Paper Reviewed:

Rosero-Bixby, L. (2004). Spatial access to health care in Costa Rica and its equity: A GIS-based study. Social Science and Medicine, 58, 1271-1284. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00322-8

This author of this paper utilized one of the most common applications for GIS in health geography (i.e., modeling health services), but also integrated an econometrics component to the data analysis process which I found to be quite innovative. While this paper was quite heavy in statistics, it was still an interesting read regarding the Costa Rican health sector reform. As an economics student, being able to learn more about spatio-econometric analysis techniques is always a good opportunity.

Costa Rica has superlative health standards with life expectancy at birth being the second highest in the Americas while exceeding that of many countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health sector reforms that began in the 1990s have established universal, publicly-funded health care through the Costa Rican Social Security Fund (CCSS), removing administrative responsibilities from the Ministry of Health to instead focus on supervision and stewardship functions. In essence, the entire population has access to the health services of the CCSS as it is free of charge for the great majority of the population; and thus, prices are not considered a barrier to health care in Costa Rica (Rosero-Bixby, 2004). However, barriers exist in other forms: long waiting lists, perception of low quality of care, red tape, and the costs of traveling to clinics for users to receive services. While the reform was triggered by conditions such as limited resources to meet demand; inequities in the allocation of resources; poor quality of care; changes in the demographic and epidemiological profile of Costa Rica; and a shifting role of the State, it appears the dominant objectives in the process were of economic nature driven by loans from the World Bank (Rosero-Bixby, 2004). Yet, existing studies have mostly focused on the managerial, institutional, and regulatory achievements of the reform, rather than the reform impact on barriers to health care and triggers of the reform. Thus, in this paper the author aims to evaluate the impact of the ongoing Costa Rican health sector reform upon access to health care and its equity.

In public health, criteria of effectiveness and equity are paramount to conducting evaluations on provision of health care. This includes consideration for location of services and access by target population since it is an important determinant of costs for users. While the concept of accessibility to health care has at least two dimensions: physical (or geographic) and social, the author focused on physical accessibility to evaluate equity in access to health care. Physical accessibility is defined through traditional measurements of access that is based on the distance (or travel time) to the nearest facility, as well as through a more comprehensive index of accessibility that results from the aggregation of all facilities weighted by their proximity, size, and characteristics of both the population and the facility. The latter measure is used to address peculiarities demonstrated by users, such as the failure to use the nearest facility, and to be free of restrictions inherent to arbitrary geographic units defined for political and administrative purposes.

Furthermore, demand for health services (i.e., population) from the geocoded 2000 census was combined with data on supply from a geocoded inventory of health facilities; where the confluence of supply and demand resulted in the concept of accessibility. However, knowledge of supply, unlike demand, was found to be limited in existing records and studies due to discrepancy between administrative data about the supply of services and reality. Therefore, an exhaustive list of all facilities mentioned in statistical and administrative reports were compiled, updated with information on the ranges of services offered (e.g., primary care, surgery, and so on) and facility’s size, and geocoded by recording appropriate coordinates on the map. This was followed by a telephone survey to health officers in central and regional offices to clean inventory data and to gather missing information on a small number of key variables, along with field visits to a sample of 40 randomly selected facilities to validate the inventory. Moreover, information on area boundaries and specific sectors covered by the health sector reform over time was provided by the CCSS. Given that the reforms were not introduced at the same time everywhere, areas were classified into three groups according to the year they joined the reform: (1) pioneers; (2) intermediate; and (3) laggards. This data on supply was subsequently designed to account for the natural quasi-experiment that occurred in Costa Rica to be able to assess the effect of the reform on access to health care.

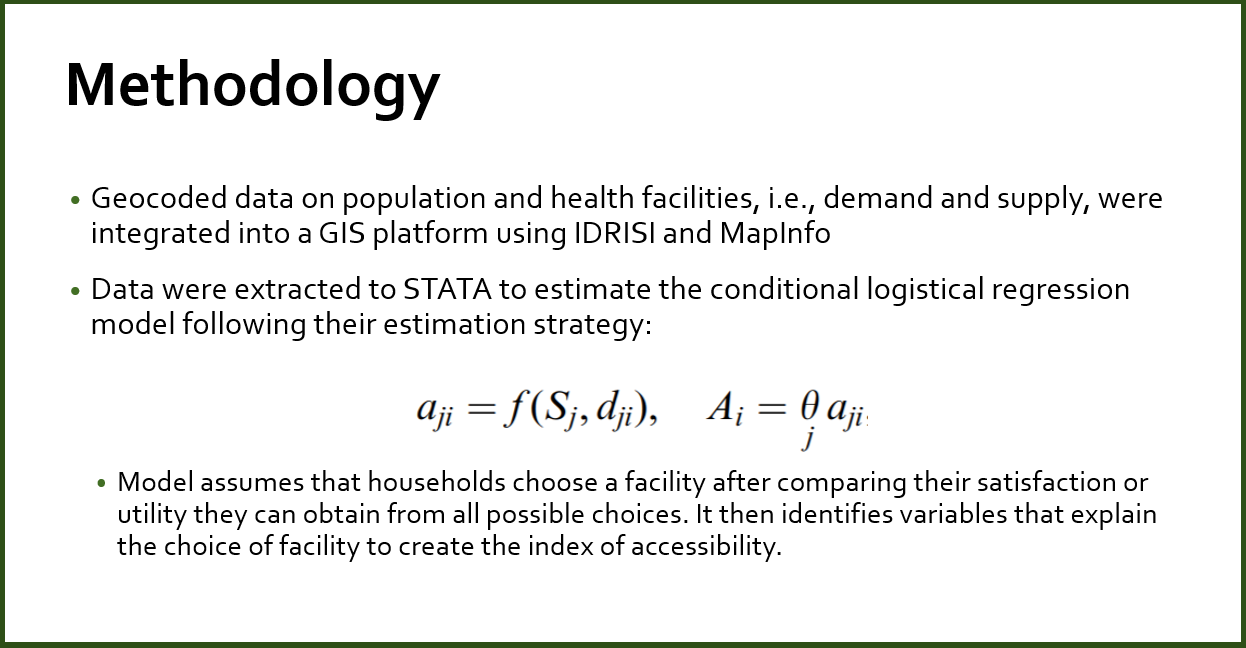

Geocoded data on population and health facilities, with administrative division of Costa Rica at three levels (provinces, cantons and districts), the health areas in the reform of the health sector, highways and other characteristics, were integrated to a GIS using IDRISI and MapInfo. This allowed for visualization of accessibility of health services by overlaying the supply and demand layers in GIS. The quantification of indicators to operationalize the concept of accessibility was measured by: (1) a general definition of accessibility to each facility (for an individual i to a facility j) as a function of distance and utility derived from the service; and (2) an aggregate of accessibility to each facility into a summary index of accessibility to all facilities. Then, conditional logistical regression was used to model the probability of selection of a health facility in the database. The model is based on the assumption that households choose a facility after comparing obtainable utility from all possible choices. From this the model identifies variables that explain the choice of facility to construct the index of accessibility. Moreover, in order to determine the impact of reform on equity of access, (somewhat) arbitrary cut-off points (i.e., 4 km for a facility offering outpatient services, 25 km to a hospital, and 0.2 yearly MD hours per capita) were set as threshold of access to use as an indicator of inequity or unmet need.

Estimates from the conditional logistical regression model and the descriptive statistics of health facilities, population characteristics and services by timing of reform from STATA, using the integrated demand and supply data from a GIS platform, showed that half of Costa Ricans reside less than 1 km away from an outpatient care outlet and 5 km away from a hospital. In equity terms, 12–14% of population were found to be underserved, according to the 3 indicators of access (i.e., closest outpatient care, closest hospital care, and density of health care facilities). Furthermore, pioneering areas, where reform began in 1995-96, experienced inequitable decline in access to outpatient health care from 30% to 22%, whereas in areas where reform has not yet occurred experienced a slight increase from 7% to 9%. Considering that the reform of the health sector in Costa Rica began in outlying areas characterized by disperse population, low socioeconomic levels, and poor access to health services, the reform has narrowed the gap of inequitable access. However, the “friction of distance” was still found to be larger in rural areas, contributing to the costs for users to access health care services.

The econometric analysis in STATA in conjunction with the integration of demand and supply data in a GIS platform was a fairly innovative technique to address limitations from previous studies, such as the peculiarities demonstrated by service users, restrictions inherent to arbitrary geographic restrictions, and discrepancy between administrative data and reality. Moreover, this study emphasized the need to centrally organize a complete, but simple, information system on the supply of health services due to the immense trouble the author underwent to develop a suitable dataset. Recognizing that the supply and demand of health services is critically important in understanding the concept of accessibility of health services for the population in addition to monitoring and evaluating the impact of current reforms in the health sector, I find it difficult to become fully convinced by the findings in this paper for this exact reason. While the author was resourceful in developing data for supply, there is lack of assurance that the data is fully accurate, and free of sampling error and of systematic bias. So, there is a chance that the results may change depending on the data used to measure supply, even though the estimation strategy for the conditional logistical regression model for access indicators is sound. As a result, I would rate this paper 8 out of 10 considering the remaining uncertainties with the data.