- In order to tell us the story of a stereo salesman, Lionel Red Deer (whose past mistakes continue to live on in his present), a high school teacher, Alberta Frank (who wants to have a child free of the hassle of wedlock—or even, apparently, the hassle of heterosex!), and a retired professor, Eli Stands Alone (who wants to stop a dam from flooding his homeland), King must go back to the beginning of creation. Why do you think this is so?

In reading the novel, I was struck by the ways in which King uses the structure of his work to disorient the reader from their traditional styles of analysis and interpretation. The non-linear format relies heavily on seemingly disconnected stories, jumping location, narration, and chronology frequently; this challenges the reader to immediately disregard the conventions of storytelling they are used to, creating a space where King pushes the boundaries of Western narrative forms and therefore asking the readers to embrace and consider alternative narratives. With this context, his decision to return to the creation story is unusual in that it grounds the narrative within a fixed point: the beginning. This creates a central focus around which the seemingly conflicted narratives all share a developmental arc, and, given that the stories of Alberta Frank, Eli Stands Alone, and Lionel Red Deer are eventually connected, creates a sense of the individual stories as bound in a shared universe that is interconnected through its stories and their shared beginning.

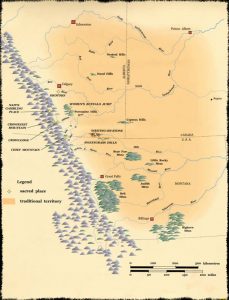

Additionally, King seems to use the creation stories to challenge our predetermined inclinations to view the world in binary terms; we get interactions between characters from Indigenous belief systems and those from Christian systems, presenting the idea of a world that has space for multiple belief systems to coexist in a legitimate, interconnected way. Although much of King’s writing about the Judeo-Christian narrative involves irony and tongue-in-cheek expressions, the dialogue existing between God and Coyote shows a shared understanding of the duplicity of religious beliefs and worldviews. King creates a dialogue that shows alternate views of creation, tied together in one initial moment. They are not necessarily in competition, but rather both existing in a similar experience of the world (even if at times King uses the Judeo-Christian God as a criticism or caricature of this worldview). The novel is also set in primarily Blackfoot territory, and the Blackfoot have a variety of creation stories involved in their own worldview; King’s choice is therefore not insignificant in the way it interplays with the other characters and other creation stories.

Map of Traditional Blackfoot Territory, Retrieved from the Glenbow Museum

Indigenous worldviews rely heavily on a perspective of interconnection, which views the world and the living and non-living creatures within it as fundamentally connected through their actions, narratives, and shared use of the land. A fundamental element of this interconnected worldview comes from the belief in a shared story of creation, which, as we have discussed in past lessons, itself relies on communication and collaboration between animals, people, and sometimes the land itself. I am thinking in particular of the story of The Woman Who Fell From the Sky, wherein creation involves not only the woman herself, the birds who help break her fall, the turtle arising from the water to give her a place to sit, the otters and muskrats who dive to get the mud to form the earth, and the twins she births, who create a balance between light, darkness, order, and chaos in the world. This worldview is holistic, finding a balance in all elements of the world; King shows a similar representation of seemingly unrelated events as fundamentally connected not only through the novel’s conclusion but also through the importance of creation in his storytelling. Although King uses the Coyote myth, the fundamental balance between different forces and the interconnection fundamental to many indigenous worldviews is still essential in his writing.

Works Cited

Ashliman, D.L. “Blackfoot Creation and Origin Myths.” FolkTexts, 4 Jan 2003, pitt.edu/~dash/blkftcreation.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2019.

Blackfoot Traditional Territory Map. Glenbow Museum online, glenbow.org/blackfoot/maps/traditional_territory_map.htm. Accessed 7 Mar 2019.

“Interconnectedness.” First Nations Pedagogy Online, 2009, firstnationspedagogy.ca/interconnect.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2019.

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

“Traditional Stories.” Niitsitapiisini: Our Way of Life, Glenbow Museum Online, 2019, glenbow.org/blackfoot/EN/html/traditional_stories.htm. Accessed 7 Mar 2019.

“Woman Who Fell From The Sky.” Myths Encyclopedia, 2019, mythencyclopedia.com/Wa-Z/Woman-Who-Fell-From-the-Sky.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2019.