One of the issues that we have encountered during the first week of baseline is that some of the houses that were originally selected to be part of the study are no longer eligible.

In some instances, the mother went to Phnom Penh or the Thai border to seek work. The purpose of our study is to show the effects of HFP and aquaculture on household food security and the nutritional status of women and children. As such, the woman of the house must be present year-round to reap the benefits of these interventions. By migrating for work, a woman’s nutritional status at the end of the study would not reflect the addition of HFP and aquaculture in her life. Therefore, her household is now ineligible for participation in FoF.

In other instances, when we arrived at the house we found out that the children were over the cutoff age of 5 years old. This happened for a variety of reasons: some women couldn’t accurately remember the date of birth (the Khmer calendar is different from ours), the selection team didn’t check the proper documents to verify the child’s age, or the age on the village chief’s list was incorrect. It’s also possible that some women provided false ages for their children because they wanted to be part of a study that provides the expensive inputs needed for HFP and aquaculture.

In any event, our team has been scrambling to fill their spots so that we have the right sample size for the study. We’ve accounted for a possible 15% of houses lost due to follow up, but we want to start with the biggest sample possible to minimize that loss given how expensive and time-consuming the project is.

This seems like a good opportunity to discuss the methodology behind household selection. In an earlier post (Household Selection), I briefly outlined the criteria that households needed to meet to be part of FoF. However, meeting the selection criteria does not mean a household is automatically enrolled in FoF. This is, after all, a scientific experiment; certain research principles must be upheld.

In order for this to be a valid and reliable scientific experiment, we need our sample to represent our target population as closely as possible while eliminating any potential biases or confounders. We achieve this by picking the proper sampling method. FoF is using a multi-stage sampling strategy. The first stage is cluster sampling, which is a form of probability sampling that examines naturally occurring groups such as villages. The second stage is systematic sampling, which is used to select the houses in the villages by picking a random point to start (eg the fourth house on the list) and continuing through the list in a systematic fashion (eg every fourth house on the list). A few key definitions are needed at this point:

- Valid – we are measuring what we say we are going to measure

- Reliable – our measurements are as accurate as possible

- Probability sampling – the entire target population is known, and thus everyone in that population has an equal chance of being selected

- Randomization – picking units (in our case, villages) at random to ensure the sample is representative of the target population

- Target Population – the population we want to study, as defined by certain parameters (eg location, age, SES)

First, we looked at all of the villages in the province of Prey Veng on a list from the most recent census conducted by the Ministry of Planning in 2008. We excluded the villages that had already been part of a HFP program by HKI that was funded by the EU, the villages that are part of the ongoing ODOV (Organization for Development of Our Villages – one of our partner NGOs) food security project, and the villages that are taking part in other Cambodian NGO projects. This left us with 164 villages in 4 districts: Ba Phnum, Kamchay Mear, Me Sung, and Svay Antor. Then the villages were randomized, resulting in 120 villages with 40 villages per group (HFP, HFP + aquaculture, or comparison) being selected. Finally, 30 out of 40 villages were selected after further randomization.

Workers from the ODOV went into the field and met with the village chiefs (and in some instances, a village council) to divide the households with children under the age of five into 3 categories: poorest, poor, and medium wealth. They wrote their wealth ranking assessment for each household on a slip of paper that was placed into a box to maintain anonymity. This was done because it was our intention to try to help those most in need.

The ODOV and the village chiefs met with the households categorized as poorest or poor to explain the project to them and to ask if they were interested in joining. If they responded “yes”, field staff went to the house to make sure it met the selection criteria. They made sure that each house had enough land to support HFP farms and fish ponds, and they assessed whether or not the house would be able to maintain these projects during the course of our study. They also inquired about the ages of the children, most often by looking at the village chief’s list of villagers, but as we’ve discovered this list isn’t always correct.

A list of all eligible households was sent back to HKI. The houses categorized as poor or poorest were listed, and from that list we began with the 4th house and picked every 4th house after that. We were able to find 10 eligible houses in each village by using this method. The ODOV received a list of selected households and went to the village chief to inform him of the date and time of the survey.

In the field, each supervisor brings his or her list of 10 households per village that have been selected for the study. Sometimes, something goes amiss and the household is no longer eligible (for all of the reasons I listed above). Then we have 2 options: 1, we pick another house categorized as poor on the ODOV list that wasn’t originally selected during the systematic sampling; or 2, we go back to the very first list that the ODOV produced (the one that listed all the households in the village before the wealth ranking) and we discuss with the chief whether or not picking a new house from that list is a good idea. This means that sometimes we will get houses that vary in socioeconomic status (SES). Ideally, we’d like to control for SES before we collect data, but our survey includes a module about household income and wealth that will allow us to control for SES after the data has been collected.

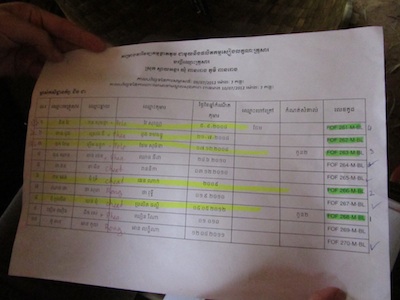

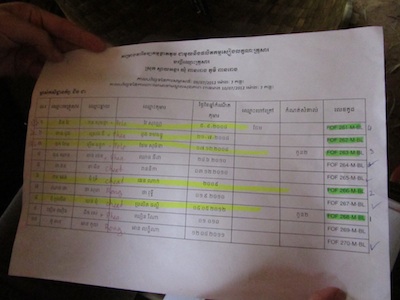

Once we have our 10 houses picked in the village, we hold a lottery to randomly select 5 houses to participate in the 24-hour recall and blood analysis components of our study. Slips of paper with the numbers 1 through 10 are placed faced down, and 5 slips are drawn. Those houses are highlighted on the list. If, for some reason, we have to replace a house that has been highlighted, the replacement house is automatically assigned to be part of the 24-hour recall and blood draw. The enumerator goes to the house to conduct the 24-hour recall and to obtain consent (very important) for the blood draw. The woman is given a slip of paper that has her unique identifier and the time and location of the blood draw. We are only conducting recalls and collecting samples from 450 women (half of the women in the study) because the recalls are time-consuming and the blood collection is invasive and expensive.

Households selected by lottery for the 24-hour recall and blood draw

And that is the method we used to recruit 900 households for FoF while adhering to the principles of sound research as best as we possibly can.

I’d like to give a special thank you to Sokhoing Ly from HKI for explaining all of this to me with great patience.