Paper Reviewed:

Solymosi, R., Bowers, K., & Fujiyama, T. (2015). Mapping fear of crime as a context-dependent everyday experience that varies in space and time. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 20, 193-211. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12084

When searching for a paper to review for my final presentation, I wanted to read more about volunteered geographic information (VGI) due to the in-class discussion on Participatory BioCitizen. I came across this paper on mapping fear of crime which conducted an interesting pilot study using a prototype mobile application to collect VGI. The results from this paper highlight that new insights into fear of crime could be attained by focusing on microscale geography with the additional dimension of time collected by their mobile application. The following is my review of the paper but I highly recommend reading the original paper as well, as I found the study (and the potential of ‘new’ technology to aid in data collection) to be incredibly engaging.

Fear of crime, which is far more than just fear of being a victim of crime, affects both those who have and those who have not been victimized. This makes fear of crime more prevalent than actual rates of victimization, and oftentimes the relationship between crime and fear of crime is not intuitive (Warr, 2000 as cited in Solymosi, Bowers, and Fujiyama, 2015, p. 193). For example, in the 2010-11 British Crime Survey, 43% of Londoners reported their quality of life was affected by fear of crime, and about 20% of Londoners claimed they had felt worried about their personal security in the last three months while traveling. As a result, fear of crime has knock-on effects on willingness to choose active travel modes, willingness to leave home unaccompanied, and on constraints to social behaviour by affecting overall quality of life and feelings of safety (Solymosi et al., 2015). However, fear of crime is mostly studied in relation to crime, or as an element of the environmental backcloth associated with crime (e.g., neighbourhood characteristics), and subsequently framed as rational or irrational in relation to actual (recorded) crime rates. The authors suggest that if fear of crime were to be addressed independently, i.e., treated as an independent event, it may lead to new insight into fear of crime research as demonstrated by the evolution of crime research. Hence, the purpose of their study is to highlight a need for innovation in research on the fear of crime to move on from general static representations and instead approach it as a dynamic phenomenon experienced in everyday life, to inform or evaluate situational interventions.

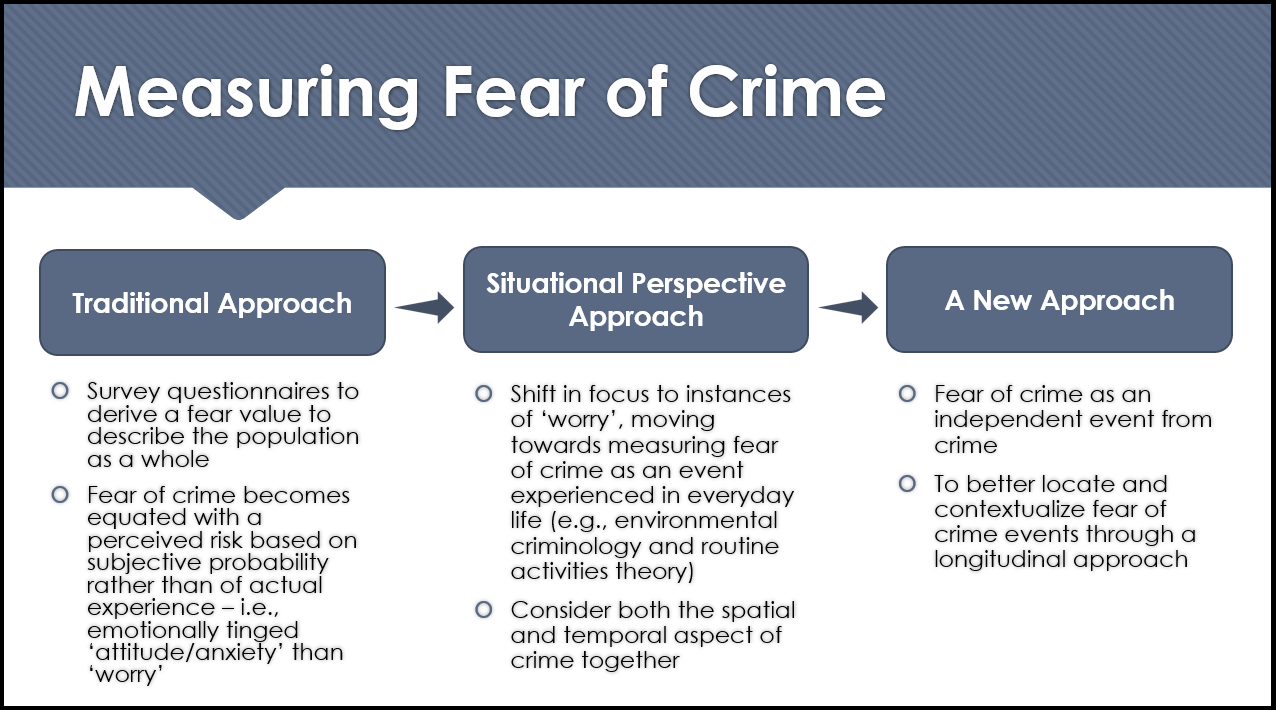

The traditional approach to measuring fear of crime has been to use survey questionnaires to derive a fear of crime value to describe the population as a whole, with any differences across subgroups analysed separately. However, when measured this way, fear of crime becomes equated with a perceived risk based on subjective probability, i.e., emotionally tinged ‘attitudes’, rather than a reflection of actual experience (Jackson, 2015 as cited in Solymosi et al., 2015). Therefore, the measure does not take into consideration variations in fear experience caused by perceived seriousness of crime and victimization. Questions about frequency and intensity, in the questionnaires, were only integrated in the last decade to measure instances of ‘worry’ rather than the ‘attitude’ of a more diffuse mental state; i.e., a movement towards measuring fear of crime as an event experienced in everyday life. The authors note that this shift in focus also led to the development of situational perspective (e.g., routine activity theory) to crime events by integrating spatial and temporal aspect of crime together in order to consider the larger system of activities which occur dependent on context. Nevertheless, even if experience-based questions move closer to capturing the more expressive dimensions of public insecurities (psychological reaction) about crime, results are not fully reflective of the dynamic way in which it is experienced by people over time as it still presents a static picture of something past (Solymosi et al., 2015). Therefore, it is important to consider fear of crime experiences from a longitudinal perspective in order to examine variation as people move through different spatial, temporal, and social contexts; where fear of crime is both transitory and situational. To do this, the authors propose a new approach that aims to measure fear of crime as it is experienced by people in the context of their everyday lives across the whole of their activity spaces, in real time, through the experience sampling method (ESM) with the crowdsourcing approach of volunteered geographical information (VGI).

The longitudinal approach of the ESM captures the representation of experience as it occurs, or close to its occurrence, within the context of a person’s everyday life. Furthermore, it provides a powerful way to understand psychological phenomena as they occur in daily life (Christensen & Barrett, 2003, as cited in Solymosi et al., 2015, p. 199). However, using ESM are more costly than traditional surveys and increases the burden on participants to complete the surveys at the appropriate time. To address these limitations, the authors applied this methodology via a mobile phone application. The use of mobile applications with sensors such as GPS and an internal clock allow for convenient collection of data (i.e., VGI), such as geographic location and time of response, which helps to reduce the burden on participants. Although VGI has underlying problems concerning the quality and accuracy of citizen volunteered data, such questions about data accuracy is assumed to be less relevant to subjective perception data by the authors. Moreover, to test the feasibility of using an application to measure fear of crime, a prototype was built through Java programming language for use on Android mobile devices. FOCA (i.e., the prototype) presented participants with an initial pre-experiment questionnaire with regards to fear of crime, and then ‘ping’ed participants periodically, asking them to answer pre-programmed questions. The application was later modified to include a retrospective annotation to avoid encouraging people to use valuable smartphones in high crime areas, and to allow participants to get to a safe place before reporting. This also meant that an additional question was added to allow participants to report how many hours ago the event took place, with a map of their current location to help (digitally) trace back their steps.

Six people (from a university setting) were asked to download and use FOCA for the duration of just over one month for the initial exploration of feasibility. Participants were ‘ping’ed up to four times a day at random times within each time slot (i.e., morning commute, daytime, evening commute, and night-time), for which was determined through stratified random sampling to represent times of movement more effectively. Initial results demonstrated intraperson variation in fear of crime, with specific instances when fear was reported, showing longitudinal within-person variation in fear of crime. Furthermore, by examining the spatial characteristics, the authors found that participants did not perceive an entire neighbourhood as safe or unsafe as a whole, but rather certain parts at certain times as safe, or less so; supporting the approach of fear of crime as a dynamic phenomenon. To determine the validity of (analysed) results, short interviews were conducted with participants. Overall, participants found FOCA easy and straightforward to use, with the map feature being a positive attribute to their reporting process. In addition, the authors found that participants related fear reports to a certain event, but not necessarily something that put the person themselves in direct danger, supporting the effect of psychological distance to crime affecting fear of crime. Therefore, results from this pilot did demonstrate spatio-temporal variation in individuals’ fear of crime levels, and thus the viability of VGI through the ESM approach.

Overall, the results of this study presented by the authors showed that new insights into fear of crime could be attained by focusing on microscale geography with the additional dimension of time as per their initial claim and study purpose. However, there are obvious limitations to the ESM approach and the mobile application due to lack of external validity, since only six people were sampled to participate in their feasibility analysis. Moreover, the mobile application (FOCA) is in prototype form which requires further development for future studies and possible usage. However, the authors did acknowledge these limitations, and recognized the need for an empirical study with data from a large enough sample to enable reliable data analysis. While the findings from this paper mainly show preliminary results from their small, trial of the FOCA mobile application, I think the authors have well-addressed their stated purpose of the study, especially through their extensive literature review, and have added value to approaches into fear of crime research. Therefore, I would rate this paper 9 out of 10 as it introduced a new approach to research on fear of crime by framing it as a context-dependent dynamic phenomenon experienced in everyday life, along with an interesting pilot study.