- In The Truth about Stories, King tells us two creation stories; one about how Charm falls from the sky pregnant with twins and creates the world out of a bit of mud with the help of all the water animals, and another about God creating heaven and earth with his words, and then Adam and Eve and the Garden. King provides us with a neat analysis of how each story reflects a distinct worldview. “The Earth Diver” story reflects a world created through collaboration, the “Genesis” story reflects a world created through a single will and an imposed hierarchical order of things: God, man, animals, plants. The differences all seem to come down to co-operation or competition — a nice clean-cut satisfying dichotomy. However, a choice must be made: you can only believe ONE of the stories is the true story of creation – right? That’s the thing about creation stories; only one can be sacred and the others are just stories. Strangely, this analysis reflects the kind of binary thinking that Chamberlin, and so many others, including King himself, would caution us to stop and examine. So, why does King create dichotomies for us to examine these two creation stories? Why does he emphasize the believability of one story over the other — as he says, he purposefully tells us the “Genesis” story with an authoritative voice, and “The Earth Diver” story with a storyteller’s voice. Why does King give us this analysis that depends on pairing up oppositions into a tidy row of dichotomies? What is he trying to show us?

———————————————————————————————–

In telling the “Earth Diver” and “Genesis” creation stories, King uses dichotomy in a multitude of ways to highlight the methods through which the stories we believe and embrace are essentially our own choice. In presenting the stories as a dichotomy, King reminds us that “you have to be careful with the stories you tell and you have to watch out for the stories that you are told”; by presenting the stories as incompatible and contrasting, King actually challenges the reader or listener to consider if this dichotomy is necessary, and if so, how we have been conditioned to accept one story as sacred and the other as secular. King acknowledges that he spends more time focusing on the Earth Diver story, largely because the majority of the audience is not working from a place of existing knowledge of this creation story. However, in approaching it this way, King also draws the audience’s attention to the fact that they do know the story of Genesis. Regardless of their own religious beliefs, King makes the audience question how the Genesis story became so pervasively known within our culture. Without directly asking the audience this question, King demonstrates an alternative by choosing to examine the Earth Diver story more thoroughly. King chooses which story to privilege, modeling his argument regarding how the dichotomous representation of the stories necessitates declaring one as sacred and one as secular. As King writes, “we are suspicious of complexities, distrustful of contradictions, fearful of enigmas.” Dichotomies are easy. Choosing is easy. Challenging the dichotomy is hard, and changing your mind is even harder.

By using an authoritative voice when describing the Genesis story, King highlights how prominent this narrative is in Western culture. He can shorten the story because most of his audience already knows it. He can explain the story from an assumption of the audience’s knowledge. Comparatively, when King tells the Earth Diver story, he crafts it cooperatively and collaboratively. King can assume the audience is coming from a shared place of not-knowing. Just as King challenges the way the Christian Genesis narrative creates a sense of hierarchy by crafting God, then the world, then animals, then man, and finally woman, he challenges the hierarchy with which Christianity asserts its authority by presenting the collaborative Earth Diver creation story from a place of assumed equality. Telling the Genesis story by assuming others know it already creates a hierarchy between “knowers” and “non-knowers,” Christians and non-christians, members and non-members, in-group and outgroup. Telling the Earth Diver story in completeness, with humour and questions to the audience, makes the storytelling process collaborative and functions by assuming the audience is coming from a place of sameness: of not knowing, but being curious, much like the tenacious curiosity of Charm in the story. He creates togetherness. King also makes this storytelling process a bonding experience; unlike the often punitive doctrine of Christianity, Native storytelling is meant to involve laughter, joking, and flaws. Listening to the story and laughing together is part of the experience.

Much like King, I don’t wish to imply that a punitive and isolating experience of Christianity is the only way of engaging with that religion and its stories. There are many Christians who embrace messages of openness, acceptance, tolerance, generosity, and kindness, and whose experiences with religion have involved community, curiosity, and the creation of a social network. Many Indigenous people in Canada also identify as Christian and see benefit, importance, and significance in doing so. However, I think it is arguable that in the larger picture of colonialism, and particularly in how Christianity was brought to Canada, fear and autocracy has been a prominent feature in Christianity’s spread, particularly within the First Nations communities of which King speaks. He is using dichotomy to show us the ways a dominant narrative eradicates or diminishes the value of alternatives. He is challenging us to consider our own agency in the stories we interact with, put faith in, tell to others, and have told to us. I believe this strategy is an attempt to get the audience to consider when and how they came to know the Genesis story instead of the Earth Diver, and how complicit, complacent, or agent they are in assigning one more importance than the other. When King says, “Take Charm’s story, for instance. It’s yours. Do with it what you will. Tell it to friends. Turn it into a television movie. Forget it. But don’t say in the years to come that you would have lived your life differently if only you had heard this story,” he is giving the audience the option to change their relationship to the world and to take agency in their decisions. It is not good enough to say you would have done differently if you had only known of the alternatives: he has presented the alternatives, and the choice is now left in the hands of the audience.

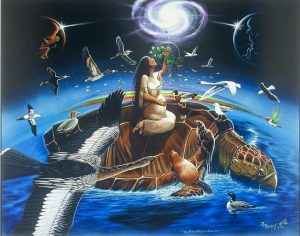

Thomas, J.B. The Birth Story of Creation. 2001, oil painting on canvas. Accessed from www.takentheseries.com/the-great-beginning-of-turtle-island/

Works Cited

Belshaw, John Douglas. “4.7: Canada and Catholicism.” Canadian History: Pre-Confederation, opentextbc.ca/preconfederation/chapter/4-7-canada-and-catholicism/. Accessed 7 Feb 2019.

Marley, Karin. “Majority of indigenous Canadians remain Christians despite residential schools.” The Current, CBC, 1 April 2016, www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/the-current-for-april-1-2016-1.3516122/majority-of-indigenous-canadians-remain-christians-despite-residential-schools-1.3516132. Accessed 7 Feb 2019.

“The Role of the Churches.” Stolen Lives: The Indigenous Peoples of Canada and the Indian Residential Schools, Facing History and Ourselves, www.facinghistory.org/stolen-lives-indigenous-peoples-canada-and-indian-residential-schools/chapter-3/role-churches. Accessed 7 Feb 2019.

Ziervogel, Katarina. “The Birth Story of Creation by JB Thomas.“ 2001, oil painting on canvas. The Beginning of Turtle Island, TAKEN The Series, 6 July 2018, www.takentheseries.com/the-great-beginning-of-turtle-island/.

Hi Charlotte!

Thank you for your post! I came to a lot of similar conclusions that you did, although I think you put it all together a little more eloquently…Anyway, as I was reading you reminded of a thought I had while reading the last line of that chapter, the “Take Charm’s story, for instance. It’s yours. Do with it what you will. Tell it to friends. Turn it into a television movie. Forget it. But don’t say in the years to come that you would have lived your life differently if only you had heard this story” line. Do you think that King is trying to persuade us, or to make us believe that the Earth Diver story is “better” for lack of a better word than the “genesis” story? This last line of his confused me. As it was my impression the whole chapter was him arguing for a more open and joined view of the world, and yet with this last line it seems he’s arguing the world would be a better place if we had had the “earth diver” story from the beginning rather than “genesis”. I’m not saying either of those views is right or wrong, but was wondering if you noticed this possible contradiction as well?

Hi Ross,

I definitely did find this conclusion potentially contradictory. Much of his discussion in the lecture is in opposition to a binary or dichotomous approach to the world, so this concluding statement was one of the sections I found most thought-provoking. While I think King can be seen as asking the reader to “make a choice,” I think the broader purpose of this is a little more ambiguous. While I don’t necessarily think King is saying the Earth Diver story is superior, I think he is challenging the audience to consider the values ingrained in both retellings, and how the importance of these values may shape the way they currently engage with the world. In this sense, King’s discussion of Christian tellings of Genesis could be seen as King presenting the argument that because the Christian Genesis story is so prominent, few people have taken the chance to really consider how it shapes their lives and whether their knowledge of it was a conscious choice. Then, in presenting the Earth Diver as an alternative, he’s forcing the listeners to not be able to rely on the idea of not knowing of any alternative as an explanation for their choices or behaviors; he has presented the alternative Earth Diver approach and has shared that knowledge. It is up to the audience to decide how to use it.

I enjoyed reading your post- I found it to be very eloquent, as Ross mentions! Your discussion of the authoritative aspect of Christianity (Christianity has indeed been, traditionally, an authoritative religion- after all, for many years, the Bible and its stories were largely inaccessible for the common person!), as well as mentioning its prominence had me thinking. For a long time, most Westerners would consider the Genesis story to be the “sacred” one and the story of charm to be “secular”. However, as today’s generation moves farther away from organized religion (arguably with stronger faith in science), I wonder which story would be more favorable. I feel that younger generations are more likely to resist Genesis with its authoritative tone, and more likely to embrace Earth Diver- not as fact, but as metaphor. Science would reject both of these stories as factually untrue. Yet, as interest in organized religion wanes, I think there is more room in our world for a story like Charm’s- one that promotes equality and collaboration, ideas that are more sacred to most people today than the idea of order and hierarchy.

Hi Marianne,

I think the discussion you’ve brought up about science’s role in our understanding of the creation of the universe is really fascinating. It’s definitely true that at least in our area of the world, religiosity has faded in its role in education, politics, etc. This has me wondering about the value of stories within the context of a more scientifically-invested culture. To address your comment on whether the creation stories still hold value given this scientific context, I think the point you made about metaphor is really interesting–while science may be able to give us factual evidence and explanations of the world, it is sometimes less able to help us interpret the intangible elements of the human experience. While we may understand the big bang, for example, it does not address ideas of our individual or broader purpose in the way a metaphor or creation story does. I think there is a deeply human need to be able to understand ourselves within a broader context, and for that, we need stories to help us communicate our own narrative. Stories give us an understanding of connection, of meaning, and of values that help us feel grounded in the world. More broadly, I think it’s also arguable that for many, science serves the same role of explaining our place in the world and how we “came to be,” and I do not think there is a dichotomy between a scientific and a religious approach–both are ways of interpreting our existence.

Hi Charlotte,

Thank you for this well-reasoned and insightful post! I am now kicking myself for falling right into the dichotomy trap of also holding the stories of Genesis and Charm as a binary opposition, whereas, as you very astutely point out, there are a number of Indigenous Canadians who are also Christian. It is interesting that King himself doesn’t seem to tease out this seeming contradiction, as Ross has pointed out here – although his writing is rife with playful, tongue-in-cheek reversals and moments of sly sarcasm, so it’s possible King is trying to lure his reader into the conversation and into making informed conclusions autonomously, rather than being similarly swayed by the hegemony of King’s own telling.

I most confess that I am not particularly well-acquainted with contemporary intersections between Indigenous culture and historicity and Christianity, but it’d be really interesting seeing how generations of Indigenous people could have melded together the two strains of Creation myths (although, having posited that, I’m immediately worried that the Eurocentric Christian telling would overwhelm the Indigenous spiritual presence, as was tragically the case with most other such moments of cultural intersection). Do you think that King’s contrasting of the two stories is meant to be part of (as you very well articulate) the conversational ‘bonding process’ of Indigenous storytelling – promoting a conversation and confluence of different views? Perhaps King, in trying to air out the contrasting spiritual backgrounds in a contemporary context, is attempting to lay the foundation for future such conversations between different spiritual backgrounds, and how the similarities and differences could help elucidate respective belief systems? Your take on King seems to echo mine, in reading him as a touch more optimistic than dogmatic – what do you think? Thanks again for a great read!

Hi Kevin,

Thank you for your thoughts and questions! I would also say that I am not well-versed on modern indigenous relationships to Christianity, but would certainly be interested in seeing more examples of people who have chosen to embrace multiple belief systems and this could be an excellent way of exemplifying the point King makes about rejecting binaries and false dichotomies, and to see how this is reclaimed or responded to given the context of residential schools and our typically Eurocentric view. I don’t want to speak too much on my thoughts in this area/assumptions, just because I certainly do not have Indigenous lived experience and want to avoid inserting my own potentially inaccurate views here.

However, I will comment on your questions about the purpose of offering contrasting views in the structure that King uses to create his argument. I agree with the idea that it is not merely what King says, but how he formulates it that is important; the lecture format of the original broadcast involves multiple levels of communication as both a live talk, a radio broadcast, and as a published written work, and King seems to take this into consideration with his storytelling. He is explicit regarding his choice to spend more time on Indigenous narratives, and explains the purpose behind doing so: we have already been exposed to the Christian version enough that it is ingrained in our cultural memory and understanding. I think King uses a collaborative approach to help the audience invest in the Earth Diver story, and uses a storytelling approach knowing that many readers/listeners may already hold beliefs about the “authenticity” or “authority” of the Christian Genesis story; by presenting the Earth Diver perspective as a storyteller, King allows an audience of diverse backgrounds to consider the story without dogmatizing it. He is not explicitly telling them what to believe or why their narrative is wrong, he is showing them an open and curiosity-based way of learning about other cultures. In that sense, I would say it’s certainly not unreasonable to think that King is presenting a way to open up a dialogue between multiple belief systems, and in doing so, to challenge the readers/listeners to consider what factors made them invested in their own beliefs, and if this was an intentional decision on their own part, or one made because of dominant narratives within our culture as a whole.

I definitely agree with your point about King being more optimistic than dogmatic. He seems to challenge the dogmatic interpretations of Christian belief systems most strongly in this section and to resist that element in the way he presents his views and opinions. Do you think this makes his point stronger? How does this resistance to dogmatism relate to the seeming dichotomy he presents at the end of this section?