Commodity Chain

EAST VAN ROASTERS CHOCOLATE COMMODITY CHAIN ANALYSIS

a commodity chain analysis by Annie Fang

INTRODUCTION

For my project, I was interested in researching the production processes of cocoa in chocolate bars. Recently, I came across a local café called East Van Roasters, which produces their chocolate bars and drinks straight from the cocoa bean by hand. This “Bean to Bar” process (East Van Roasters), which could be watched from the outside and inside from your table at the café, was intriguing to me because the entire café consisted of both the place of production and the place of consumption of the chocolate bar. Inside the café, I was able to choose from a variety of chocolate bars, with their flavors labelled as the countries their cocoa beans originated from. Choosing a chocolate felt like a mini tour of Latin America, where I could “explore” cocoa flavors from Puerto Rico, Madagascar, and Peru. Settling on the “Dominican Republic” chocolate bar, I took my seat, and took in my surroundings. The interior decorating was natural and organic looking, which went well with the packaging of the chocolate I had just purchased. With a quick look at East Van Roaster’s website, I learned that the company was supporting several environmental and social humanitarian issues, many of which I was personally previously interested in. The Even the ingredient label, which read “Organic cocoa beans, Organic cane sugar, Organic butter”, made the experience more special and appealing to me, as the consumer.

Upon further research into the actual production process of Dominican Republic cocoa, I discovered that the cocoa was produced by a company that also supported environmental and social humanitarian issues. This emphasis on these social issues creates symbolic value, in addition to the physical value of the chocolate. The marketing of this product, which creates the symbolic value, is determined by individual and collective identities and relationships of consumers.

By studying the social and spatial relationships created during the production of Dominican Republic cocoa, we can see that through consumption and production of self identity creates the value of cocoa, which have several advantages and disadvantages for the lives of cocoa farmers in the Dominican Republic.

ORIGIN: Dominican Republic Cocoa Beans

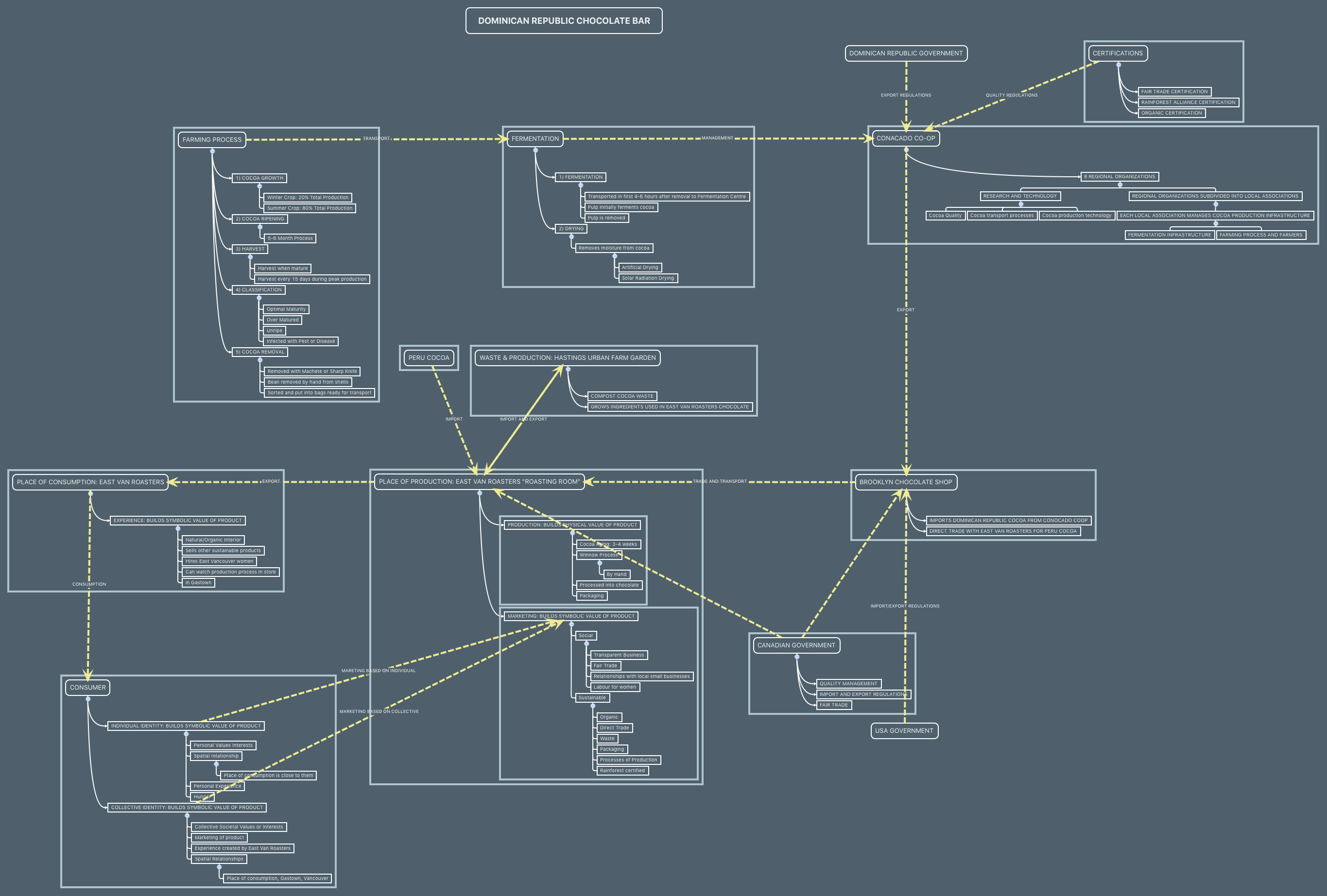

This commodity chain graph depicts the distribution networks of cocoa from the farmer in the Dominican Republic all the way to the consumer. It outlines the key players and processes that lead to the final product, as well as outlining key details on what produces the symbolic and physical value of the product. To view this diagram in detail, I have provided a link where this can be viewed online: http://goo.gl/n8ekrV

During my research of the cocoa production process, I called the store to speak with the store manager of East Van Roasters to ask about their source of Dominican Republic cocoa beans. Unlike most chocolate bars, the place of consumption (the store) is the same as the place of production for their Dominican Republic chocolate bars, so I was able to focus on transportation and import questions of the cocoa. During my interview, the manager explained that they imported fair trade cocoa beans from Peru, and actually directly traded bags of Peruvian cocoa beans for Dominican Republic Cocoa beans with another chocolatier shop in Brooklyn, New York, USA. From there, the Brooklyn chocolate shop imports all of their cocoa from Conacado Co-op (Bolton, per. com.).

Conacado Co-op is an organization in the Dominican Republic that focuses on fair trade for cocoa farmers in the country. It manages 8 regions, with each region managing local production and creating infrastructure for farming and fermentation processes (Cocoa). With this organized collaborative effort, this organization is able to provide better income for farmers by economic and political processes of influencing the international market value of cocoa (Conacado-Commerce). They also improve the quality and value of cocoa by meeting higher quality standards and certifications, by improving production infrastructure. Some of these standards include the Fair Trade certification, Organic certification, and Rainforest Alliance certification. This emphasis on quality throughout the production processes and the overall management of cocoa farms has improved the lives of Cocoa Farmers in the Dominican Republic.

THE VALUE AND MEANING OF COCOA

“Social relations give the commodity value, not it’s actual use or qualities.” (Sundberg 2015)

Commodity chains represent the relationships of the individuals who engage with it. Through consumption, we are building a network of people around the world. Commodities are no longer produced at the point of consumption – in this case, first-world nations – they are often produced in developing countries. As a result, a first-world consumer can purchase a commodity or experience, and develop a social and spatial relationship with the producer, or farmer. These relationships tear down international boundaries, creating a globalization effect. As a consumer, I am able to “experience” a minuscule part of another culture without leaving my neighborhood. For example, by simply walking through a grocery store, I can fill my cart with organic bananas from Costa Rica, chocolate from Madagascar, and Acai from Brazil. I am connecting myself to a farmer or culture of the commodity’s origin.

In my commodity chain graph [5], each key player has an important role in producing the physical and symbolic value of the product. Physical value represents the material value, which is produced by processes that physically create the final product. This would entail the increase in economic value in cocoa by looking at the quality, compared to other cocoa in global markets. Conacado Co-op has a key role in the actual production and quality control of cocoa, as well as influencing global markets. The farmers themselves influence economic value, as they are responsible for producing higher quality cocoa. Towards the end of the commodity chain, at it’s production level, the “Roasting Room” (Bolton, per. com.) would be responsible for ensuring that their cocoa beans were processed properly, and good for consumption.

Symbolic value is produced by processes of the production individual and collective identities. “Production produces more than just commodities; individual and collective identities are constituted in the process of production” (Ramamurthy 1995: 741) We build our identities through consumption, by purchasing products or experiences we place value on. “These values are dependent on the individual, but are also driven by ideals produced by collective culture and marketing through forms of media.” [7] This can be exemplified by my choice to buy chocolate from East Van Roasters. This chocolate and business represents sustainable values and social values that I, as a consumer, believe in, and by consuming it, I am using it as a means to represent my own identity. The values I choose to place importance on are in turn highly influenced by my collective identity, which contributes to and its produced by marketing during the production of the chocolate.

The marketing of East Van Roasters chocolate in particular emphasizes sustainable and social values, which add symbolic value to the product. T East Van Roaster’s website states, “Working with philanthropic suppliers is very important to us. Direct trade is ideal because it means that the farmers are getting more for their product. Organic means that the farmers are working in a healthier environment and fairly traded is great if it doesn’t prove too costly for the farmer” (East Van Roasters) The importance on “organic” is marketed through media, through it’s packaging, and through appearance of the store itself. This gives a strong impression on consumers who value these types of ideals. The chocolate itself is produced by hand, which can be observed within the store. This attracts customers who valued supporting local businesses. During my conversation with the store manager, she emphasized that all their products encouraged “fair trade” and “directly traded” products. The promotion of being able to help farmers, as well as labelling of countries of origin (For example: Dominican Republic, Peru, and Madagascar) gives the consumer a feeling of connectedness to the farmer.

Symbolic value of commodities is largely built by marketing and media. For example, by examining the production of Madras shirts (Ramamurthy 1995: 741), the advertising is misguiding the consumer by telling an incomplete and incorrect story of it’s production. This version is catered to the consumer’s values, and not the producer’s. As a result, the consumer will only know what is advertised, which is an incomplete perception of the people and culture that made the commodity. “We cannot see the fingerprints of exploitation upon them or tell immediately what part of the world they came from.” (Sundberg 2015) As a result, what we imagine the product to be is a construct of capitalism.

Labelling the chocolate with country names as flavors is problematic. Although initially I may feel like I am creating a relationship with the farmer, or the place of origin, my continued consumption of the “symbolically” valued product emphasizes my relationship with it, as well as it’s place of consumption. My relationship is built on my own habits and interests, and I begin thinking of the experience I have when I consume the chocolate in East Van Roasters. As a result, by consuming this product, I had eliminated the connection I had with the producer, and put more importance on the symbolic value generated from this relationship I had cultivated with this commodity. When I think about the Dominican Republic, I have realized I do not know much – I have only come to know it as a flavor, symbolic of another culture. Thus, we are eliminating the social and spatial networks cultivated by commodity chains.

As a result, we disconnect ourselves, the consumer, from the producer. “Banana Split”, a short documentary on Banana commodity chains, interviews a series of grocery shoppers. Bananas are always readily available and popular fruit in Canada, but when asked if they knew about where or how they were grown, most were unsure (Saxberg 2010). Although I was initially aware of the origin of Dominican Republic chocolate, marketing skews and misrepresents the countries it comes from. The marketing only emphasizes what we, the consumer, place value on the product itself.

Therefore, the responsibility of generating awareness of issues like “fair trade” falls onto the consumer, through research. Consumers often buy into products simply because they are labelled to be “organic” or “fairly traded” without a full understanding of what these labels really mean. The story of the Madras cloth producer and his life exemplifies this. He is depicted as a hardworking man, while his wife, is unnamed, and her work is not recognized by the article. Men are often seen as the heads of the household, the breadwinners, and women do unpaid housework. And yet, the advertising of the Madras shirt makes it appear as though the consumer of the product would be helping the farmer. (Ramamurthy 1995: 741)

It is only with my own research, that I was able to learn about issues of fair trade for farmers in the Dominican Republic – but this is not the case for the typical consumer. Although it is generally beneficial to farmers for a company like East Van Roasters to promote these types of environmental and social issues through their product and marketing, it is still a small company and incredibly unique compared to the majority of chocolate manufacturers around the world. Even when these issues are promoted, the initial meaning can be lost as the consumer develops this intriguing relationship with the product. Arguably, perhaps some awareness, even through advertising processes and the skewing of information, is better than nothing. However, this economically biased emphasis on specific information about products can still continue to marginalize farmers. Through marketing, the lives of the farmers themselves become “invisible”.

WORKS CITED

Artisan Chocolate + Coffee. Web. 18 Nov. 2015. <http://eastvanroasters.com>.

Bolton, Shelley. Personal Communication. East Van Roasters Store Manager. 13 Nov. 2015.

“Conacado-Commerce équitable en Rép Dominicaine – Cacao.” Ethiquable. Web. 18 Nov. 2015. <http://www.ethiquable.coop/fiche-producteur/conacado-commerce-equitable-rep-dominicaine-cacao>.

“Cocoa Process.” Conacado Agroindustrial. Web. 16 Nov. 2015.

<http://www.conacado.com.do/?page_id=39&lang=en>.

East Van Roasters. Advertisement. “Cacao + Cane Sugar.” 20 April. 2015. Web. 18 Nov. 2015.

Fang, Annie. “East Van Roaster’s Dominican Republic Chocolate Bar: Cacao.” UBC blogs. 16 Dec. 2015. Web. 16 Dec. 2015.

Fang, Annie. “The Marginalization of Women in Commodity Chains.” Geo. 395. Assignment 2.

U of British Columbia. Nov 21 2015. Class Assignment.

Ramamurthy, Priti. “Why is Buying a “Madras” Cotton Shirt a Political Act? A Feminist

Commodity Chain Analysis.” Land’s End Catalog (1995): 734-766.

Saxberg, Kelly. 2010. Banana Split. https://vimeo.com/17275072

Sundberg, Juanita. “Commodity Fetishism and Commodity Chains.” Geog. 395. U of British

Columbia. 10 Nov 2015. Class Notes.