Imagining alternative futures for coastal landscapes requires not only new infrastructural strategies but also a paradigm shift in terms of how people relate to the water around them. Climate change also raises questions about the value of non-human nature, and whether we have a moral obligation to protect certain, if not all species. What is the role of design in assisted migration of plants and animals? Which communities and cultural landscapes are prioritized when it comes to coastal protection? In order to answer these questions, we must seek to understand and experience other, non-anthropocentric ways of seeing and being in this world.

In this context, much can be learned from Indigenous communities that have lived for centuries on the land-water interface. Indigenous peoples have cultivated a deep and nuanced understanding of human-nonhuman relationships, which are embedded in a wide range of site-specific landscape technologies and management strategies that have been passed down through generations, and evolved over time.

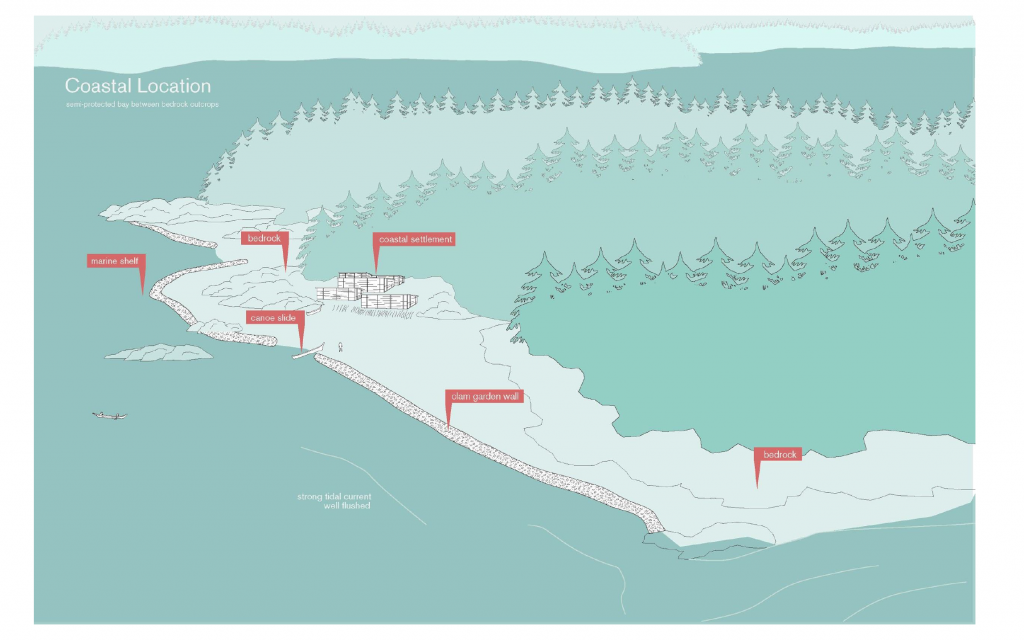

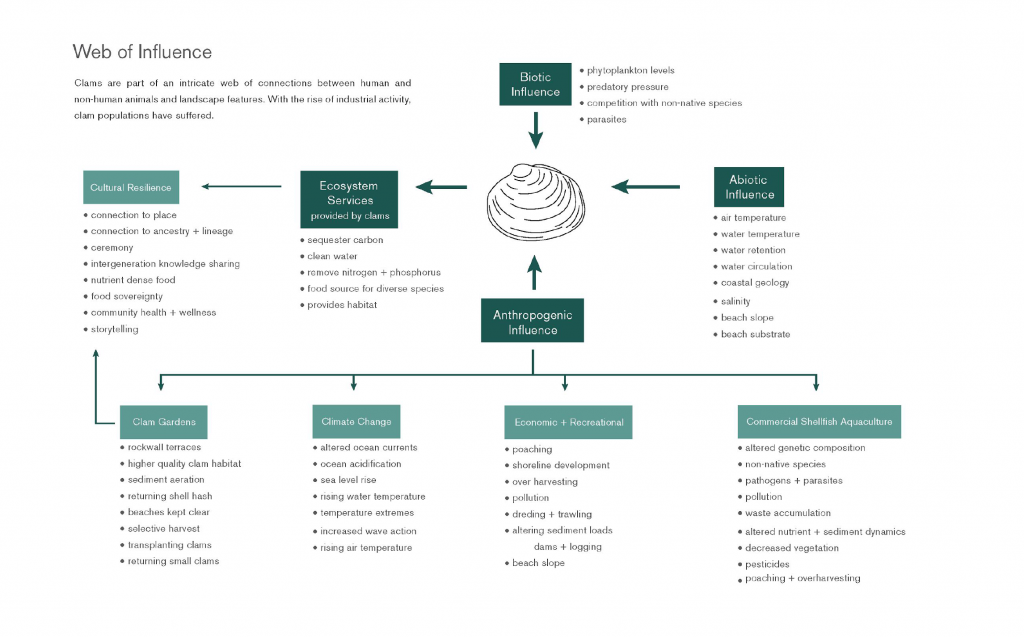

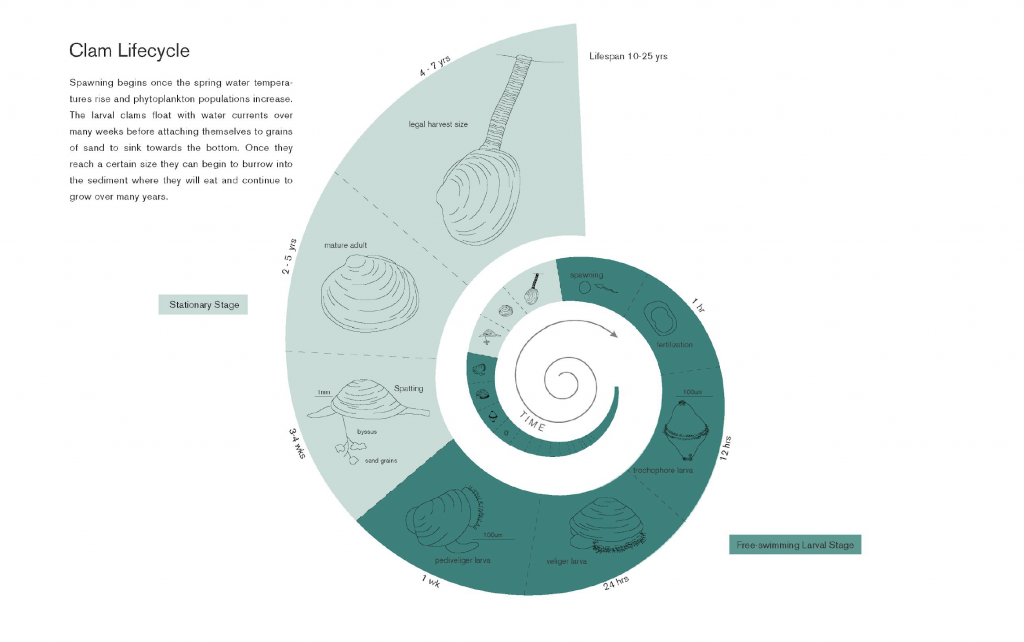

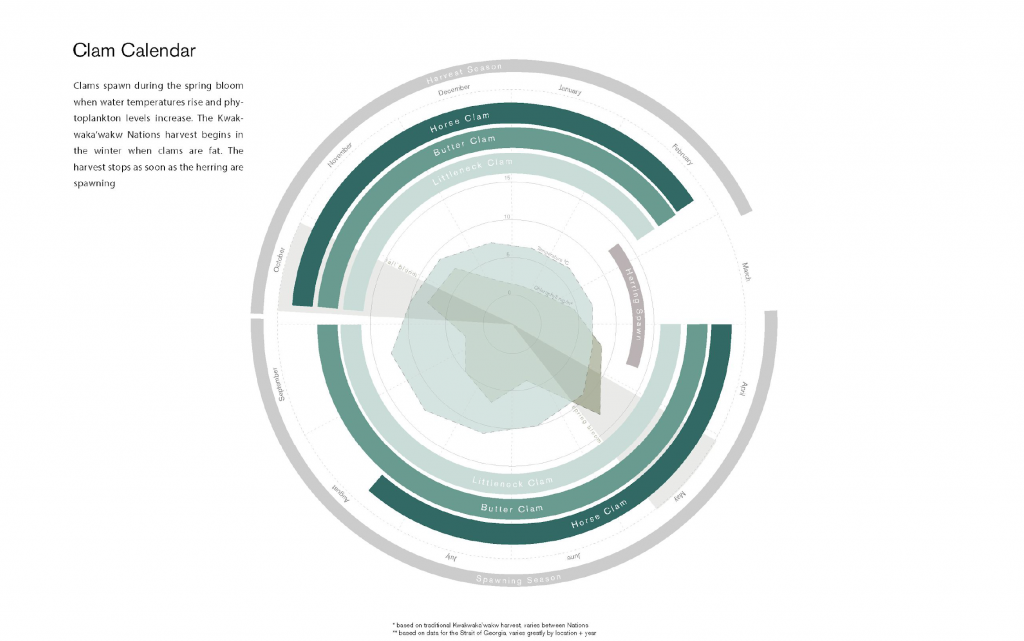

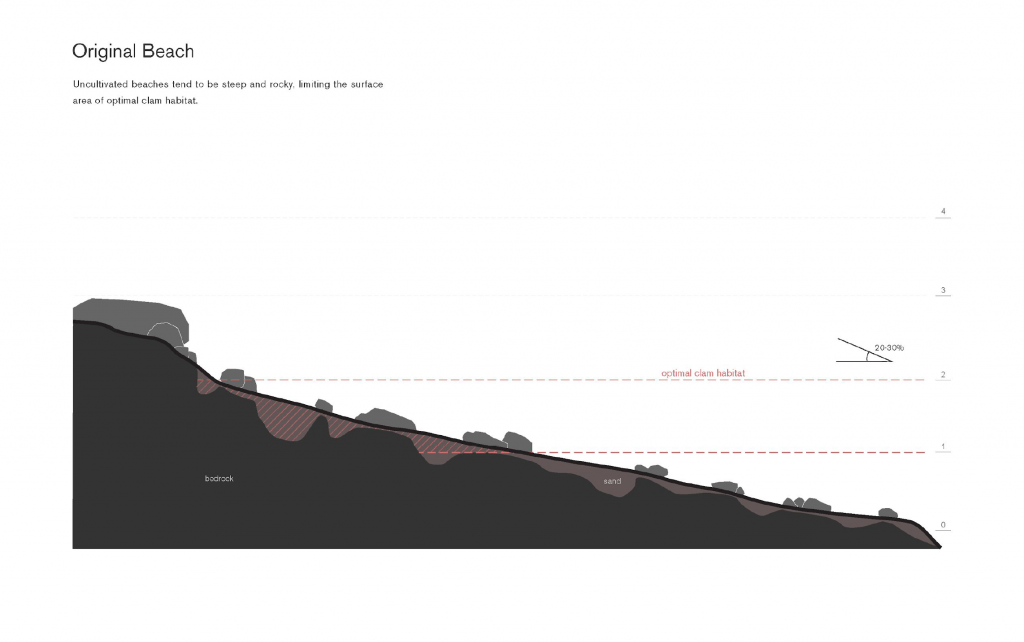

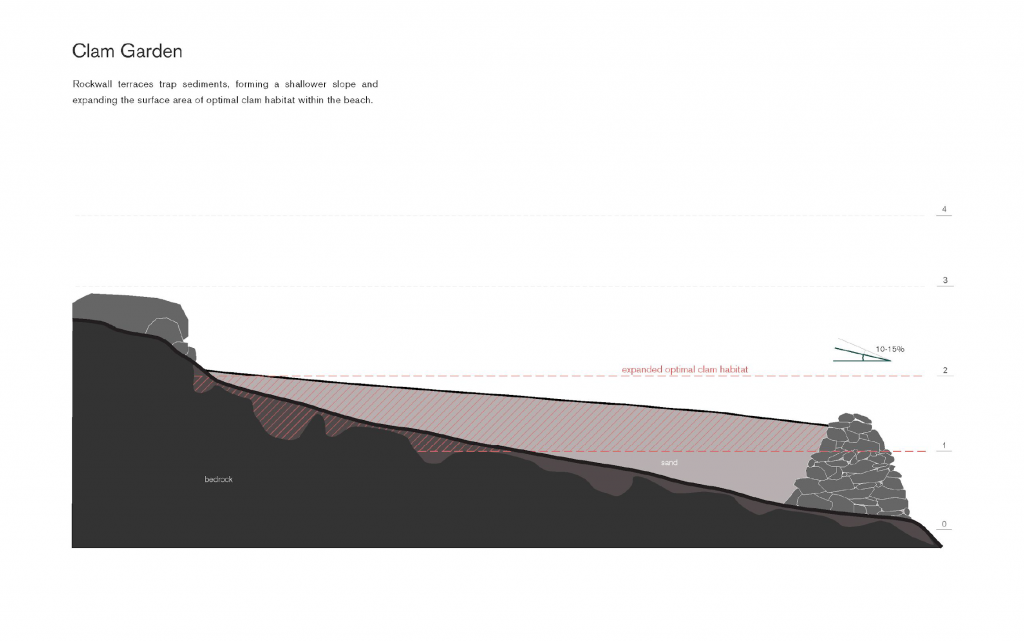

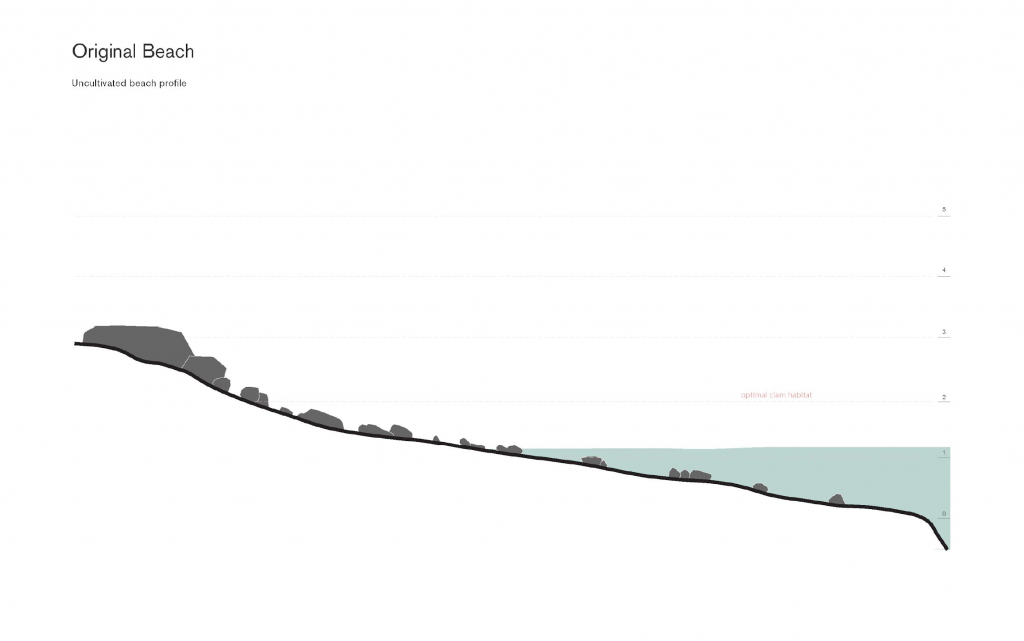

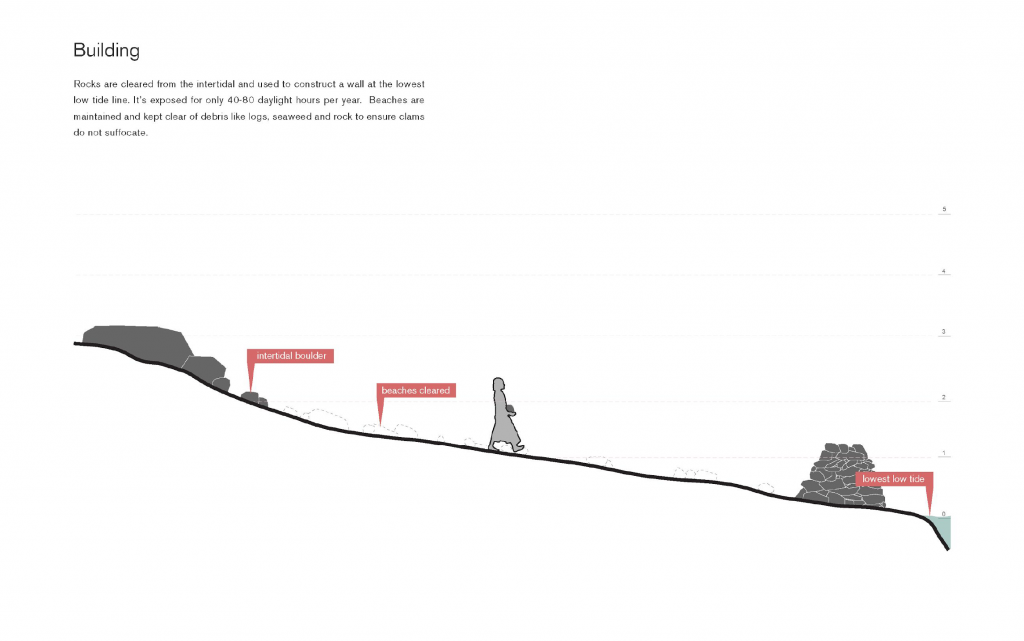

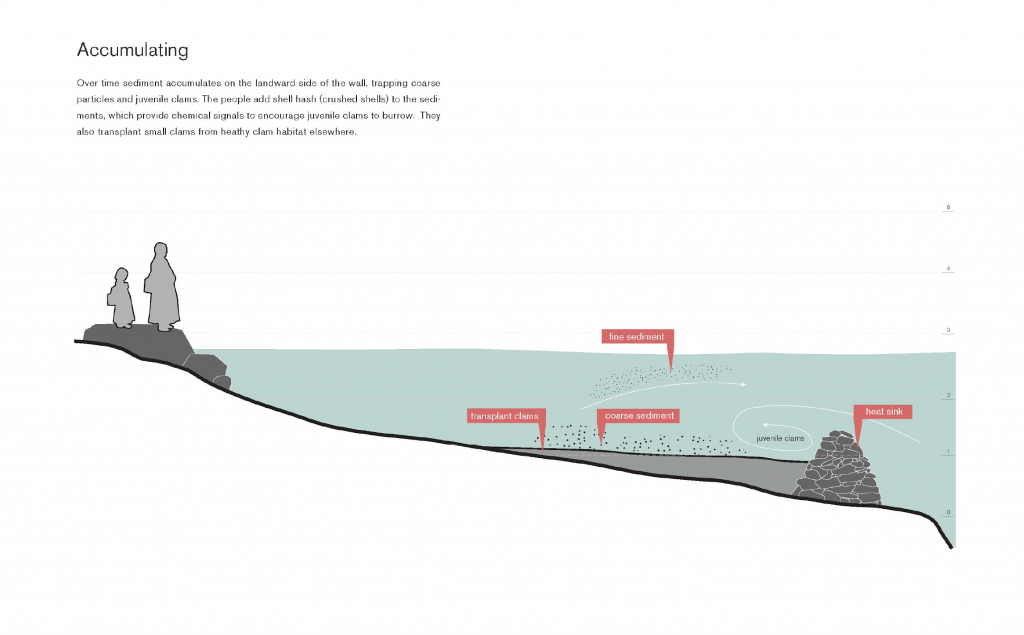

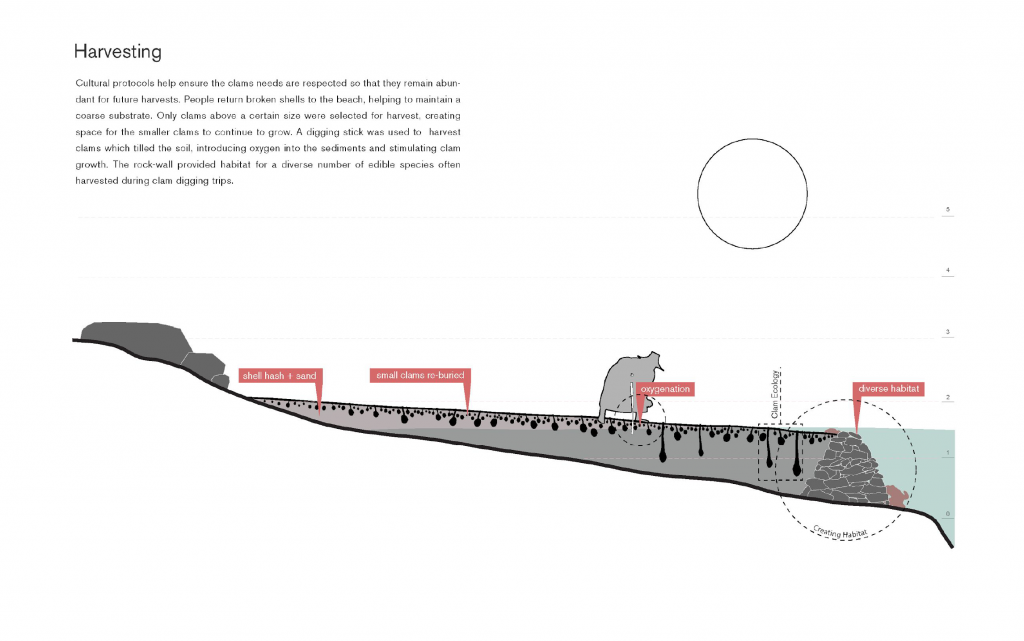

This ongoing research explores how Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest relate to, and co-design with, the dynamic living systems of abiotic, biotic and cultural processes of the coast. It specifically highlights the complex spatial and social-ecological systems associated with clam gardens: an ancient mariculture technique used by indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest.

Funding: Natural Resources Canada—Climate Change Adaptation Program

Research Assistants: Karen Tomkins, UBC School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture

We respectfully acknowledge that we live, work, and study on the unceded traditional territories of the Coast Salish peoples of the xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), Stó:lō, and Səl̓ílwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.