For this assignment, I chose to analyze pages 187-199 of Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water because of the rich allusions to literary and historical figures seen throughout. These segments engage intertextually with key literary figures and authors, drawing attention to the practice of constructing narrative that we see throughout King’s work. Additionally, we get scenes of engagement between creation stories, re-writing various narratives of dominance, and King’s classic ability to question which stories our culture promotes by offering alternative points of view and giving voice to minor characters. I’ve decided to approach these analyses chronologically rather than categorically so that it is easier for anyone reading this to follow along in their own copy, and because King so cleverly rejects traditional linear structure that approaching it in any other manner seemed ineffectual. King invites us along on the journey as he writes it, and in this sense, I’m following directions.

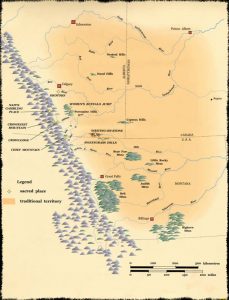

Bill Bursum complains about titles and naming: As Jane Flick demonstrates, Bill Bursum’s name refers to two historical figures who shared a detestation for Indigenous people in what is now the United States: Holm Bursum, who proposed the Bursum Bill that divested land in order to give it to non-Indigenous peoples for development, and Buffalo Bill Cody, who exploited Indigenous people through Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West and served as a Union scout to fight against the Kiowa and Comanche. These allusions highlight King’s concern with media, narrative, and stereotyping. The character himself engages in simplistic thinking around Indigenous issues; he refers to Indigenous peoples as Indians, which itself comes from colonial history and Cristopher Columbus’s mistakenly thinking he had arrived in India when he arrives in North America. He also complains that you can no longer use the term Indian, and “when some smart college professor did come up with a really good name like Amerindian, the Indians didn’t like it;” this may be a reference to controversial activist Ward Churchill and others involved with the American Indian Movement. Bill Bursum even goes so far as to say Lionel and Charlie “aren’t really Indians any more”

That nut in Montreal: The direct reference here is unclear, but given the timing of the novel’s publication in 1993, this could be a reference to the mass shooting of 14 women studying engineering at École Polytechnique in 1989, the Concordia University massacre in 1992, or potentially an indirect reference to various events in the Oka Crisis, which involved land disputes between the Mohawk people and the Canadian government and Montreal Mayor bringing in Canadian police forces to fight against the Mohawk people.

The Mysterious Warrior and Monument Valley: Jane Flick writes that this is a composite of key Western movies and actors combined to allude to The Mystic Warrior, whose source material caused controversy due to its misrepresentation of indigenous people. This allusion is reinforced by writings about a film shot across monument valley, which Flick elucidates is a reference to Stagecoach, which placed John Wayne on the map as a Western film star.

George Wears the Fringed Leather Jacket: We know from Jane Flick that George’s name refers indirectly to George Armstrong Custer, a general in the Civil War and American Indian Wars, where he took part in massacres and attacks against the Cheyenne and Lakota Sioux in particular. The jacket he wears alludes to a photo mentioned earlier in the novel where Custer poses in a fringed jacket. George even states that the jacket and matching gloves “belonged to one of [his] relatives,” and tells Latisha, “Most old things are worthless. This is history,” heightening the allusion. The violence George commits against Latisha in this jacket evokes the violence General Custer enacted against Indigenous people, particularly as Latisha herself is Indigenous.

“Mom, is this the one where the cavalry comes over the hill and kills the Indians?”: Likely another reference to General Custer and his role in the seventh cavalry in particular.

Changing Woman, the White Whale, and the White Canoe: The white whale is a clear reference to Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick and the white whale its main character hunts throughout the novel. By referencing this book, King brings forth another key literary force about violence, dominance, and competition. Changing Woman mentions the white canoe seen in previous chapters, which alluded to Noah’s Ark; placing this in the context of the hunted whale puts the Christian story under attack.

The Pequod: As Jane Flick mentions, the Pequod is both the name of the ship Ahab captains in Moby Dick, and closely resembles the name of the Indigenous Pequot tribe.

Ishmael and Queequeg: “Call me Ishmael” is the opening line of Moby Dick, and Queequeg is an indigenous character within Moby Dick. Queequeg is an explorer and is the first person Ishmael encounters in the novel. They develop a friendship; however, Queequeg is also a wild, unpredictable, tattooed cannibal. Melville attempts to incorporate a ship-based democracy in Moby Dick, incorporating Queequeg into its inner workings. A coffin Queequeg builds for himself acts as a life preserver for Ishmael (For a full analysis of Queequeg’s character, see here or find reference below for Vanderbeke); King seems to manipulate the representation of Native people as savage and as serving white men when the Changing Woman takes on this role.

Coyote’s Favourite Months: Coyote says he likes the months April and July, but doesn’t like November. New coyote pups emerge in April, gain independence and begin exploring in July, and November is a popular month for humans to hunt coyotes as their fur coat grows thicker; this brings forth the imagery of white men hunting indigenous people just as their trickster figure is hunted, reinforced by the hunting narrative of Moby Dick that is prominent in this section.

Whaleswhaleswhalesbians and Blackwhaleblackwhaleblackwhalesbians: not necessarily a direct reference, but the incorporation of the hunted whale as black, female, and apparently lesbian evokes the attack of white men and majorities against minority people. In this way, King highlights how the narratives of white, often male, dominance have evolved to attack modern-day minorities, but have not progressed to equality. As Moby-Jane says, “he always comes back.” Placing Changing Woman in the role of Queequeg, but having her refuse to attack the whale and swim with it instead of becoming a harpooner, creates a narrative in which Indigenous people support other minorities and live collectively, rather than combatively.

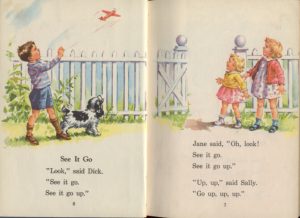

Moby-Dick the White Whale and Moby-Jane the Black Whale: The use of Moby-Dick and Moby-Jane could be seen as alluding the childhood basal textbook series Dick and Jane, popular in the 1930s onwards. Basal textbooks are designed to teach children manners, customs, and how to engage in the world, along with teaching skills like reading and writing. Dick and Jane books became iconic in America by the 1950s, and now hold a place of both nostalgia and criticism from many for being misogynistic and lacking diversity. Manipulating these traditionally white, privileged, instructional children’s names into a tale of revolution against the dominant power structures suggests an entirely different kind of education and teaching. King uses a narrative used to teach children about the world into one that teaches resistance, collaboration, and uprooting power structures.

An excerpt from a Dick and Jane book, retrieved from the “Reading with and without Dick and Jane” Rare Book School Exhibit

Works Cited

“Buffalo Bill Cody.” Biography, 27 April 2017, biography.com/people/buffalo-bill-cody-9252268. Accessed 17 Mar 2019.

Chavers, Dean. “5 Fake Indians: Checking a Box Doesn’t Make You Native.” Indian Country Today, 15 Oct 2014, newsmaven.io/indiancountrytoday/archive/5-fake-indians-checking-a-box-doesn-t-make-you-native-Z9mn2ErpHEWl5BDNU9LJRw/. Accessed 17 Mar 2019.

“Custer and 7th Cavalry attacked by Indians.” This Day in History, HISTORY, 25 Feb 2019, history.com/this-day-in-history/custer-and-7th-cavalry-attacked-by-indians. Accessed 17 Mar 2019.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161/162 (1999). Web. 15 Mar. 2019

“Furbearer Management Guidelines.” British Columbia Wildlife, env.gov.bc.ca/fw/wildlife/trapping/docs/coyote.pdf. Accessed 16 Mar 2019.

“George Armstrong Custer.” HISTORY, 21 Aug 2018, history.com/topics/native-american-history/george-armstrong-custer. Accessed 18 Mar 2019.

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers, 1993. pp. 187-199. Print.

Lejtenyi, Patrick. “The Toxic Masculinity Behind One of Canada’s First University Shootings.” VICE, 6 April 2017, vice.com/en_ca/article/gve754/the-toxic-masculinity-behind-one-of-canadas-first-university-shootings. Accessed 16 Mar 2019.

Martinez, Matthew. “All Indian Pueblo Council and the Bursum Bill.” New Mexico History.Org, newmexicohistory.org/people/all-indian-pueblo-council-and-the-bursum-bill. Accessed 17 Mar 2019.

Melville, Herman. Moby Dick. Edited by Will Eisner, NBM, 2001.

“Montreal Massacre: Legacy of Pain.” CBC’s The Fifth Estate, 1 Dec 1999, cbc.ca/fifth/episodes/40-years-of-the-fifth-estate/montreal-massacre-a-legacy-of-pain. Accessed 18 Mar 2019.

MovieClips Classic Trailers. “Stagecoach (1939) Official Trailer – John Wayne, John Ford Western Movie HD.” YouTube, 26 Jun 2014, youtu.be/gK645_7TA6c. Accessed 18 Mar 2019.

“The Oka Crisis.” CBC Digital Archives, 2018, cbc.ca/archives/topic/the-oka-crisis. 18 Mar 2019.

Shermer, Elizabeth. “Reading with and withoutDick and Jane. The politics of literacy in c20 America.” Rare Book School, Nov 1 2003, rarebookschool.org/2005/exhibitions/dickandjane.shtml. Accessed 18 Mar 2019.

Vanderbeke, Dirk. “Queequeg’s Voice: Or, Can Melville’s Savages Speak?” Leviathan, vol. 13, no. 1, 2011, pp. 59-73.

Wallenfeldt, Jeff. “Pequot: History, War, 7 Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 6 Dec 2018, britannica.com/topic/Pequot. Accessed 17 Mar 2019.

Ward, Jervette. “In Search of Diversity: Dick and Jane and Their Black Playmates.” ACADEMIA, academia.edu/1943895/_In_Search_of_Diversity_Dick_and_Jane_and_Their_Black_Playmates_. Accessed 17 Mar 2019.

“William F. Cody: Buffalo Bill.” New Perspectives on The West, 2001, pbs.org/weta/thewest/people/a_c/buffalobill.htm. Accessed 16 Mar 2019.