For this assignment, I chose to analyze pages 187-199 of Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water because of the rich allusions to literary and historical figures seen throughout. These segments engage intertextually with key literary figures and authors, drawing attention to the practice of constructing narrative that we see throughout King’s work. Additionally, we get scenes of engagement between creation stories, re-writing various narratives of dominance, and King’s classic ability to question which stories our culture promotes by offering alternative points of view and giving voice to minor characters. I’ve decided to approach these analyses chronologically rather than categorically so that it is easier for anyone reading this to follow along in their own copy, and because King so cleverly rejects traditional linear structure that approaching it in any other manner seemed ineffectual. King invites us along on the journey as he writes it, and in this sense, I’m following directions.

Bill Bursum complains about titles and naming: As Jane Flick demonstrates, Bill Bursum’s name refers to two historical figures who shared a detestation for Indigenous people in what is now the United States: Holm Bursum, who proposed the Bursum Bill that divested land in order to give it to non-Indigenous peoples for development, and Buffalo Bill Cody, who exploited Indigenous people through Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West and served as a Union scout to fight against the Kiowa and Comanche. These allusions highlight King’s concern with media, narrative, and stereotyping. The character himself engages in simplistic thinking around Indigenous issues; he refers to Indigenous peoples as Indians, which itself comes from colonial history and Cristopher Columbus’s mistakenly thinking he had arrived in India when he arrives in North America. He also complains that you can no longer use the term Indian, and “when some smart college professor did come up with a really good name like Amerindian, the Indians didn’t like it;” this may be a reference to controversial activist Ward Churchill and others involved with the American Indian Movement. Bill Bursum even goes so far as to say Lionel and Charlie “aren’t really Indians any more”

That nut in Montreal: The direct reference here is unclear, but given the timing of the novel’s publication in 1993, this could be a reference to the mass shooting of 14 women studying engineering at École Polytechnique in 1989, the Concordia University massacre in 1992, or potentially an indirect reference to various events in the Oka Crisis, which involved land disputes between the Mohawk people and the Canadian government and Montreal Mayor bringing in Canadian police forces to fight against the Mohawk people.

The Mysterious Warrior and Monument Valley: Jane Flick writes that this is a composite of key Western movies and actors combined to allude to The Mystic Warrior, whose source material caused controversy due to its misrepresentation of indigenous people. This allusion is reinforced by writings about a film shot across monument valley, which Flick elucidates is a reference to Stagecoach, which placed John Wayne on the map as a Western film star.

George Wears the Fringed Leather Jacket: We know from Jane Flick that George’s name refers indirectly to George Armstrong Custer, a general in the Civil War and American Indian Wars, where he took part in massacres and attacks against the Cheyenne and Lakota Sioux in particular. The jacket he wears alludes to a photo mentioned earlier in the novel where Custer poses in a fringed jacket. George even states that the jacket and matching gloves “belonged to one of [his] relatives,” and tells Latisha, “Most old things are worthless. This is history,” heightening the allusion. The violence George commits against Latisha in this jacket evokes the violence General Custer enacted against Indigenous people, particularly as Latisha herself is Indigenous.

“Mom, is this the one where the cavalry comes over the hill and kills the Indians?”: Likely another reference to General Custer and his role in the seventh cavalry in particular.

Changing Woman, the White Whale, and the White Canoe: The white whale is a clear reference to Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick and the white whale its main character hunts throughout the novel. By referencing this book, King brings forth another key literary force about violence, dominance, and competition. Changing Woman mentions the white canoe seen in previous chapters, which alluded to Noah’s Ark; placing this in the context of the hunted whale puts the Christian story under attack.

The Pequod: As Jane Flick mentions, the Pequod is both the name of the ship Ahab captains in Moby Dick, and closely resembles the name of the Indigenous Pequot tribe.

Ishmael and Queequeg: “Call me Ishmael” is the opening line of Moby Dick, and Queequeg is an indigenous character within Moby Dick. Queequeg is an explorer and is the first person Ishmael encounters in the novel. They develop a friendship; however, Queequeg is also a wild, unpredictable, tattooed cannibal. Melville attempts to incorporate a ship-based democracy in Moby Dick, incorporating Queequeg into its inner workings. A coffin Queequeg builds for himself acts as a life preserver for Ishmael (For a full analysis of Queequeg’s character, see here or find reference below for Vanderbeke); King seems to manipulate the representation of Native people as savage and as serving white men when the Changing Woman takes on this role.

Coyote’s Favourite Months: Coyote says he likes the months April and July, but doesn’t like November. New coyote pups emerge in April, gain independence and begin exploring in July, and November is a popular month for humans to hunt coyotes as their fur coat grows thicker; this brings forth the imagery of white men hunting indigenous people just as their trickster figure is hunted, reinforced by the hunting narrative of Moby Dick that is prominent in this section.

Whaleswhaleswhalesbians and Blackwhaleblackwhaleblackwhalesbians: not necessarily a direct reference, but the incorporation of the hunted whale as black, female, and apparently lesbian evokes the attack of white men and majorities against minority people. In this way, King highlights how the narratives of white, often male, dominance have evolved to attack modern-day minorities, but have not progressed to equality. As Moby-Jane says, “he always comes back.” Placing Changing Woman in the role of Queequeg, but having her refuse to attack the whale and swim with it instead of becoming a harpooner, creates a narrative in which Indigenous people support other minorities and live collectively, rather than combatively.

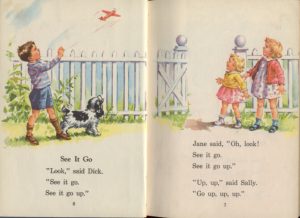

Moby-Dick the White Whale and Moby-Jane the Black Whale: The use of Moby-Dick and Moby-Jane could be seen as alluding the childhood basal textbook series Dick and Jane, popular in the 1930s onwards. Basal textbooks are designed to teach children manners, customs, and how to engage in the world, along with teaching skills like reading and writing. Dick and Jane books became iconic in America by the 1950s, and now hold a place of both nostalgia and criticism from many for being misogynistic and lacking diversity. Manipulating these traditionally white, privileged, instructional children’s names into a tale of revolution against the dominant power structures suggests an entirely different kind of education and teaching. King uses a narrative used to teach children about the world into one that teaches resistance, collaboration, and uprooting power structures.

An excerpt from a Dick and Jane book, retrieved from the “Reading with and without Dick and Jane” Rare Book School Exhibit

Works Cited

“Buffalo Bill Cody.” Biography, 27 April 2017, biography.com/people/buffalo-bill-cody-9252268. Accessed 17 Mar 2019.

Chavers, Dean. “5 Fake Indians: Checking a Box Doesn’t Make You Native.” Indian Country Today, 15 Oct 2014, newsmaven.io/indiancountrytoday/archive/5-fake-indians-checking-a-box-doesn-t-make-you-native-Z9mn2ErpHEWl5BDNU9LJRw/. Accessed 17 Mar 2019.

“Custer and 7th Cavalry attacked by Indians.” This Day in History, HISTORY, 25 Feb 2019, history.com/this-day-in-history/custer-and-7th-cavalry-attacked-by-indians. Accessed 17 Mar 2019.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161/162 (1999). Web. 15 Mar. 2019

“Furbearer Management Guidelines.” British Columbia Wildlife, env.gov.bc.ca/fw/wildlife/trapping/docs/coyote.pdf. Accessed 16 Mar 2019.

“George Armstrong Custer.” HISTORY, 21 Aug 2018, history.com/topics/native-american-history/george-armstrong-custer. Accessed 18 Mar 2019.

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers, 1993. pp. 187-199. Print.

Lejtenyi, Patrick. “The Toxic Masculinity Behind One of Canada’s First University Shootings.” VICE, 6 April 2017, vice.com/en_ca/article/gve754/the-toxic-masculinity-behind-one-of-canadas-first-university-shootings. Accessed 16 Mar 2019.

Martinez, Matthew. “All Indian Pueblo Council and the Bursum Bill.” New Mexico History.Org, newmexicohistory.org/people/all-indian-pueblo-council-and-the-bursum-bill. Accessed 17 Mar 2019.

Melville, Herman. Moby Dick. Edited by Will Eisner, NBM, 2001.

“Montreal Massacre: Legacy of Pain.” CBC’s The Fifth Estate, 1 Dec 1999, cbc.ca/fifth/episodes/40-years-of-the-fifth-estate/montreal-massacre-a-legacy-of-pain. Accessed 18 Mar 2019.

MovieClips Classic Trailers. “Stagecoach (1939) Official Trailer – John Wayne, John Ford Western Movie HD.” YouTube, 26 Jun 2014, youtu.be/gK645_7TA6c. Accessed 18 Mar 2019.

“The Oka Crisis.” CBC Digital Archives, 2018, cbc.ca/archives/topic/the-oka-crisis. 18 Mar 2019.

Shermer, Elizabeth. “Reading with and withoutDick and Jane. The politics of literacy in c20 America.” Rare Book School, Nov 1 2003, rarebookschool.org/2005/exhibitions/dickandjane.shtml. Accessed 18 Mar 2019.

Vanderbeke, Dirk. “Queequeg’s Voice: Or, Can Melville’s Savages Speak?” Leviathan, vol. 13, no. 1, 2011, pp. 59-73.

Wallenfeldt, Jeff. “Pequot: History, War, 7 Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 6 Dec 2018, britannica.com/topic/Pequot. Accessed 17 Mar 2019.

Ward, Jervette. “In Search of Diversity: Dick and Jane and Their Black Playmates.” ACADEMIA, academia.edu/1943895/_In_Search_of_Diversity_Dick_and_Jane_and_Their_Black_Playmates_. Accessed 17 Mar 2019.

“William F. Cody: Buffalo Bill.” New Perspectives on The West, 2001, pbs.org/weta/thewest/people/a_c/buffalobill.htm. Accessed 16 Mar 2019.

HI Charlotte.

It was wonderful to read your blog. It is so enlightening to follow you deep into readings of King’s intertextual references. There were quite a few that . I had not picked up on really made me think more deeply about the novel and its meaning. For instance, your section on Moby Dick and Moby Jane was particularly fascinating in the way you link King’s reference to Toni Morrison’s deconstruction of the racist subtext of the traditional children’s story.

This was personally relevant to me as I am currently in South Africa with my African-Canadian wife and our racially mixed daughter. (who is only 7months old). I am therefore extremely racially conscious and aware that my child is currently growing up in a world where the stories, images, and entire educational system favours one part of her identity. My question for you is what you see as King’s approach to this problem. Is he suggesting we must make every effort to uproot old stories by infusing them with indigenous and racially diverse content? Or is there a need for a total, and more through subversion that will go to the root and change the entire education system ?

Hi Laen,

Thank you for your comment, and for sharing about your family’s experiences with the way our world currently engages with race. I think your question is complicated and multi-faceted, and I would hesitate to state that King offers a singular solution. I think there is a tendency in the Western world to look to one key person of colour to have the answers to how to “fix” racism, which King actively disengages with in his work by presenting multiple histories, storylines, approaches, flawed and strong characters, and messages. Given King’s considerations of disrupting Western style and linearity, I don’t think there is one consistent method he suggests.

That being said, I definitely think some of the patterns that King uses in his writing carry certain messages with them. The way King uses manipulations of dominant narratives (ie all the allusions to biblical figures in particular) seem like they are designed to get people to question and consider how they came to hold the beliefs they did, and to be confronted with the fact that many of these beliefs have flaws, and also that there are alternative belief systems that are not inherently inferior, but have been relegated to a place of inferiority by the dominant culture.

I think rather than saying we must uproot certain narratives, King challenges us to engage extremely critically with them, to interrogate what we are taught and what we have learned to believe, and to pay attention to what messages are embraced and taught to us. This seems like an individual process King is asking his readers to engage with, but one that, like his writing, extends beyond the boundary of the text; interrogating these beliefs requires engaging in a dialogue with dominant media, narratives, cultures, and yourself. It is an inherently collaborative process, just like challenging the dominant structures and institutions we live in requires collaboration.

Hi Charlotte,

Thank you for a fantastic blog post! It was really refreshing to see such detailed analysis on not only characters, but also dialogues and concepts. You did an amazing job and cite a variety of references for each example.

For your example on Ishmael, you mention that this reference is from Moby Dick, something that is also described in Jane Flick’s reading notes. Do you think that Ishmael in this context could also allude to Ishmael from the Bible (i.e. Abraham’s son)? I am curious to know your opinion. King makes several allusions to Christianity (e.g. Ahdamn and Adam) so I would not be surprised if this is another case of a reference to that religion.

Hi Simran,

I definitely think this could be an instance where King’s use of allusions has a double-reference or multilayering. You pointed out the multitude of biblical figures King uses already, and Ishmael would certainly fit into King’s use of these characters to satirize and criticize Judeo-Christian religious narratives due to their role in colonization. King highlights the differences between these views and Indigenous worldviews throughout the novel, so it would certainly be within the literary scope he takes to also have Ishmael represent the Biblical figure.

Additionally, I believe Melville himself chose the name Ishmael due to its biblical roots; Ishmael is a bit of an outcast in the biblical tradition and Ishmael in Moby Dick separates from society in pursuit of a seemingly-pointless hunt for the white whale. They both also share an ability to gather followers, often similarly outcast. Considering Melville chose the name with some level of intentionality, I would be surprised if King didn’t also choose it due to its connotations.

Upon more thought, I also think it’s interesting that King uses the opening line — “Call me Ishmael” — in his text; many scholars have drawn attention to the particular phrasing of this; he doesn’t say “My name is Ishmael” or “I’m Ishmael,” he specifically instructs others to CALL him Ishmael, which creates a sense of veiled truth, suspicion, or duplicity. King could easily be playing on this duplicity given the way he shows many religions and Western viewpoints as hypocritical or double-sided as well.

Hi Charlotte,

Great blog, the depth of your analysis made it a joy to read. Your allusions really do highlight the power relations and racial references of white dominance in many stories. Specifically looking at the Moby-Dick and Moby-Jane allusion, I never thought about how the names were connected to Dick and Jane. I remember reading an article once relating to “Dick and Jane” and how it depicts an image of white perfection. An almost utopian lifestyle. I think King was trying to draw on that theme too in how white characters often get symbolized as perfection while minorities would never get the same portrayal.

Hi Kynan,

Thank you for your comments and your kind words! I thought the Dick and Jane reference was rather subtle, but one of my aunts was a teacher and had a number of the books still lying around her home when I was a kid, so the names happened to jump out at me. I definitely agree that the image of white perfection in Dick and Jane is playing into the narrative and criticism King constructs. I also think it brings forth the idea of indoctrination, given its an instructional booklet for and about children. He subverts almost all elements of this utopianism; the humans become animals, the utopian children are hunted and resistant, and the adult figures become threatening, rather than educating and nurturing.