2. In this lesson I say that it should be clear that the discourse on nationalism is also about ethnicity and ideologies of “race.” If you trace the historical overview of nationalism in Canada in the CanLit guide, you will find many examples of state legislation and policies that excluded and discriminated against certain peoples based on ideas about racial inferiority and capacities to assimilate. – and in turn, state legislation and policies that worked to try to rectify early policies of exclusion and racial discrimination. As the guide points out, the nation is an imagined community, whereas the state is a “governed group of people.” For this blog assignment, I would like you to research and summarize one of the state or governing activities, such as The Royal Proclamation 1763, the Indian Act 1876, Immigration Act 1910, or the Multiculturalism Act 1989 – you choose the legislation or policy or commission you find most interesting. Write a blog about your findings and in your conclusion comment on whether or not your findings support Coleman’s argument about the project of white civility.

For this assignment, I decided to investigate the 1989 Canadian Multiculturalism Act. I was intrigued by this policy in particular because the BNA Act, Indian Act, and Immigration Act were all produced in a comparatively distant time period, which, although it does not lessen the horror of their implications and approaches, can seem cognitively distant enough that individuals attempt to tell themselves the governments that enacted those policies do not resemble ours and were more malicious than ours, which to me becomes dangerously close to the attitude of “that couldn’t happen here” or “that couldn’t happen now” that leads to individuals becoming complacent within their own democracies. In contrast, the Multiculturalism Act is relatively recent (occurring within the past 50 years), and at least on the surface level, seems far more positive in its approach to crafting a national identity than the BNA Act or the Indian Act, who explicitly attempt to control non-white groups and embrace colonial settlers as the dominant group.

The Canadian Multiculturalism Act of 1989 emerged in response to shifting social policies and opinions that worked to recognize the rights of various minority groups; in the 1960’s and 1970’s, this social movement included social forces like the Civil Rights movements in Canada and the US, the first and second wave feminist movements, and within Canada, Quebec’s Quiet Revolution. By 1989, an increasingly diverse Canadian population that grew with the help of immigration reform prioritizing skilled labour over country of origin began to fight for recognition by the Canadian government. Although general attitudes were becoming more inclusive, there was still little to no legal framework entrenching multiculturalism as a national value or as a legal framework through which to guide lawmakers and businesses.

However, while entrenching multiculturalism may initially seem like a positive action, recently questions have been raised about whether this action instead just identifies a sense of culturalism that relegates individual’s to their country or culture of origin, their observable heritage, or their families ethnic and cultural roots. This not only has the potential to emphasize cultural differences instead of similarities and empathy but also fails to identify the intersections or complexities of an individual’s upbringing. For example, how do you classify the culture of someone who had one parent grow up in France, the other in Kenya, both of whom then attended post-secondary in, say, England, before moving to Canada and raising a child together? (For an excellent discussion on this topic, and an alternative to asking ‘where are you from?’, see this video). There are many ways cultures intersect and diverge from the country of origin, and many cultures whose worldview does not center around borders, like the Indigenous people of Canada, whose presence in this land precedes even the concept of the nation-state.

Within the context of Coleman’s argument about creating a narrative of white civility, the fact that existing documentation was founded on a view of Canadian identity that was primarily limited to English and French in its recognition demonstrates the ways in which systematic frameworks were designed with whiteness as the priority. Similarly, the modifications to encourage diversity and inclusion through the Multiculturalism Act shows the disparities existing in the way minority and majority groups were treated; an explicit program to encourage diversity is necessary only in the backdrop of discrimination, and the ways in which this act identified minority groups further solidified this divide.

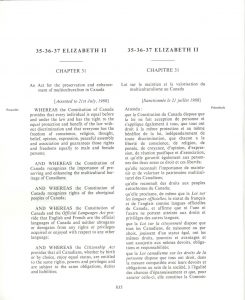

Library and Archives Canada. Statutes of Canada. An Act for the Preservation and Enhancement of Multiculturalism in Canada, 1988, SC 36-37 Elizabeth II, Volume I, Chapter 31. Retrieved from “Canadian Multiculturalism Act, 1988”.

Works Cited

“Canadian Multiculturalism Act, 1988.” Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, 2019, pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/canadian-multiculturalism-act-1988. Accesed 26 Feb 2019.

Dirks, Gerald. “Immigration Policy in Canada.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, 29 Jun 2017, thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/immigration-policy. Accessed 27 Feb 2019.

“Nationalism, 1960s onwards: Multiculturalism.” CanLit Guides, Canadian Literature Quarterly, 4 Oct 2016, canlitguides.ca/canlit-guides-editorial-team/nationalism-1960s-onwards-multiculturalism/. Accessed 26 Feb 2019.

“The Quiet Revolution.” Canada History, 2013, canadahistory.com/sections/eras/cold%20war/Quiet%20Revolution.html. Accessed Feb 26 2019.

Selasi, Taiye. “Don’t ask where I’m from, ask where I’m a local.” TEDGlobal, 2014, ted.com/talks/taiye_selasi_don_t_ask_where_i_m_from_ask_where_i_m_a_local/details?referrer=playlist-what_is_home&language=en. 26 Feb 2019.

Very interesting thoughts and thorough research.

I appreciate your hyperlink. It illuminates how despite long-since transitioning into an appreciation for Canadian ethnic diversity, the Multiculturalism Act actually began as a eurocentric effort to preserve a Canada which aspired to be European in culture.

From that hyperlink, you continued to say the Canadian Multicultural Act “emerged in response to shifting social policies and opinions that worked to recognize the rights of various minority groups […] like the […] second wave feminist movement.”

This is very interesting, because both The Multicultural Act and Second Wave Feminism share in the fact that despite ultimately accomplishing significant positive change for Canadian minorities, they both originate from an often untalked about and eurocentric history.

In the case of second wave feminism, I am thankful as a woman for the right to vote but offput by the terribly racist history behind the movement. What prompted second wave feminism in Canada was actually concern that Black men gaining the right to vote meant they would bring their “ethnic values” into Canadian legislature and culture. In result, white women took up a maternal feminism and fought for the right to vote not because they wanted the vote themselves –but because they wanted to preserve a white Canadian culture.

Here are some links showing how Nellie McClung (the iconic suffragette leader in Canada) was also a proud leader in eugenics (the science of breeding “idealized” humans and sterilizing “undesirable” human populations –often unwillingly):

1. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30031518?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

2. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/human-rights-lawyer-opposes-honour-for-right-to-vote-pioneer-nellie-mcclung/article1241485/

Nellie McClung herself authorized the unwitting sterilization of thousands of poor, ethnic, and disabled Canadians against their consent.

Hi Alexis,

Thank you for this interesting extension of my post. While I did know some details about how feminism as a movement has often had racism underlying its core, the information on Nellie McClung was new to me and has given me a lot to consider in how we have chosen to represent such “successes” as the suffragette movement in modern culture. Most of my education on women achieving the right to vote came from lessons in schools, which themselves are institutions that are tied to the government and have their own history of portraying specific ideologies and narratives as more dominant or more important than others. I think this is a fundamental example of how history is so often written by the victors, and to view the history we know as a form of fact can be a dangerous assumption — some of it is certainly true, but it is also explained by those who were given more power, more agency, and more control by that history. I am proud to be a woman who exercises her right to vote. I am proud to be a feminist. I am not proud of the ways both of those movements have so often prioritized the needs of white, upper-class women before trickling down to others, and as you have pointed out, have manipulated minority groups in order to further their own goal. I was taught that the right to vote was a win for women, but I was not taught the complicated intersections with race, class, and other hierarchies. Some of this information I have learned through my own research, but your post has reminded me that there is still so much more to learn and so much more progress that needs to be made.

Your post also made me think of the initiatives that are coming into place by teachers to make their classrooms more inclusive, representative, and diverse. (For some examples, see the following: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/education/history-canada-indigenous-education/article36157403/). Many provinces and schools have moved to include an Indigenous history component. What do you think will define whether these movements are successful? I also found this article to be really interesting in how it instructs teachers to incorporate Indigenous history into their classroom. https://www.edcan.ca/articles/truth-reconciliation-classroom/. How is it successful in demonstrating integration, and where does it fall short?

Hi Charlotte,

Thank you for your research and interesting hyperlink to the Ted talk of Talyse Selasi talking about the “multi-local” people. I did my assignment on Canadian Immigration Act so it was interesting to read about the Multiculturalism Act. Immigration Act inhibited immigration rather than prohibiting and discriminated immigrants based on race, ethnicity and national origin. I would’ve thought that Multiculturalism Act would have shifted the social policies on being more inclusive, but as you mentioned it may have instead identified a sense of culturalism that relegates individual to their country or culture of origin. I watched Talyse Selasi’s Ted talk and it was interesting how she mentioned that we cannot come from a nation which is a concept because country is not fixed, constant but countries can disappear over time, born, die, expand and contract. When I am introducing myself to others, I’m always introducing where I am from which is Korea because I was born there but I have spent more time growing up in Canada and I hold both Canadian passport and Korean passport. So, what does that make me? Her talk made me think about the assignment where we had to write about our home. Many of us carried different experiences at different places and were multi-local. It was the experiences that identified people’s sense of home and identity, it was not about where they were born and which passport they held. As Talyse Selasi says “You can take away my passport but you can’t take away my experience that I carry with me, where I’m from comes wherever I go” Passports do not define our identify but our experiences do, so it made me wonder, does the question of “Where are you from?” really tell anything about a person? Maybe that question is not necessary to ask to a person if you are trying to get to know about the person and understanding them.

Hi Cathy,

Thank you for your thoughts! I really enjoyed the ways you were able to tie this post into past lessons and assignments, as that talk also had me thinking of the home assignment. I am glad to be able to expand on that a little here.

I was really intrigued by the point you identified wherein Talyse Selasi acknowledges that countries themselves are not fixed entities. they change over history, have divides, wars, and successes that shape their borders and their associations with the people within them. I find the concept of borders to be very strange – we assign a division, rather than embracing similarities. I think Selasi identifies the importance of experience in shaping a person, much more than location, which can also connect to the ways in which many of our lessons have focused on the importance of the narratives we tell about others and ourselves. I think the arc of one’s life, and the way it connects to those of others, is far more representative of a person and their “roots” than the country on their passport, although country may or may not play an important role to someone on an individual basis.

The idea of the Multiculturalism Act as both positive and negative can also be seen through this land. On one hand, it formally acknowledges that “Canadians” are united through something beyond the location of upbringing, enshrining a belief in coming together regardless of country of origin. However, this also necessitates recognizing differences in one’s person due to ethnic and cultural origins, and it relies on an idea of “canadiannness” as requiring shared values. Prescribing an ideology in order to create a whole identity, while perhaps well-meaning, also raises complex questions about who was given the power to decide what those values are and how they operate. Unfortunately, this question cannot be isolated from concepts of class, race, and colonial history. We need to continue to unravel these ties before we can decide how to appropriately handle conversations about Canadian identity, Canadian history, and cultural identity.

Hi Charlotte,

I found your post very interesting, especially the part which discussed asking the question about where are you from. As you explained, how does one answer if they are a mixture os so many different places, nationalities and cultures.

I would push this one further and argue to ask where does one say they’re from if they attribute their identity so something that isn’t a place. For example, when anyone asks me where I am from, I respond that I am an Eastern European Jew, as the countries that my family left before the war are insignificant (especially because the borders were changing so many at that time, it is hard to know where they exactly were from). Therefore I would push the comment even further that the Ted Talk video (Also amazing link, thank you for sharing) and say that you should as people what is their background.

Thanks

Sandra