the conflicting interests of corporations and interest groups who in turn influence members of the government, either through constituent representation or other interests. These members of the government will as such voice the opinions of the interest groups they represent in the House of Representatives or Senate when Congress is in session. Thus, as a whole the Federal government is caught up in a perpetual balancing act, ultimately serves no one’s best interest.

| SUPPORT | AGAINST |

| Native Groups: Inupiat/ASRC

→ Alaska Federation of Natives

Alaskan Citizens → Local and State Representatives

Oil Major Companies → Both Federal & State Representatives (Lobbying and Campaigning) |

Native Groups: Gwich’in Indians

→ Alaska Federation of Natives

Non Partisan Environmental Interest Groups: → Public Opinion

|

Native Groups and the Alaska Federation of Natives:

The Alaska federation of Natives is the governing body that makes decisions on behalf of the whole Alaskan Native population. Within this body however, there are representatives from groups such as the Inupiat tribe who support the drilling, and other representatives from groups such as the Gwich’in tribe who are opposed. However, “on June 15th, 1995, by a vote of 19-9, the Board of Directors of the Alaska Federation of Natives passed a resolution in favor of opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for oil and gas exploration” (Chance,1995). Thus, the 1995 decision was unfavorable to the many opposing native voices who may now have experienced the very events they feared would result from drilling.

Alaskan Citizens and Local Representatives:

As discussed earlier, the Alaskan economy is largely dependent on the oil industry and as such their support lies with ANWR drilling. Government representatives are responsible for representing the interests of their constituents. Thus, Alaskan local representatives will voice the support of their constituents, who support the drilling. This can be exemplified through Former Mayor Benjamin P. Nageak, who in a 2003 press release, supported a safe approach to drilling stating that, “ANWR holds resources that can be extracted safely with care and concern for the entire ecosystem it encompasses” (Keepshore, 2003). At a state level, Alaskan Governor Tony Knowles supported “responsible development” in the ANWR as detailed in his March 2001 press release (Knowles, 2001). Knowles also sent “a letter to congressional members outlining his position and is encouraging congressional leaders to Alaska to see ANWR and the drilling technology” (National Centre, 2001). We witness ANWR support move from Alaskan citizens to local representatives and then up to a State representative.

Non-Partisan Environmental Interest Groups:

Many non-partisan environmental groups such as the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) act to regulate, influence and prevent government bodies from introducing policies that will be detrimental to the environment. With respect to the Arctic the WWF claims to, “press governments to fully implement commitments to the Arctic” (World Wildlife Fund, 2015). Environmental groups are not policy or decision makers and only exert influence on governments by swaying opinions of American voters, who will in turn voice these opinions to their government representatives.

Oil Companies:

Similar to Environmental groups, major oil companies can usually only lobby or campaign for favorable political conditions from the government. However as many of these oil companies bring about considerable contributions to the American GDP, government decision-makers sometimes view their interests favorably. History has seen oil companies successfully bribe key government decision makers to create favorable operating conditions. Such bribery can be epitomized by the “Teapot Dome Scandal,” in which Albert Bacon Fall accepted bribes from 2 oil companies in exchange for allowing the oil companies to secretly lease the Teapot Dome (Wyoming) oil reserves (Encyclopædia Britannica ,2015).

MOVING FORWARD

The ANWR oil drilling controversy is a wicked problem with no clear solution. There several alternatives or courses of action that can be taken. However, even these solutions present some degree of uncertainty. The first option relates to encouraging the development of renewable alternative energy sources through government programs. The second proposition includes improving energy efficiency in production. Other solutions include pursuing other sources of oil and using ANWR oil as a “Last Resort”.

ALTERNATIVE ENERGY SOURCES

Renewable energies in particular are a viable alternative to oil production, and can reduce the increase in climate emissions. Reducing CO2 emissions is not enough – there also needs to be legislative change as well as technological innovation, as well as economic incentive for investment in alternative sources in of energy. Renewable energies, like wind, solar, and hydro, are technologies that already exist today. However, in the U.S., most of these types of energies remain economically unattractive due to production costs, lack of short-term economic gain, or not being readily and consistently accessible (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2015). These technological innovations produce long-term economic gains, but are less attractive due to the significant start up capital (FSFCCCSWF, 2015).

As oil reserves are running dry, it is becoming apparent that a shift towards renewable energy is necessary. Government bodies can encourage the growth of renewable energy through incentivized rebate programs or grants that mitigate the risk of significant start up capital. No longer can our economic system be concerned with short term gains, as such a system is doomed to inevitably fail.

The shift towards renewable energy sources has increased globally, with an increase in solar and wind energy investments in 2014 (Frankfurt School FS-UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance, 2015). With government programs that encourage renewable energy alternatives, both economic interests and environmental health interests can be satisfied. Corporations and individuals seeking to maximize profits will consider renewable energy alternatives as a profitable opportunity, while environmental interest groups can feel confident on the health of the environment.

OIL AND ENERGY EFFICIENCY

There is a large amount of energy wasted on inefficient production methods. Government bodies should incentivize individuals and corporations to not only conserve energy, but also improve energy efficiency. Globally, an “increasing number of countries has adopted targets and policies to improve the efficiency of buildings, appliances, transport vehicles, and industry.” (Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century, 2015). This solution can slow down the inevitability of tapped oil reserves, but cannot act as a stand-alone solution. The most effective solution would combine the development of renewable energy sources with an effort to increase oil and energy efficiency.

OTHER SOURCES OF OIL

Being the top oil consuming country in the world, the U.S. does not produce enough oil to sustain its oil use – most oil consumed in the U.S. is foreign (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2014). Although imported oil drives up oil costs, drilling and oil exploration in ANWR’s harsh tundra environment is also costly. In 2015, Shell abandoned the arctic after spending billions on oil exploration. This implies that the logistical costs of retrieving the oil given current technology were great enough to be deemed economically not worth pursuing. Many countries, including the U.S., must search deeper underground, or further out into remote and harsh environments, or drill offshore to find oil. Estimates show that the majority of oil is actually found offshore, underwater. (Bourne, 2015) Alternatives of drilling in ANWR would simply include pursuing oil elsewhere – mainly offshore or foreign oil. In particular, areas which present easier access to obtaining oil and less challenges in the event of an oil spill could pose as more attractive sources than the ANWR.

LAST RESORT

Currently, Shell and other oil companies have withdrawn from oil exploration in the arctic, but these arctic oil explorations are far from being forgotten. Oil reserves in ANWR could possibly used as a “Last Resort.” Currently, it is very costly and risky to drill in this type of environment. However, if technological advancements and new strategies were implemented to reduce the cost and risk of drilling, then ANWR would become an economically viable prospect once again.

WORKS CITED

Peer Reviewed Articles

Lazzari, S. (2008). Possible federal revenue from oil development of ANWR and nearby areas.

(pp. 9p-9p)

Pasquale, K. (2002). ANWR: The legislative quagmire surrounding stakeholder control and

protection, and the practical consequences of allowing exploration. Buffalo Environmental Law Journal, 9(2), 245.

Government Documentation

Adams, J. (1995). The Office of the President. Retrieved from

http://arcticcircle.uconn.edu/ANWR/asrcadams.html

Chance, N. (1995). Alaska Federation of Natives. Retrieved from

http://arcticcircle.uconn.edu/ANWR/anwrafn.html

Department of the Interior. (2013) About The Refuge. Retrieved from

http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Arctic/about.html

Knowles, T. (2001). Press Release. Retrieved from http://www.gov.state.ak.us/press/01082.html

State of Alaska. (2014). Obama, Jewell Attacking Alaska’s Future. Retrieved from

http://gov.alaska.gov/Walker/press-room/full-press-release.html?pr=7063

U.S. Department of the Interior. (2015). Obama Administration Moves to Protect Arctic National

Wildlife: Recommends Largest Ever Wilderness Designation to Protect Pristine Habitat. Retrieved from https://www.doi.gov/news/pressreleases/obama-administration-moves-to-protect-arctic-national-wildlife-refuge

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2015). Retrieved From

http://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/index.cfm?page=renewable_home

Popular Media

- von Hippel, Frank. (2015). Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Retrieved from

http://www.pollutionissues.com/A-Bo/Arctic-National-Wildlife-Refuge.html

Bourne, Joel K. Jr. (2015, Feb 5). What Obama’s Drilling Bans Mean For Alaska and the Arctic.

National Geographic. Retrieved from:

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2015/02/150205-obama-alaska-oil-anwr-arctic-offshore-drilling/

Encyclopædia Britannica. (2015). Teapot Dome Scandal. Retrieved from

http://www.britannica.com/event/Teapot-Dome-Scandal

Keepshore, P. (2003, February). Inupiat Eskimos First Best Environmentalists. [Web log

message] Retrieved from http://www.freedomwriter.com/issue25/ak7.htm

Kent, S. (2015, September 28). Shell to Cease Oil Exploration in Alaskan Arctic After

Disappointing Drilling Season. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://www.wsj.com/

Snow, Nick. (2015) Obama administration proposes making ANWR Coastal Plain wilderness.

Retrieved from http://www.ogj.com/articles/2015/01/obama-administration-proposes-making-anwr-coastal-plain-wilderness.html

Swan, C., and Shearer, C. (2011, October 7). Drilling in the Arctic: Perspectives From an

Alaska Native. [Web log Message]. Retrieved from http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2011/10/07/338726/drilling-in-the-arctic-perspectives-from-an-alaska-native/

Grey Literature

Arctic Power. (2014). Local Governments Support Opening ANWR. Retrieved from

http://anwr.org/2014/11/local-governments-support-opening-anwr/

Frankfurt School FS-UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance.

(2015). Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2015. Germany: Author.

Greenpeace. (2012). The Dangers of Arctic Oil. Retrieved from

http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/campaigns/climate-change/arctic-impacts/The-dangers-of-Arctic-oil/

Randall, T. (2001). Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Drilling Debate Steps Up. Retrieved from

https://www.nationalcenter.org/TSR52201.html

Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century. (2015). Renewables 2015 Global Status

Report. Paris, France: Author.

World Wildlife Fund. (2015). Our Solutions. Retrieved from

http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/where_we_work/arctic/what_we_do/

Data Sources

Shell. (2014). Proved oil and gas reserves. Retrieved from

http://reports.shell.com/investors-handbook/2014/upstream-data/proved-oil-and-gas-reserves.html

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2014). Petroleum Statistics. Retrieved from

http://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/index.cfm?page=oil_home#tab3